Monday, March 29: The Scribbler

HIGH INFIDELITY

by James Lincoln Warren

If the Gentle Reader is passing anywhere near a magazine rack anytime soon, stop and pick up The Strand Magazine‘s Feb-May 2010 issue, and while you’re at it, see if you might also put the June 2010 issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in your shopping bag (after paying for it, of course). The former features John M. Floyd’s most recent offering, “Reunions”, and in the latter’s Black Mask department, please find “Jungle Music”, authored by your Faithful Correspondent.

They are very different crime stories by two very different writers, but they contain a common thread, one very common in crime fiction. In both stories an act of sexual infidelity is central to the plot. This is, of course, a classic theme.

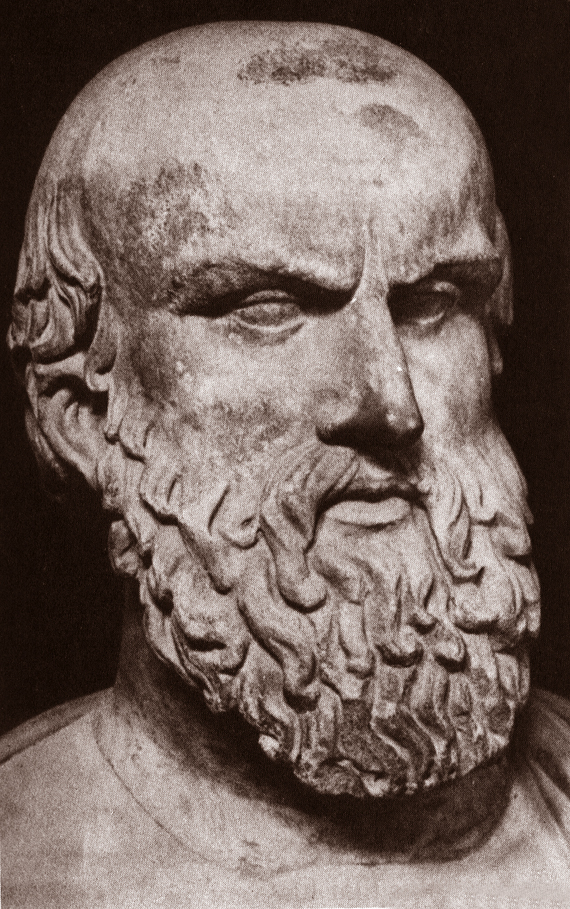

Sherman, set the Wayback Machine to 458 B.C., so we can meet Aeschylus, author of The Oresteia. The ancient Greek myths are full of infidelities and their consequences, culminating in the Trojan War. We all know how well that turned out. As Mr. Peabody said, or should have said if he didn’t, “Beware of gifts bearing Greeks.”

Sherman, set the Wayback Machine to 458 B.C., so we can meet Aeschylus, author of The Oresteia. The ancient Greek myths are full of infidelities and their consequences, culminating in the Trojan War. We all know how well that turned out. As Mr. Peabody said, or should have said if he didn’t, “Beware of gifts bearing Greeks.”

But before we arrive, some thoughts.

The great thing about infidelity, as far as character development and motivation is concerned, is that it comes standard with the full deluxe accessory package already installed. It turns on a dime and can go off in any direction by pivoting on two of the worst flaws in human behavior: lust and deception.

Lust, of course, is nothing other than a specific manifestation of greed. (Three of the Seven Deadly Sins are variations of greed: avarice, lechery, and gluttony. In case the Gentle Reader is struggling with remembering the other four, they are wrath, sloth, pride, and envy. Deception didn’t make the list because it isn’t always motivated by selfish reasons.) In a crime story, Greed is always good, although not in a Gordon Gekko kind of way.

Deception is central to crime fiction, too—it’s what puts the mystery in mystery fiction.

Hey, we are in classical Athens just in time for the Dionysia, the annual dramatic Festival. The show we’re about to see is called “Agamemnon”. Agamemnon, King of Kings, has just returned home from a decade at the office in Troy, and is about to be murdered at the hands of his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus. Aegisthus is a dupe, egged on by Clytemnestra for her own ends. More murder ensues.

Back to modern times, Sherman.

This formula is famously repeated in a ton of noir fiction, most notably in James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice, and again in Lawrence Kasdan’s “Body Heat”. What makes it work is that the lust and deception involved manifest themselves at different levels. Walter Neff in Indemnity and Frank Chambers in Postman are motivated to murder by their lust for a beautiful woman, and enter into the deceit required by the murders because that lust burns so hot they’ve lost control of their own lives. The two women, though, Phyllis Dietrichson in Indemnity and Cora Smith in Postman, are deceitful even in their lust—they are actually using their sexuality in the most cold-blooded manner possible in order to manipulate the men. I love that contrast.

These stories have been criticized by feminist critics on the grounds that they depict female sexuality as predatory in nature, a criticism also leveled at the idea of Original Sin, whereby Eve seduced Adam into eating the Forbidden Fruit, and therefore a culturally systemic means of repressing women. There may be some truth to that, because certainly in real life, men are just as likely, or even more likely, to sexually manipulate women than vice versa. All that aside, though, it’s the contrast between the two killers in each story that is the mainspring of each story’s tension, a device that is perfectly suited to the action because there is sexual tension to begin with that is intensified by the crimes.

Another great thing about infidelity is that the one thing you can be sure of is that it will inexorably lead to very bad unintended consequences—you can predict that something unpredictable is going to happen, and that it won’t be wearing a Happy Face. That makes it a particularly rich vein to mine for plots.

As with John and me. I mentioned that they are very different stories, and they are. John’s story features that characteristic touch of irony I look for from him, surgically injected into what at first glance appears to be a slice of life. Mine, on the other hand, begins with a sensational crime that leads my private eye protagonists on a journey to an unpalatable truth. His is about 4,000 words long and mine’s about 10,000, both of them exactly the correct length for the kinds of stories that they tell.

Neither of us is unfaithful to the reader, after all.

That could lead to very bad things.

JLW: So wonderful to begin Monday morning with Professor Peabody and his boy, Sherman. I compliment you on your choice of companions.

Jungle Music was one of my favorite short reads of the couple of years, well, worth the price of the magazine.

Greed. Lust. Sex. Crime. Writing.

No better way to start a week.

I meant…

“…reads of the LAST couple of years.”

LAST.

Geez, how come this comment section doesn’t have an editing button?

Why don’t I just learn to proofread my own stuff?

All this talk of naughty things has got my glasses all foggy.

Stop me before I comment again.

Interesting column as usual, JLW. And certainly everyone’s favorite Deadly Sin.

Thanks, by the way, for the plug.