Monday, March 21: The Scribbler

MODERATION IN ALL THINGS

by James Lincoln Warren

It looks like I’m the only member of the CB crew who will be heading off to Malice Domestic in Bethesda, Maryland, at the end of next month. For those of you unfamiliar with this particular fan convention, it is dedicated to the “traditional mystery,” and its patron saint is Agatha Christie. After Bouchercon, it’s the biggest and most prestigious of all the various gatherings in mystery fiction fandom, and unlike Bouchercon, it really is mostly about the fans rather than the writers.

Their awards, the “Agathas,” take the form of ceramic teapots and are much coveted by scribblers, since winning an Agatha almost always guarantees that a book will reach its intended audience, thus turning into extra printings. Malice is also probably the most congenial of all mystery conventions—Jan Burke calls it “the world’s largest family reunion.” I always have a great time there, but having given it a miss for the last several years—I usually combine it with a trip to New York for the Edgar Banquet, which immediately precedes it—I’m very much looking forward to it.

I’ve been assigned as the moderator for a panel on Saturday morning called “Better Together: Amateur Sleuths Who Work with the Police”. Assignments to panels are always mysterious, and I found this one a wee bit curious because I’ve only written one story featuring an amateur sleuth, and she lived at a time when there were no police around to work with. But I’m always happy to get an assignment no matter what it is, and by the time the convention rolls around, I will be well prepared to draw out the various insights of the panel members: Jane Cleland, P. L. Gaus, B. K. Stevens, and Leann Sweeney. (By the way, Bonnie Stevens’ new story is in the same issue of AHMM as Rob Lopresti’s story “Why”, which I discussed two weeks ago. Recommended.)

Not that I intend to bring it up, but I have always found amateur sleuths, with some rare exceptions, to be problematical, and that’s why my detectives are always pros—even my amateur, Mrs. Stavacre, was employed to determine cause of death, and so had a reason for being near corpses. Think about it. Sleepy little Cabot Cove must have been the murder capital of the world, and being related to one of Jessica Fletcher’s friends was tantamount to a death warrant or a long prison term. Most of us do not stumble upon murders very often, and even if that horrific crime does impinge on lives, it doesn’t present itself as a problem to be solved as much as it does as a numbing and debilitating shock.

Combining an amateur with a policeman at least provides a cover for the amateur, although it may not always explain why the professional puts up with the interference of a nosy civilian, which if you think about it is somewhat ghoulish—criminals are well known to inject themselves in investigations, after all, so the civilian’s presence in real life would definitely raise some eyebrows. But let’s not be harsh or overbearing, because the amateur detective is every bit as conventional a sleuth as any hard-boiled private dick, and frankly, not a bit less realistic. Jon Breen’s wonderful detectives are mostly amateurs. Miss Marple, the ur-amateur, is my third favorite detective in all of crime fiction, after Holmes and Marlowe.

My fourth favorite detective, though, definitely fits the bill of an amateur who hangs out with the police. That’s Lord Peter Wimsey, in case you were wondering. His presence is a little easier to explain than most amateurs, at least most of the time. First of all, rather than be at the right place at the wrong time and stumbling over the body in the hallway, although similar coincidences certainly do occur in Sayers’ oeuvre, Lord Peter is usually asked to investigate by someone in trouble who needs his help. At first, his presence at crime scenes, etc., is tolerated by virtue of the British class system, since he is the second son of a Duke and has the ear of many a distinguished personage in Government—and in one story, even the ear of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Later, of course, he is tolerated because Inspector Parker is his brother in law.

But readers do not tolerate amateurs because of any such niceties. Rather, readers like amateurs because they feel affection for them. We love Miss Marple, old cynic that she is. We love Wimsey’s wit and warmth. But I think that we mostly love amateurs because they pursue investigations not because it is their job and duty, but purely for the sake of seeing justice served. This is an appealing and admirable characteristic. Despite whatever faults the amateur may have, this is a redeeming strength. The reader, after all, is almost always an amateur, too, even if the writer is a professional law enforcement officer in real life. To a certain extent, we all like to read about ourselves.

So not for the Malice crowd the dark despondent corners of noir or the seedy underbelly of twisted psychopathological obsession. Good, clean justice, that’s the ticket, where the wicked shall cease from troubling and the weary be at rest. And that’s fine with me.

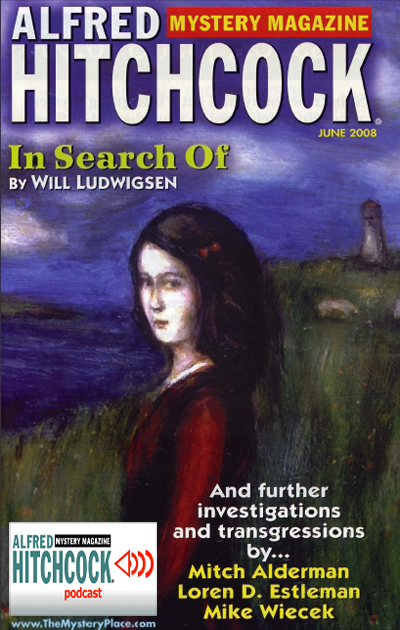

In Search Of

In Search Of I grew up watching the

I grew up watching the  I’ve never found Nancy C. Swoboda but I owe her a great debt. It was her story that rang my mental bells so precisely that it occurred to me that people wrote these things on purpose, mostly for other weirdoes like themselves. It awakened me to the possibilities of writing about the things I loved, not the boring literary stuff we had to read in school.

I’ve never found Nancy C. Swoboda but I owe her a great debt. It was her story that rang my mental bells so precisely that it occurred to me that people wrote these things on purpose, mostly for other weirdoes like themselves. It awakened me to the possibilities of writing about the things I loved, not the boring literary stuff we had to read in school.