Wednesday, July 9: Tune It or Die!

THE STYLE IS THE SUBSTANCE

by Rob Lopresti

I shouldn’t be writing this. For once I am working on a deadline: writing a story for an anthology and I have just under a month to turn something in. For a guy who usually takes years to fine tune a story, this is crazyland. But I have a good tale to tell and I want to get into the anthology, so I’m taking my best shot.

I’m writing this particular story in a very affected style, which is unusual for me. I normally try to make the style transparent—you shouldn’t notice the writer. But this story depends on the style. Done in standard grammar and nice neat paragraphs, the tale itself would disappear. I don’t know whether it will work, and whether the editor will buy it. But this is what the story must be.

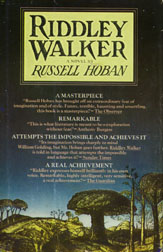

All this has me thinking about other tales that depend on their style. Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker is one of my favorite novels. It’s post-apocalyptic science fiction, taking place hundreds of years after a nuclear war and the thing is, it is written in the English of that horrible, primitive future time. Here is the opening sentence:

On my naming day when I come 12 I gone front spear and kilt a wild boar he parbly ben the last wyld pig on the Bundel Downs any how there hadnt ben none for a long time befor him nor I aint looking to see none agen.

Believe it or not, that gets slightly easier to read after a few pages. Most of the scholarly articles I have read about the book concentrate on the language, not surprisingly, and one critic did something very clever. He tried to translate the book into standard English. By the end of the first page he realized he had lost so much of the book’s meaning there was no point in going on. Hoban’s story needs this language.

Let me give two examples. A major theme of the novel is fission: “the 1 becomes 2.” This includes human beings dividing from nature, and mind separating from body. It is significant that the book begins on Riddley’s birthday when he turns 12 and if you changed 12 to twelve that connection would be lost (or at least obscured). Of course, another example of fission is splitting of the atom, which in Hoban’s world is spelled Addom – as in Adam, of course. So in this book the fall of man and nuclear war are the same event. The small vocabulary of Riddley’s people allows for double and triple meanings that standard English doesn’t experience.

That Philadelphia story

The Sixth Sense is another example. If you can remember back to the first time you saw that movie, you may recall some confusing parts where the continuity seems to be messed up. Bad editing, you mutter as it flows by. Only when the full story is revealed do you realize that the style was part of the story. The reason certain parts are left out is that in this case the missing parts didn’t happen.

The Sixth Sense is another example. If you can remember back to the first time you saw that movie, you may recall some confusing parts where the continuity seems to be messed up. Bad editing, you mutter as it flows by. Only when the full story is revealed do you realize that the style was part of the story. The reason certain parts are left out is that in this case the missing parts didn’t happen.

A master steps in

One more example from mystery short fiction (which, by an amazing coincidence, is the subject of this blog). Stanley Ellin was one of the best writers of short mysteries, period (and please don’t confuse him with Stanley Elkin or Aaron Elkins, both of which I have seen done). His story “The Payoff” is a taut little tale of murder-for-hire—until you get to the end and find out that it is something quite different.

One more example from mystery short fiction (which, by an amazing coincidence, is the subject of this blog). Stanley Ellin was one of the best writers of short mysteries, period (and please don’t confuse him with Stanley Elkin or Aaron Elkins, both of which I have seen done). His story “The Payoff” is a taut little tale of murder-for-hire—until you get to the end and find out that it is something quite different.

But this is not a twist ending for the sake of the twist. If you go back and reread the paragraph that explains what was going on—the “payoff” in more senses than one—you will realize that the fact that most readers wouldn’t understand what was happening was the very point Ellin was making. If he had told the story in a straightforward manner, it wouldn’t have had the same meaning.

And now I have to get back to work. I have approximately 5,000 words to bang into shape by the end of July. But first …

Another thread from the web

Last week I broke a rule of netiquette. When you see a cool website and mention it on your blog, you are supposed to give credit to the webpage where you discovered it. When I noted Wordle I should have said that I found it via the Straight Dope. This website’s motto is “Fighting Ignorance Since 1973. (It’s taking longer than we thought.)”

Cecil Adams, “the world’s smartest human,” will attempt to answer any question with a mix of accuracy and sarcasm. He really does give terrific information on everything from basic physics (“The second law of thermodynamics, simply put, is as follows: left to themselves, things tend to go to hell in a handbasket”) to the musical score of Flash Gordon serials (“American movie makers have always held a deep reverence for composers whose works lie in the public domain.”)

Cecil Adams, “the world’s smartest human,” will attempt to answer any question with a mix of accuracy and sarcasm. He really does give terrific information on everything from basic physics (“The second law of thermodynamics, simply put, is as follows: left to themselves, things tend to go to hell in a handbasket”) to the musical score of Flash Gordon serials (“American movie makers have always held a deep reverence for composers whose works lie in the public domain.”)

And you can be sure that Mr. Adams will always address his correspondents with the warmth and deep respect that is his hallmark. “If ignorance were corn flakes, John, you’d be General Mills.”

Rob,

Enjoyed your column today.

I once assigned a class to rewrite the first three pages of Huckleberry Finn in standard English. Mark Twain would have enjoyed the results! (Yes, I taught this book even though it has the n-word. We substituted “Friend,” creating Friend Jim.)

Wonder why in the quoted passage from Riddley Walker wild is spelled “wyld” one place and correctly the other?

I would think both would have been spelled creatively.

Good luck on the anthology story!

Rob, best with the deadline! Thinking of SF, Zenna Henderson’s style is incredibly captivating (reminds me of Bradbury) and don’t miss the degeneration of the narrator’s prose in Kings “The End of the Whole Mess.” As for confusing Ellin, I once heard a radio show host introduce a jazz bit by pianist Erroll Garner as being “by the author of the Perry Mason books…”

I love the perry Mason reference. Thanks.

The “wild” is my bad. Hoban used “wyld” both times. My internal spellchecker corrected one of them.

Enjoyed your post, and good luck with your story. Please let your readers know when it will be available to read.

Just in case anyone rereads these old things, I thought I would mention I heard yesterday that the story sold. I will say more next year when the anthology appears.

Cheers.