Monday, February 14: Spirit of the Law

Before introducing today’s column, I’d like to call your attention to a new feature of the website, Petition the Court, at right in the Sidebar. Leigh pointed out to all of us that it’s been some time since the regular contributors all joined in a common project or thread. After a lot of discussion, we decided that we would ask you, our readers, if there are any topics you would like all (eight) of us to tackle over the period of a week. Petition the Court is the means to do this. Click on the link and you will be redirected to a webpage email form where you can suggest topics you’d like to see us address. The generated email will be simultaneously sent to all of us for our consideration.

Now back to our regularly scheduled blog.

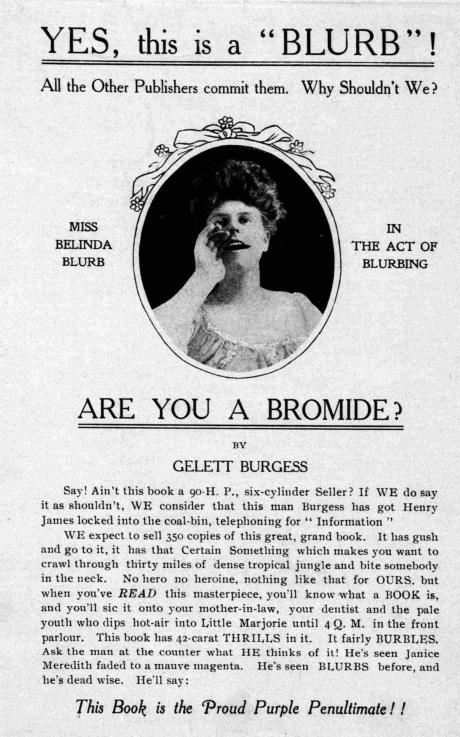

As a St. Valentine’s Day gift to the Gentle Reader, I am pleased to announce that we’ve added another regular columnist to our line up. Henceforward, Janice Law will be alternating columns with me on Mondays. Those of you who read Alfred Hitchcock and Ellery Queen are no doubt already familiar with her excellent short stories; others may be familiar with her critically acclaimed Anna Peters series of mystery novels. When I asked her to blurb (sorry about that, Steve) her accomplishments for this introduction, she modestly wrote:

“Janice Law’s short stories frequently appear in AHMM and EQMM. Her collection of her earlier stories, Blood in the Water and Other Secrets, has just been released by Wildside Press.”

Please welcome Janice and our new column, Spirit of the Law (with apologies to Montesquieu!).

—JLW

FRIENDS AND ACQUAINTANCES

by Janice Law

I’ve just had the interesting experience of readying a collection of my earlier short stories for print, and as a novelist who writes short stories, rather than a short story writer who writes novels, I’ve been wondering about the differences in the characters of each genre.

I’ve concluded that while, with few exceptions, characters in novels are friends, short story protagonists are acquaintances, and none the worse for that. Think about it: if you write a novel, you’re going to be living with the main characters for nine months or so (unless you’re Georges Simenon) and maybe much longer. Better love them, and better hope that they are people who grow and keep growing as long as you need them. If not, you’re in for some very long days at the writing desk.

The inhabitants of one’s short stories are a different matter. Like Jane Austen’s lovers, who are ushered off stage as soon as they are married, the protagonists of short mystery fiction need only to hang around until they are dead, caught, or triumphant. Usually one of those options overtakes them within 15 pages, and one need never worry about them again.

Of course, one can speculate. Were the young couple in my Bluebeard story, “The Paradise Garden,” destined for happiness? I don’t know, but I’m hopeful for them. On the other hand, the lucky young woman in “The Helpful Stranger” may find her new life no more satisfactory than her old. Do I know for sure? No way. They have not confided in me any further.

But if our relationship has definite parameters, it is not necessarily superficial. I know a lot about the obsessive producer of “Perfection” and I don’t necessarily want to know more. I find him, frankly, unsympathetic, although like all of my characters he represents some facet of my personality. Lets face it, some people we just don’t want to spend a lot of time with.

And yet, for the mystery writer, long form or short, these are just the folks essential to our business. The solution, sometimes, is to go short. I constructed a psychopathic college student once, whom I didn’t like at all, but who enlivened a story called “Lying” immensely. A whole novel with Bren would have strained my good nature. But in 14 pages or so with a different narrator, I’d have to say she fit the bill.

Of course, as in this case, one needn’t use a disagreeable person as narrator, although that can be very effective. Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine recently ran a story called “The Writing Workshop,” which contains good and standard advice on writing, although the instructor is not all he might be.

In general, though, I prefer to approach evil at an angle, and while my stories are about crimes, rather than detection, bad things often happen just a little to one side. What really interests me is not the mechanics of crime—the spatter of blood, the caliber of weapon, or even the logic of the investigator—but the great narrative questions of why did something happen and what were the consequences.

For this reason I have indulged in a wide variety of characters, male and female, young and old, rich, poor, educated or not, and matched them up with a fair range of homicides. The latter come straight from that great friend of the crime novelist, the press. The means are a given, usually, and my job is to come up with characters who will bring the story to life.

They rarely resemble their actual prototypes, and I find that one only needs a certain amount of information. Too much and the Muse gets swamped by reality. Sometimes, too, it takes a good long time for the story to come together. Ellery Queen ran a story of mine last year called “The City of Radiant Brides” based loosely on a multiple shooting at a Connecticut garage.

I’d cut the story out immediately. Then it sat in my notebook for several years while I considered the right point of view and cast about for the right character: Shooter? Victim? Mobster behind the hit? Nothing worked until I focused on the woman in the case. And she didn’t work, either, until I realized that she was a thwarted romantic longing for the City of Radiant Brides, AKA the celebrity world of TV, tabloids, and the net. Then the story pretty much wrote itself.

Could I have done a whole novel with her? I don’t think so. Her obsession with the princes and princesses of pop culture was fun for a couple of pages but would have proved a strain at length, celebrity websites and People Magazine not being my particular guilty pleasure. A whole book about her would have turned into work and not particularly congenial work.

I enjoyed her while I wrote the story. She was fun to know and she surprised me at least once, the sign of a good character. But she was an acquaintance, not a friend, and I haven’t the faintest idea of what became of her after she walked out of the story.