Saturday, July 5: Mississippi Mud

MAP QUEST

by John M. Floyd

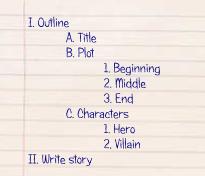

One of the questions I’m often asked at book signings (it ranks just below “Where do you get your ideas?” and “Can you point me to the section on nonfiction?”) is: “Do you outline your stories before you start writing?”

It’s an easy question to answer, but I always feel I need to qualify it a bit.

A Split Decision

Everybody seems to have a different take on outlining. Something that I’ve found surprising as a writing instructor is that almost exactly half of each of my classes say they always outline, and have a pretty definite idea of the entire storyline before they begin. The other half say they never outline — they start with a blank page and no plan and see where the writing takes them. Author James Scott Bell once referred to the first group as OPs (Outline People) and the others as No-OPs.

Everybody seems to have a different take on outlining. Something that I’ve found surprising as a writing instructor is that almost exactly half of each of my classes say they always outline, and have a pretty definite idea of the entire storyline before they begin. The other half say they never outline — they start with a blank page and no plan and see where the writing takes them. Author James Scott Bell once referred to the first group as OPs (Outline People) and the others as No-OPs.

The real question, though, is not “Do you?” It’s “Should you?” And it’s one of those rare questions that doesn’t have a right or wrong answer. It all depends on the person. I think we’re just wired differently when it comes to this issue, and what works for one writer won’t work for another. In fact I think the do-you-or-don’t-you-outline answer can be dangerous — or at least misleading — if it’s given by a professional writer (in a classroom, for example) to a fledgling writer. I once heard that a poor teacher is one who says, on any subject, “This is the way you do it,” and a good teacher is one who says, “This is the way I do it.” I don’t think I should try to change an aspiring writer’s mind about outlining, any more than I should try to change his “voice” in telling a story.

Confessions of an OP

Personally, I do outline my stories, or at least (for short stories) map them out in my head, before I start writing. And I don’t do it because I think it’s the right thing to do; I do it because it’s the only way I can write. Other authors have told me they never ever outline, in any form, because if they did it would keep them from writing, or at least writing well. And I believe them. Different strokes, right?

Personally, I do outline my stories, or at least (for short stories) map them out in my head, before I start writing. And I don’t do it because I think it’s the right thing to do; I do it because it’s the only way I can write. Other authors have told me they never ever outline, in any form, because if they did it would keep them from writing, or at least writing well. And I believe them. Different strokes, right?

Some of the people who’ve heard my own preference nod wisely and say, “I bet you outline because of your engineering background. You’re probably well organized in other things that you do, so you’re organized in the way you write.” Well, I’m not sure I buy that. For one thing, I’m not all that organized in the other things that I do. I’m not even sure I would like being organized. Again, the reason I plan out my stories beforehand is that I couldn’t write them if I didn’t. I simply cannot start putting words on paper if I don’t first have a fairly good idea where the story’s going.

Flexibility

The operative word, in that previous sentence, is “fairly.” I’m never totally certain how a story will end up, because after the process starts, the storyline almost always changes direction a bit, and that’s usually for the best. But even if it does change, I still have to have some kind of ending in my mind before I start. That part, to me, is like real life, because I also have to know my destination before I climb into the car and pull out of the driveway. If I didn’t, there’s no telling where I might end up, or how long it might take me to get there. (My days of just driving around for fun, as I once did in our younger son’s topless Jeep, are over, at least until gas prices go down a little.)

1 I even suspect that experienced writers who swear that they don’t outline (among them Stephen King, Elmore Leonard, etc.) actually do have at least a rough idea of where things are going before the writing starts. I read someplace that if an architect has built a hundred houses, he can be expected to build number 101 without having to refer to a blueprint. It’s the same with authors — you get better at this the more you do it. A seasoned writer might say he’s flying by the seat of his pants, but a general structure of sorts might be there in his head during the whole process. It’s just become so second-nature to him, he’s not even conscious of it.

1 I even suspect that experienced writers who swear that they don’t outline (among them Stephen King, Elmore Leonard, etc.) actually do have at least a rough idea of where things are going before the writing starts. I read someplace that if an architect has built a hundred houses, he can be expected to build number 101 without having to refer to a blueprint. It’s the same with authors — you get better at this the more you do it. A seasoned writer might say he’s flying by the seat of his pants, but a general structure of sorts might be there in his head during the whole process. It’s just become so second-nature to him, he’s not even conscious of it.

(Again, I’m not necessarily talking about long, detailed, written outlines. For short stories, the “plan” might just be a vague map in my head, of how the story will end and how it’ll progress toward that ending. I think that kind of mental plotting is a lot of fun, and, for me at least, usually takes up more time than the actual writing of the story.)

A Few Pros and Cons

On the OP side:

- Elizabeth Lyon says, in A Writer’s Guide to Fiction: “Whether you’re writing short stories or novels, you’re more likely to start — and finish — if you have a plan. Fiction writers need outlines. The payoff for learning how to map your stories is saving time — perhaps years of rejections — lost by ‘free’ writing.”

- Noah Lukeman says an outline (and even a preconceived ending) is a good thing, but doesn’t have to be set in stone: “It is like putting your character on a train bound for California. If he decides to get off in Arizona, that’s fine. If it turns out he should settle there and never get back on the train, that’s fine too. But he could never have known about Arizona if he hadn’t first gotten on that train for California — if he hadn’t had some destination in mind.”

- Loren Estleman: “A writer needs to know where he or she is going before the writing begins.”

- Tony Hillerman: “You don’t have to outline a plot if you have a reasonably long life expectancy.” (The funny thing, here, is that Hillerman usually doesn’t outline.)

On the No-OP side of the argument:

- Joe Gores says that outlining would stifle his effectiveness: “The hero’s search for a way out of his dilemma is best created by the writer putting himself in that same dilemma.”

- Lawrence Block once made a similar observation, which he attributed to Thomas Spurgeon: if he didn’t know who the killer was as he wrote the story, he was pretty sure the reader wouldn’t know either.

- E.L. Doctorow’s opinion: “Writing . . . is like driving a car at night. You only see as far as your headlights go, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

- Jerry Jenkins, coauthor of the Left Behind series, says he never knows what’s coming next. He once replied, when a reader asked him why he’d killed off one of her favorite characters: “I didn’t kill him off; I found him dead.”

Straddling the Fence

There are, of course, ways to compromise. Robert B. Parker suggests what I referred to earlier, a sort of “pseudo-outline”: block out a story in your mind, not on paper, and when you have it set, start to finish, sit down and pound it out. Another approach would be to jot down no more than a few sentences about several scenes in your story, and leave the ending up in the air. That way maybe you wouldn’t feel the confinement of an outline, but you’d at least have a direction. The thinking here is that anything would be better than nothing.

So that’s it. What do you think? Are you an outliner or a freewheeler? An OP or a No-OP?

Whichever side you sit on, however you reach your destination, I wish you well.

- John requested that I add a footnote explaining this graph, which I chose (and he approved) to illustrate his column. The image is a graphic outline of the nodal structure of Criminal Brief, created by means of an online Java applet. Click on the image to visit the website where it was generated. —JLW [↩]

I think I’ll go with E.L. Doctorow on this one–I never outline, and I don’t think that it has hurt my writing any over the past 25 years. The closest I come to an outline is the stuff already worked out in my head by the time I sit down at the keyboard and start writing … and since that means I already have it, I don’t need to put it down on paper.

I know what you mean, Joseph. The “stuff already worked out in your head” that you mentioned is usually my way of outlining as well. That seems especially ideal for short fiction.

I would agree that whatever works for you — and if it’s worked for 25 years, it certainly works — is the “right” way to do it.

Bob Crais writes outlines so thorough that they are several thousand words long before he starts in on the prose. In contrast, Jan Burke puts her characters into a situation and then follows them wherever they decide to go—but she also closely conforms to the hallowed “three act structure”, which I have always regarded as an outline template.

Scott Phillips uses a method he calls “drafting”, i.e., there is no outline, but his first draft is a bare bones sequential narrative without any refinements of language whatsoever.

I don’t outline in any strict sense, but I do establish a sequence of plot points. When actually composing a story, I start at one plot point and keep going until I reach the next one, without really ever knowing how long it will take. Sometimes I change the sequence of plot points for dramatic effect or economy. I might also drop or add new points as they obviate or suggest themselves.

I’ve found (says mr.-semi-pro-writer)that an outline or synopsis of a scene serves as a goad to get me off my behind and finish writing the thing. Craig Rice wasn’t kidding when she decribed how to write a mystery by putting paper in the typewriter, typing the title and your name and then you’re on your own! Great post, John! You are one of the good teachers!

This is the truth: A writer friend who’d published several suspense thrillers years ago told me she recently had so much difficulty trying to publish a current novel that she decided to condense it to short-story length (about 10K words) and then sold it that way instead.

When I asked her how in the world she was able to cut that much out of a manuscript and still make it work as a story, she said, “It was easy — I had a 75,000-word outline to work from.”

Great column, and perhaps the most intelligent discussion of outlining I’ve encountered.

I’m with Loren Estleman in this. While a writer doesn’t need to know the entire route before starting a story, knowing the destination helps assure that he/she will get there. Fortunately, the mystery genre has a general purpose destination built in: the mystery/crime will be solved and justice will prevail. More or less, anyway.

I’ve read plenty of fiction (outside the mystery genre) from which it was obvious the author had no idea where he/she was going.