Monday, July 14: The Scribbler

STYLIN’

by James Lincoln Warren

I frequently have the opportunity, or perhaps I should say obligation, of wearing evening dress. Recently I entered into a polite dispute with regard to how one should wear a black bow tie with a wing-collared shirt. Should the tie be worn outside the wings, or inside? I took one position and my friend Ken Lombino took the opposite.

“Would you accept what they say in GQ?” he asked.

“Not if they take the wrong position. That’s just another reason not to read GQ.” (The Gentle Reader may perceive that I think most of GQ’s advice isn’t so much fashionable, as it is faddish.)

“What about Brooks Brothers?”

“Since when does the merchant dictate to the gentleman how to dress? It’s supposed to be the other way around.”

But Ken has a good point—his opinion is the more common.

According to the Black Tie Guide, “When worn with wing collars, bow ties are traditionally placed in front of the wings because the original collars were starched so stiffly that it was impossible to place their tabs over the bow. Etiquette aside, this positioning is also the more practical choice as the collar’s wings help to keep the bow in place by pressing it forward.”

This supports Ken’s position.

To which I say, “Bilge-water.”

First of all, one doesn’t “place the tabs over the bow.” One tucks the tie under the wings, where it is securely held. Secondly, why would one want the shirt to press the bow forward? One doesn’t wish to look like a clown.

The Black Tie Guide also claims that “in Britain … the turndown collar is traditionally the only option for black tie as authorities such as Debrett’s regard the wing collar as the exclusive domain of white tie.” Well, Debrett’s might say so, but the reality in the U.K. is distinctly different.

Lots of fashionable men in Britain wear black tie with wing collars, and they have done so since the 1920s.

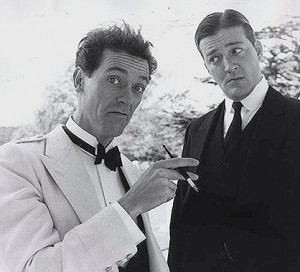

Bertie Wooster (interpreted here by Hugh Laurie) was always attempting to stretch the boundaries of elegant dress, much to Jeeves’ dismay (as silently but eloquently expressed by Stephen Fry). But what is raising Jeeves’ ire isn’t the fact that Bertie is wearing a wing collar, although part of it may be due to the tie being in front of the wings: no, it is the fact that Bertie is wearing a particularly noxious white dinner jacket acquired during a solo sojourn in Monte Carlo. (Jeeves and Bertie, one recalls, were constantly at sartorial war. There was the soft v. stiff shirt front controversy, and also the episode of the purple socks.) If you can’t trust Jeeves, then you can’t trust anyone.

Bertie Wooster (interpreted here by Hugh Laurie) was always attempting to stretch the boundaries of elegant dress, much to Jeeves’ dismay (as silently but eloquently expressed by Stephen Fry). But what is raising Jeeves’ ire isn’t the fact that Bertie is wearing a wing collar, although part of it may be due to the tie being in front of the wings: no, it is the fact that Bertie is wearing a particularly noxious white dinner jacket acquired during a solo sojourn in Monte Carlo. (Jeeves and Bertie, one recalls, were constantly at sartorial war. There was the soft v. stiff shirt front controversy, and also the episode of the purple socks.) If you can’t trust Jeeves, then you can’t trust anyone.

Now regard Lord Peter Wimsey, the very epitome of the Man About Town. This illustration was drawn in 1926 by John Collier. The aristocratic detective is depicted wearing a wing collar and a black tie. The observant Gentle Reader will surely notice that Wimsey, like Wooster, wears his tie outside of the wings. But I am not therefore capitulating. Au contraire—I am preparing my return salvo. I only showed these two depictions to explode the scurrilous canard concerning British gentlemen not wearing wing collars with black ties.

Now regard Lord Peter Wimsey, the very epitome of the Man About Town. This illustration was drawn in 1926 by John Collier. The aristocratic detective is depicted wearing a wing collar and a black tie. The observant Gentle Reader will surely notice that Wimsey, like Wooster, wears his tie outside of the wings. But I am not therefore capitulating. Au contraire—I am preparing my return salvo. I only showed these two depictions to explode the scurrilous canard concerning British gentlemen not wearing wing collars with black ties.

In 1936, Alfred Hitchcock directed an espionage thriller based on a 1928 collection of short stories by Somerset Maugham called Ashenden; or the British Agent, a work sometimes credited with originating “the modern spy story”. (The stories were partly based on Maugham’s experiences as an intelligence operative for the British government during World War I.) The movie was called “Secret Agent”. The hero, Richard Ashenden, was portrayed by John Gielgud.

Here he is with the beautiful Madeleine Carroll in a Swiss casino—and you will note that he wears his tie under the wings of his collar. The villain, a German agent posing as an American adventurer, was played by Robert Young. He wore his tie over the wings of his collar—in stark contrast to Good Guy Gielgud, who was also his rival for the affections of La Carroll. Perhaps it merely demonstrated an American preference for how to wear a black tie, but it identified Young as a bad ’un in my book.

Here he is with the beautiful Madeleine Carroll in a Swiss casino—and you will note that he wears his tie under the wings of his collar. The villain, a German agent posing as an American adventurer, was played by Robert Young. He wore his tie over the wings of his collar—in stark contrast to Good Guy Gielgud, who was also his rival for the affections of La Carroll. Perhaps it merely demonstrated an American preference for how to wear a black tie, but it identified Young as a bad ’un in my book.

And finally, allow me to introduce Mr. Jack Maddox (played by Aden Gillett), husband of 1920s fashion designer Beatrice Eliott in the (exhaustively researched, as with all BBC period pieces) TV series, “The House of Eliott”. Now I ask you—would any man married to a fashion designer commit such a faux pas as to wear his tie incorrectly? Of course not. Any man who’s been married for more than a month knows that such a course of action is tantamount to suicide—it is not only their daughters to whom women direct the dreaded question, “You’re not wearing that, are you?”

And finally, allow me to introduce Mr. Jack Maddox (played by Aden Gillett), husband of 1920s fashion designer Beatrice Eliott in the (exhaustively researched, as with all BBC period pieces) TV series, “The House of Eliott”. Now I ask you—would any man married to a fashion designer commit such a faux pas as to wear his tie incorrectly? Of course not. Any man who’s been married for more than a month knows that such a course of action is tantamount to suicide—it is not only their daughters to whom women direct the dreaded question, “You’re not wearing that, are you?”

By now the Gentle Reader has rightfully come to the conclusion that Your Correspondent is quite mad, and is asking, “What possible relevance does any of this have to mystery short stories (W. Somerset Maugham, P. G. Wodehouse, and Dorothy L. Sayers notwithstanding), and why has the perilously unhinged Warren taken such a long and tortuous, not to mention numbingly trivial, path to get there?”

Because I’m actually writing about style, and how it resides in the details. I’m not addressing the broad differences in style between a man dressed for the symphony and a guy tricked out for a hip-hop club. For their respective environs, each may be perfectly attired. But within the conventions of those environs, it is the details of their clothing that spell the difference between fashion success and fashion failure. It is the same with written language.

I was once excoriated on a listserv for putting periods and commas outside of quotation marks, a perfectly good British practice that is not often done in the U.S., but a couple examples of which you may detect in my discussion of Maugham above. The critic opined that I was being ostentatious, using a British convention when there was a perfectly good American one. Well, I can be monstrously ostentatious, it is true, but in this I am motivated by logic rather than snobbery. (And for what it’s worth, I generally prefer American conventions.)

Quotation marks are a form of what formal grammarians call delimiters. A delimiter marks the end of an “expression”, or a sequence of letters or characters grouped together for a specific purpose. 1 Quotations qualify as defined expressions: everything between them is supposed to accurately reproduce that which is being quoted. So if the punctuation doesn’t come from the source of the quotation, it doesn’t belong inside the quotation marks, and Yankee convention be damned.

In itself, this particular example may not be important, but in the aggregate, conventions of style carry considerable weight. Consistency is crucial—it’s why most publications adhere to a “house style”.

Really fine writers have a firm grasp on style and use it to convey more than merely what’s in the words. They’re as careful with the details of each sentence as if they were engraving currency. And the details matter a lot—being just slightly off balance will tip a sentence, a paragraph, even a whole story, off the rails entirely. It can be the difference between the sublime and the ridiculous.

One should read Maugham, or Wodehouse or Sayers or any great author, at least twice: first for the story, and then for the sheer delight of reading fine prose. There is an aesthetic to craft for its own sake, the beauty of a thing well executed that goes beyond its function. This is as true of fiction as it is of, say, Shaker furniture.

But getting back to the black tie and wing collar controversy: in actuality, there is no absolute authority, and anyone who thinks there is must be suffering from delusional ideation. It’s really simply a matter of personal preference, like whether one wears a pique (peak?), notched, or shawl lapel on one’s tux. Kind of like the words you use—and choose.

- Other examples: spaces are used to delimit words, commas or parentheses commonly delimit interposed phrases, a period is the delimiter of a sentence, and a carriage return delimits a paragraph. [↩]

Kudos for recommending Wodehouse and the Jeeves and Wooster books. Wodehouse is a delight to read if just because one can sense how much he enjoyed writing.

JLW,

You are the only person in the world who could start of with bow ties, segue to quotation marks and keep me reading to the end of the column.

I think of style as the shape of my story. How it looks on the page, and how it sounds when read aloud. I have spent hours restructuring a sentence until it looks sounds and feels the way it should in that particular story.

Terrie

You are the only person in the world who could … keep me reading to the end of the column.

Yes, as much as one would like to deny it, there is something ghoulishly riveting in the conduct of an obsessional lunatic.

Seriously, Terrie, thanks for such a lovely compliment.

James,

I love all this stuffy stuff, and that you write about it.

Wing collars are too short to hold the ends of the bow tie. I love your column, but is it not a matter of tailoring? Or editing?

Never trust a man who wears a bow tie!

My earlier post was rash. I should qualify: Never trust a man who wear a bow tie unless he’s in formal dress.

Now, as far as over or under, the only wings I care about are Madeleine Carroll’s. I’d like to. . . I digress (lasciviously).

Vis quotation marks, I follow the American convention even though I find it illogical. I’m just a conventional guy. (Which reminds me, I’ve signed up for Bouchercon!)

Since James mentioned Sir John Gielgud’s portrayal of Ashendon, I should point out an important mystery connection: Sir John’s big brother, Val Gielgud, was a pretty prolific mystery writer. He worked extensively for BBC Radio and later television, and included his experiences in the novel Death at Broadcasting House.

Steve, I wear bow ties all the time, and not just when I’m going formal. I would amend your post to say, never trust a man who does not tie his own bow tie.

Melodie, the tie actually goes under the wings and stays there. What does make a difference is the height of the collar. Either way, I absolutely do not understand why anyone would want to hide the wings behind the tie—it seems to me it defeats the entire purpose of a wing collar to begin with..

Having tried to send the following blog to your address listed on Google and being told it doesn’t exist, I am posting it here instead, this confession to being a member of PHARTS:

In an admirable display of modesty I have until now kept quiet about qualifying for membership in the Professional Hack Authors RecogniTion Society. Its acronym is PHARTS. Because of my maturity I have achieved the highest of all honors, the designation of Old Phart.

James Lincoln Warren, our Sublime Imperial President-for-Life, is the man responsible for seeing that writers such as myself have at long last received the recogniTion we deserve. JLW is a noted writer of mystery short stories. You can find his work in places like Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine and at https://www.criminalbrief.com/.

At the latter site you will find essays by seven fine mystery writers including JLW, Leigh Lundin and John M. Floyd. Once a week each writes an interesting piece on whatever strikes his fancy at the moment. At times there may even be mention of crime and mystery. Yesterday, for example, JLW tells readers everything they need to know about dressing for black tie affairs. This, I must admit, is not a problem frequently encountered in my life, yet it was most interesting. Recently Lundin wrote about killer hobbies, something many of us didn’t realize exist aside from bungee jumping and skydiving, pastimes that are activities and don’t actually qualify as hobbies. Having read the story, I am now aware that killer hobbies are out there waiting to…well, kill you. So if you are not a reader of criminalbrief, I highly recommend it. Like PHARTS, it was founded by James Lincoln Warren himself. What more can be said?

Gentle Readers may recall my going on and on some time ago about my cover story in the October 2007 issue of Hitchcock. The Observant Gentle Reader will perceive that Dick Stodghill‘s name is also on the cover of that magazine. That’s one of the reasons I’m so proud of it.