Sunday, 20 July: The A.D.D. Detective

The ROMANCE of MURDER

by Leigh Lundin

10 June, 1860, 1AM

|

| The Times 11 Jul 1860 |

The family dog barked and yipped in the night, but no one paid attention. The residents slept on.

Despite the peace of the Wiltshire countryside night, all was not well. In the nursery, one little bed at Road Hill House fell empty, its mattress still warm. The nursemaid nearby snored softly, unaware evil was afoot.

Outside, the door of the servant’s privy creaked. The dog barked again, but no one heard. With a piteous howl, the Newfoundland sensed what no one else knew– a little life snuffed out.

The household slept on.

The nursemaid awoke at dawn. Elizabeth noticed the tiny bed was empty. Mrs. Kent must have taken him, she reasoned. Mary, once a governess herself before becoming the second wife of Mr. Kent, often did that.

Not until 7AM did Elizabeth and Mary realize 3-year-old Saville was missing. The Georgian manse housed twelve, including three of their servants. Frantically, the family searched the house, to no avail.

Outside, neighbors took up the hunt. As incentive, Mr. Kent offered £10 reward, more than $1000 in today’s currency. As men trampled the grounds, the dog barked maddeningly.

His eyes were closed, almost peaceful, despite having his throat cut before being dumped into a chasm of shit.

The crime was so horrific, it captured the imagination of Victorian England. Historically, the crime and its solution helped create a literary landmark, the modern detective novel.

Police had no shortage of suspects. The list included:

- Samuel Kent, father

- While married to his first wife, the first Mary who had gone quite mad, in the English sense, while Kent buried possibly five of the ten children she bore. Kent was rumored to have had an affair with his governess, who became the second Mrs. Kent. Some said he was mean and ill-tempered pointing to a succession of more than 100 servants who’d traipsed through his household employ.

- Mary Kent, mother

- Caught in a Jane Eyre triangle, she moved with Kent to escape rumors, three houses in four years. She might have been jealous of the nursemaid, but would an eight month pregnant mother harm her own toddler?

- Elizabeth Gough, nurse maid

- Would she have harmed one of her charges? Was she having an affair with the master of the house or perhaps the local cobbler? Did she silence the child to prevent him tattling to his mother?

- William Nutt, shoemaker

- He was rumored to be the lover of Gough, but could he have killed the child in a jealous rage? Could he have murdered to protect his secret affair?

- The gardners …

- The stablehands …

- The butler …

The local constabulary rapidly developed a theory and arrested the governess, Elizabeth Gough. Superintendent John Foley believed it was impossible for the boy to be abducted without his nurse’s knowledge.

Police theorized that the boy awoke and saw the nursemaid and her lover (possibly either Nutt or Mr. Kent himself) going at it. To silence the boy, they smothered him and cut his throat to throw police off the scent by shrouding the cause of death.

Which man was her lover? And did police lock up the right suspect? London’s papers wanted to know, calling for a higher investigation. They prevailed upon the Home Secretary to bring in the successors to the Bow Street Runners, not yet two decades old, Scotland Yard’s Metropolitan Police.

Which man was her lover? And did police lock up the right suspect? London’s papers wanted to know, calling for a higher investigation. They prevailed upon the Home Secretary to bring in the successors to the Bow Street Runners, not yet two decades old, Scotland Yard’s Metropolitan Police.

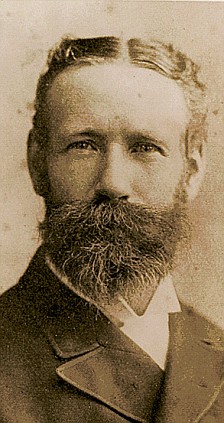

Britain had only eight detectives in the land and rarely did they leave London town. They chose their ‘prince’, perhaps a rumpled Columbo of a man to modern readers, Detective Inspector Jonathan Whicher, and a colleague, Adolphus Williamson.

Jack Whicher had pale skin offset by sharp blue eyes. His mousy brown hair and beard helped obscure his pox scars. Writers described him as short, stout, scuffed, shabby, grizzled and grim. Charles Dickens wrote that the rumpled detective possessed "a reserved and thoughtful air, as if he were engaged in deep arithmetical calculations."

Whicher had his work cut out for him. He interviewed and pieced together evidence and even a kind of psychological profile. In the end he pointed the finger at …

Jack Whicher arrested sixteen year old Constance, daughter of the first Mary Kent. He believed she had the strength, the will, and the motive to kill her little brother.

Convinced Whicher had it wrong, the indignant Wilts County magistrate ordered the girl released.

Whicher appeared defeated and disheartened when he retired four years later from the Metropolitan Police. He is said to have told a friend, "We will only know the truth when Constance Kent confesses." Meanwhile, Constance had taken up residence in St. Mary’s Home for Religious Ladies.

Nearly five years after the murder, 21-year-old Constance, holding the arm of a priest, entered London’s Bow Street Magistrates’ Court where she asked to speak to someone of authority. There she confessed to killing her half-brother, little Saville Kent.

She eventually revealed she despised her new stepmother, resentful that her governess had become the new materfamilias, replacing her own mother. In her hatred, she killed her stepmother’s child.

Britain still had the death penalty in force. The magistrates sentenced Constance to hang but– as we’ve discussed in these columns– Queen Victoria commuted the young woman’s sentence to twenty years.

Jack Whicher died in 1881. Four years later, two and a half decades after she’d committed murder, Constance Kent emerged from prison and disappeared. She was 41 years old.

The events of a century and a half ago remind us of today’s headlines. London papers reflect upon recent British murders.

I happen to think of JonBenét Ramsey, the beauty pageant princess killed at Christmas 1996.

I recall an hour-long television interview with a Boulder detective in which she pontificated she knew the killer was the father, John Ramsey. She claimed she was certain within the first few minutes, her evidence being the odd dollar amount in the ransom letter, its handwriting and stationery, and how long it took John Ramsey to find his daughter. She discounted anyone climbing in through the basement window.

I remember thinking "this is wrong". Her mounting psychological ‘evidence’ against John Ramsey was predicated on disbelieving the physical evidence! It now seems likely an investigator hired by the Ramsey’s correctly identified the killer and cause of the crime, but it grows ever more doubtful that it will ever see a day in court.

What has happened here? Thanks to Jack Whicher and readers of London’s newspapers, many of us have become armchair detectives. The Victorians made a romance of crime, the ‘cosy’. If the public hadn’t smelled something wrong and made an outcry, nursemaid Elizabeth Gough and perhaps an innocent man might have swung at the end of a gallows’ noose. It’s happened before and as long as we have capital punishment, it will happen again.

Police detectives are good and sometimes they’re bloody damn great, but amateurs have had their say as well, which is attested to every day on TruTV (formerly CourtTV) and numerous stories. Many credit Jack Whicher and the Kent case with paving the way for the modern detective story, including Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and eventually Agatha Christie.

When Sir Robert Peel founded Scotland Yard‘s Metropolitan Police, he did it with the help of men like Whicher and especially Francois-Eugene Vidocq, once a criminal who founded the Sûreté Nationale and became one of the first modern private investigators. Vidocq was the prototype for Émile Gaboriau‘s Monsieur Lecoq and Victor Hugo‘s inspiration for both the sympathetic criminal Jean Valjean and his nemesis, police inspector Javert, in his novel Les Misérables.

American detectives draw inspiration from the same events. Naturally, we trace another major source to Edgar Allan Poe whose Auguste Dupin appeared nearly twenty years earlier. (It should be noted that there were earlier stories of detection, Voltaire, for example, and Chinese tales before that. Even the Bible contains examples that could loosely be described as detection.)

The British have been doing a bit of well-deserved backslapping in The Times. I admire (and agree with) their description of detection as reason conquering evil. They might extend a bit far (in my non-British opinion) in laying claim to all things detective, but at bottom they’re right that Dickens and Collins and of course Doyle laid the greater foundation for detective fiction.

They’re also on the mark that we should applaud amateurs who fight crime and injustice. In particular, they celebrate writer Kate Summerscale. Tuesday at the Royal Festival Hall, BBC Four awarded Kate the Samuel Johnson Prize for The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher, which carries a £30,000 honorarium. Yes, most of us starving writers are asking ourselves, "Thirty thou’ quid? Wot’s that like?"

Constance Kent, by the way, sailed to Australia the year after her release under the assumed name of Emily Kaye. There she worked as a nurse, apparently well into World War II.

Constant Kent, a child who murdered a child and launched the romantic era of crime, died at age 100.

A marvelous lesson in how the truth can inform not only individual works, but an entire genre. Thanks, Leigh!

Wow! I didn’t know this story!

What an interesting story! Thanks for sharing this one…it gave me goosebumps.

better late than never—enjoyed this—very interesting indeed and “skeery eery”.

What an awful version of this story.. so Americanised…. This is a facinating case and all other accounts I have read of this are well written and documented, this piece however is splattered with ‘chasm of shit’ and ‘a Columbo of a man’ – what lazy horrible writing.

Thank you for taking the time to write, Clare. The ad hominem spam filter trapped your message and it took a while to reach me.

Whether the writing is horrible can be open to question but lazy– never. Not counting earlier reading, that little article took more than half a week to research, write, edit, re-edit, format, pull graphics, link, edit, post, and… re-edit.

It’s true I’m usually irreverent and I’m often flippant, but I care– I care a lot. The horror faced by two children a century and a half ago infuriates me as any current crime against children– and I include child perpetrators whom our ‘modern’ society today refuses to recognize as victims (which leads to another story I’m working on).

Although I lived and worked in the UK, we know our audience is largely North American (predominantly US and Canadian) who might be unfamiliar with the British tragedy, hence the Columbo reference. We’re mainly storytellers and, although all of us are university trained (one or two of us never quite left that environment) and we occasionally slip up and release an erudite scholarly article (mostly thanks to James), we tend to write conversationally as if we’re sitting across from you. That’s why I appreciate your taking part in our dialogue.

You’ll note in my writing that I rarely utter any curse, swear word, or obscenity, but, as you point out, I departed from that practice and referred to the “chasm of shit” under the outhouse. The vast majority of the English-speaking vitreous porcelain-sitting world has never visited an outhouse. It is not a dainty dell of doo-doo nor an evanescent excrement environs or even muck in a mare’s stall, but a nasty, stinking hole with stalagmites of feces that, thanks to a British invention, Westerners will never again encounter. I know whereof I speak.

Into this putrid mess a human child was hurled. I want you to be offended. I want you to be outraged– not at me, but what happened to a little boy, and yes, his sister.

The story hints at another potential obscenity (as your comment may have alluded), the penchant of the press for turning tragedy into entertainment today as it did 150 years ago. According to psychologists, it’s a way some people cope. The Kent case became pivotal in police work and it turned out to be pivotal in English (and French) literature.

Stepping away from the tragedy itself, North Americans recognize our indebtedness to the British for crime literature. Individuals within our group are close to Ellery Queen and Alfred Hitchcock, both publishers of British fiction which we cannot devour enough of. Don’t misunderstand us– when we speak of British crime writers, whether fictional or factual, we do so with respect.

I hope you write again, Clare, and I look forward to hearing from you.