Thursday, August 19: Femme Fatale

SHOW ME A STORY

by Deborah Elliott-Upton

If one picture is worth a thousand words, how many pictures would one short story be worth?

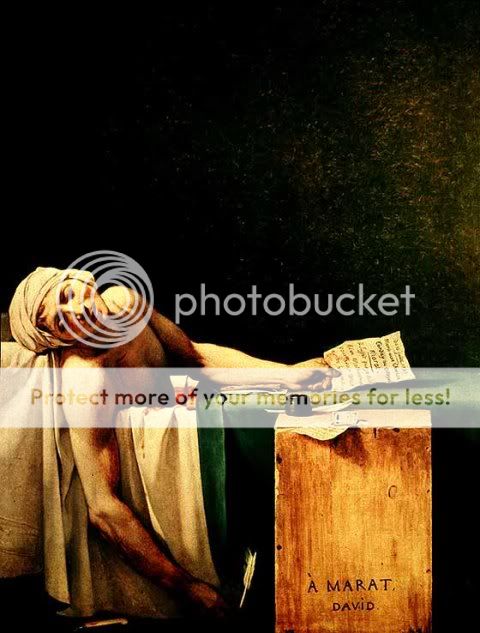

I was thumbing through an art book and stumbled upon a painting by Jacques-Louis David, La Mort de Marat (The Death of Marat), that had always fascinated me. When I was younger, I didn’t think of it so much as a crime scene, but in fact, that is exactly what David captured. The corpse, a letter in his hand from the assailant asking for an audience with him and the murder weapon, a knife on the floor, is displayed.

If I remember correctly, there was a witness and so no doubt as to who the murderer was, and therefore little to classify this sight as a mystery, but suppose we had written a short story concerning this crime scene? And for us, the short story lover, the game is afoot, my dear friends.

Consider our victim. Marat was a prominent doctor in 1770s London when he was appointed physician at the French court of Louis XVI’s brother, the Count d’Artois. Marat was known for his published scientific writings, but also as an author of inciting political pamphlets. Marat won many followers from the lower stations in France, but also made many enemies. See the conflict?

Our killer was a young woman who during the French Revolution was a Girondin supporter – enemy of Marat’s advocacies of an extensive social legislation programs. History tells us Charlotte Corday came to Marat’s Paris room and stabbed him while he soaked in his bath. The murder was certainly premeditated since she brought the weapon with her. She was rewarded by being sent to the guillotine and instead of making him go away, propelled Marat to become a martyr.

But what if there had been no witness? Or what if he himself were an accomplice? In studying the painting, would there be any clues not noticed by the police? It’s known Marat was ill with some sort of need for medicinal baths. It’s known that whatever condition he had was excruciating and the frequent and lengthy baths were the only method of relieving the pain. Could he have been in such torment that he took his own life in order to make the opposing side take the blame?

Was an innocent woman killed when she only wanted to plead with Marat to see the other side of the cause? Would a jury (had there been a trial) have convicted Corday, or could she have gotten off on grounds of reasonable doubt? Personally, I have no idea if the French courts at that time considered reasonable doubt, but I am sure someone reading this probably does, so, please leave a comment so we will all know.

Would much depend on a competent lawyer or an amateur sleuth or two? Or on courtroom prejudices? Of the young woman’s beauty or lack of it?

A painting of one man’s death by his close friend and skilled artist surely leads to a thousand words we could say about the work. I suggest one short story can just as surely lead to many pictures in our minds, turning like a carousel of memories long after the story has reached its end.

Intriguing post on many levels. My eyes just glossed over the painting until your words made me think it was worth “investigating” – and since almost every mystery story by definition involves investigating, you’ve also given an answer to the age old question – “Where do you get your ideas from?” – “Why, from investigating….”

Michael

Love it when you make me think!! :]]

For some reason that painting always make me think of this cover from an album by Steve Goodman, who wrote City of New Orleans. http://tinyurl.com/3a2walo

Wow!

And what if the witness was the real killer and just framed the woman since she was lowly peasant and no one would believe her anyways.

Great post Deborah!

Corday was not a peasant. She was a lesser aristocrat. In any case, she confessed at her trial and was unapologetic about the murder, which she felt was for the greater good.

True, JLW, but we are playing a What if? game. The stories are abundant when we tweak only one thing about the truth, are theynot?

Of course we are playing a game of what if, but we should play fair, especially if we’re writing an historical—making Corday a peasant requires more than one tweak. In the first place, in Revolutionary France, a peasant girl would have much more credibility at a trial before the Assembly than any aristocrat. Secondly, if Corday were framed, there should be a reason why she confessed in court. How about she knew who really performed the foul deed but was in love with him, and did the far, far better thing by confessing to the crime in order to save him from Madame la Guillotine?

JLW’s and Deborah’s discussion about Deborah’s column is exactly why I no longer answer the question, “What’s your story about?” until the story is completely put to bed. Speaking of ‘vision’ here.

Both JLW and Deborah presented fascinating facts/ideas/conclusions drawn from the painting, although it sounds like JLW stuck closer to reality. However, it’s the writer’s vision of the story that counts in the end. Two writers may each produce a great story from viewing that painting, but the stories will never be, and shouldn’t be (from a reader’s greedy point of view) the same.

Darn, that’s a good post!

Angela– I agree and don’t talk about my WIP any more until it’s done. And yes, any two writers given the same exact info about a crime scene could compose different outcomes…which explains why there are so many differing creative nonfiction pieces out there concerning the same subject. Art is art because it is subjective to the viewer. I believe a story based on a crime scene — whether completely true or dramatically altered — is also an artform.