Monday, June 21: The Scribbler

THE SEVEN PER CENT SOLUTION

by James Lincoln Warren

Sherlock Holmes took his bottle from the corner of the mantel-piece and his hypodermic syringe from its neat morocco case. With his long, white, nervous fingers he adjusted the delicate needle, and rolled back his left shirt-cuff. For some little time his eyes rested thoughtfully upon the sinewy forearm and wrist all dotted and scarred with innumerable puncture-marks. Finally he thrust the sharp point home, pressed down the tiny piston, and sank back into the velvet-lined arm-chair with a long sigh of satisfaction.

“Which is it to-day?” I asked,—“morphine or cocaine?”

He raised his eyes languidly from the old black-letter volume which he had opened. “It is cocaine,” he said,—”a seven-per-cent. solution. Would you care to try it?”

—Arthur Conan Doyle, The Sign of the Four

Whenever I encounter the phrase “seven per cent,” the first thing that leaps to my mind is Sherlock Holmes’ preferred remedy for escaping ennui and clearing his brain. It is a fact that cocaine and its analogs have a direct effect on the physiology of the brain and temporarily enhance rapidity of thought.1

Cocaine does not make you smart, though, anymore than boozing up makes you better looking, although I have observed that many people act as though they were convinced it does, especially at late night parties. In the long run, the seven per cent solution doesn’t work.

So the Gentle Reader may forgive me when I say that I am not at all convinced that words comprise only seven per cent of communication, although such is the current received wisdom. Usually this nugget is expressed something like this:

One study at UCLA indicated that up to 93 percent of communication effectiveness is determined by nonverbal cues. Another study indicated that the impact of a performance was determined 7 percent by the words used, 38 percent by voice quality, and 55 percent by the nonverbal communication.2

The first thing that strikes me about this quote is that if 93% of communication is nonverbal, then what’s left, i.e., 7%, must necessarily be verbal. The unidentified “other” study merely regurgitates that same figure, dividing up the nonverbal portion into separate categories. But I have questions.

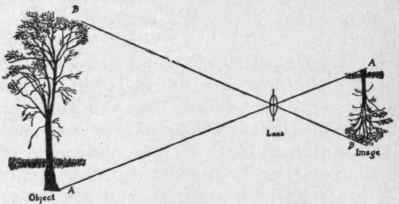

What study at UCLA? When was it done, and by whom?3 How did the people conducting it quantitatively measure “communication effectiveness”? What exactly was being communicated? As I have written before, communication requires both a transmitter and a receiver, and its “effectiveness” depends on how well they both work on their own and how well they work together—and on the nature of the data being pushed across the divide.

Ever try giving directions to someone who doesn’t speak the same language as you? Of course there’s a nonverbal component in providing such an explanation, but it’s a hell of a lot easier if you can say, “Take your third left and then the second right,” with a reasonable expectation that your words will be understood than if you’re stuck relying on pantomime to convey your instructions.

On the other hand, threaten somebody with a claw hammer and words become pretty much superfluous. The words one uses when talking to a baby or a dog are certainly less important than their tone—but infants and pets aren’t constitutionally capable of communicating abstract ideas in the first place. (I make an exception of Valentine, Leigh’s avian companion.)

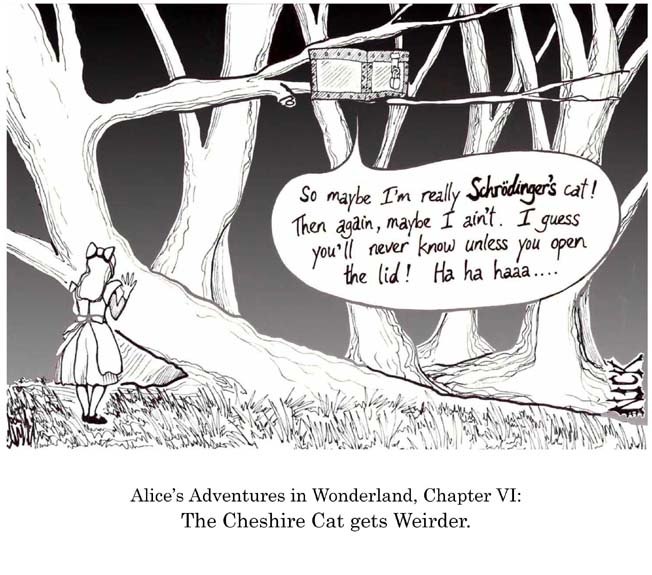

What I think is that the simplistic notion that nonverbal means convey more information than verbal ones completely misses the point. Words by their very nature are associative. A word, after all, is not the same thing that it represents.4 That means that words’ full meanings are dependent on context. This should surprise no one. The word “awesome” coming out of the mouth of a fashion-conscious girl admiring a pair of shoes does not mean the same thing as it does coming out of the mouth of an astronomer transfixed by the majesty of the cosmos. The context colors the diction. I freely admit that such contexts are frequently, maybe even most of the time, largely “nonverbal”—but not always.

Good verbal skills build contexts, or at least demand that the reader (or listener) engage his imagination to fill in the blanks. (I frequently call this “making the reader do the work.”) One way to get somebody’s attention is to present a scene devoid of context, forcing the reader to ask, “What’s going on here?” The true meaning of the scene only becomes clear when the context is subsequently filled in. This is a very common technique in story-telling, especially in mysteries. It’s why the Iliad begins with the wrath of Achilles, why crime shows so frequently begin with the discovery of an unidentified victim, why so many stories begin with a sliver of dialogue that teases the reader into asking what’s being talked about. Getting somebody’s attention is also a form of communicating.

And that’s exactly what separates a great story teller from a pedestrian one. By engaging one’s imagination, the good story teller enables the reader to build an entire world of context in his own head. The application of words alone breathe life into a tale.

Not to claim such a distinction for my own work, but the comments that most please me from readers are when somebody particularly enjoys a key characteristic of a tale—for the historicals, it’s the belief that one can sense what London was really like in 1776; for the hard-boileds, it’s the defining snappy dialogue; for my soon-to-be published woo-woo5, it’s the brooding and scary atmosphere. Place, character, and mood. All matters of context.

It’s always nice to be complimented on a clever plot or an engaging storyline. But the best praise comes when one has communicated so well that the words on the page transport the reader into a new world. Of course, that’s what some crazy folks claim for cocaine.

- Nicotine, for example, has been definitively shown to stimulate the brain and increase concentration for short periods of time—that’s why some people light up a cigarette when they are trying to think. Cf. Holmes’ own tobacco abuse:

“As a rule,” said Holmes, “the more bizarre a thing is the less mysterious it proves to be. It is your commonplace, featureless crimes which are really puzzling, just as a commonplace face is the most difficult to identify. But I must be prompt over this matter.”

“What are you going to do, then?” I asked.

“To smoke,” he answered. “It is quite a three pipe problem, and I beg that you won’t speak to me for fifty minutes.” He curled himself up in his chair, with his thin knees drawn up to his hawk-like nose, and there he sat with his eyes closed and his black clay pipe thrusting out like the bill of some strange bird.

—Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Red-Headed League”

[↩]

- “Listen With Your Eyes: Tips for Understanding Nonverbal Communication,” by Susan M. Heathfield. [↩]

- After digging a little, I found out that the referenced study was done by UCLA psychology professor Albert Mehrabian in 1967, and that as I suspected, there weren’t two studies, but only one—Mehrabian got two papers out of it, “Decoding of Inconsistent Communications” in The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology and “Inference of Attitudes from Nonverbal Communication in Two Channels” in The Journal of Consulting Psychology. Mehrabian also provided this caveat: “Please note that this and other equations regarding relative importance of verbal and nonverbal messages were derived from experiments dealing with communications of feelings and attitudes (i.e., like-dislike). Unless a communicator is talking about their feelings or attitudes, these equations are not applicable.” [↩]

- Gertrude Stein’s famous witticism, “A rose is a rose is a rose,” is correctly interpreted to mean that the expression “a rose is a rose” is representatively a “rose” itself, i.e., a flower of speech; and not the more prosaic and common notion that a that which we call rose is an actual rose and not anything but such a rose. It’s a perfect example of context determining semantic content. [↩]

- See the trailer here if you haven’t already—I had a lot of fun making it, although I must confess that it relies heavily on, ahem, nonverbal communication. [↩]