Wednesday, September 22: Tune It Or Die!

THIS IS NOT A RIP-OFF

by Rob Lopresti

I recently read “Shell Game” by Neil Schofield in the November issue of Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine and I recommend it, but that’s not why I bring it up.

You see, as I read it I had a nagging sense of familiarity. I guessed— correctly, as it turned out—exactly where the story was headed. There was a reason for that; I had driven that road myself.

Schofield used a plot device that I had used in the second story of mine that was published in Hitchcock’s way back in the 1980s. Put it this way; if you read my story first and then his (or vice versa) you would immediately know what was going to happen.

Some of you may expect to hear I am contacting a lawyer, hoping to deprive Neil of the vast wealth he acquired by swiping my story. Well, no. For at least two excellent reasons.

Going legit

First of all, I don’t believe for a minute that Schofield read (or remembered) my story that appeared decades ago and decided to steal a plot gimmick. I’m sure he came up with it on his own.

Second, and this is more important, even if he had done exactly that, it would still be legitimate theft.

The first time I came across that phrase was in the book Telling Lies For Fun And Profit by Lawrence Block. (And if you are interested in writing fiction you should definitely read all three of Block’s books on the subject. Telling Lies is the best.)

Block explained that he got a phone call from writer Brian Garfield telling him how much he had liked a novelette Block had recently published in (yes, again) Hitchcock’s.

What he said next was faintly unsettling, however. “I liked it so much,” quoth he,”that I managed to figure out a way to steal it.”

“Steal it?” said I. “Steal it?”

“Oh, it’s a legitimate form of theft,” he assured me. “You’ll see when it comes out.”

I countered by quoting Oscar Levant. “Imitation,” I pointed out, “is the sincerest form of plagiarism.”

“Couldn’t agree with you more,” said Brian, and rang off.

Block prefers the term creative plagiarism to legitimate theft, and when he read the story he agreed that that was what Garfield had accomplished. “His story directly derived from mine, but he had so adapted the idea as to create a completely different story.”

“The acid test, it seems to me,” Block adds, “is whether the plagiarist contributes something significant of his own devising to what he has borrowed.”

Unpleasant surprise

This is not the first time I had an experience like this. Not too long ago I read Lee Child’s excellent novel Killing Floor and had a startling sense of déjà vu. The opening page strongly resembles my “The Hard Case,” which appeared in (did you guess?) Hitchcock’s. Both begin with a stranger in a diner (eating eggs!) and being arrested on suspicion of murder. Surely Childs hadn’t copied me?

I checked the publication date and got a shock. Childs wrote his book almost a decade before I wrote my story. If anyone had done the copying it was me, and I swear on a stack of royalty checks I had never read his book until long after my story was published.

So, just as in the Schofield case, two writers came up with the same idea. Fortunately, my story goes in completely different directions from Child’s novel. But it is a scary reminder that there are only so many ideas out there.

The interviewer has a final question

But, tell the truth, Mr. Lopresti. Don’t you resent Mr. Schofield’s story at all?

Well, yes. I suppose I do.

Ah ha! Because it uses the same plot device as your story?

No. Because it’s better than mine.

A few years ago I got a personalized rejection letter stating that the magazine couldn’t use my submission because they were looking for “something original”. Unfortunately the magazine folded, so I never got the chance to submit again. I guess my point is that it was original to me!

Cindy, that reminds of a famous review that went something like this: “This book is good and original. Unfortunately the parts that are good are not original and the parts that are…” You get the idea.

Glad you wrote about this, Rob. You’re right, this kind of “theft” happens all the time, intentionally and unintentionally. Unless it’s TOO much like the first story, the worst that would probably happen is that the second story would appear — as Cindy said — unoriginal. It’s true that (like story titles) there are only so many ideas, and plots, out there.

I worry about this, too. But then who would bother to write after Shakespeare? And he stole from the Greeks.

The “good and original” quote is usually attributed to Samuel Johnson, and it certainly sounds like Johnson, but its true origin is unknown.

As Ecclesiastes observed a few thousand years ago, there is nothing new under the sun. My first Treviscoe story used a hoary plot device borrowed from an old episode of Banacek, but the story worked because I dressed it up in 18th century drag.

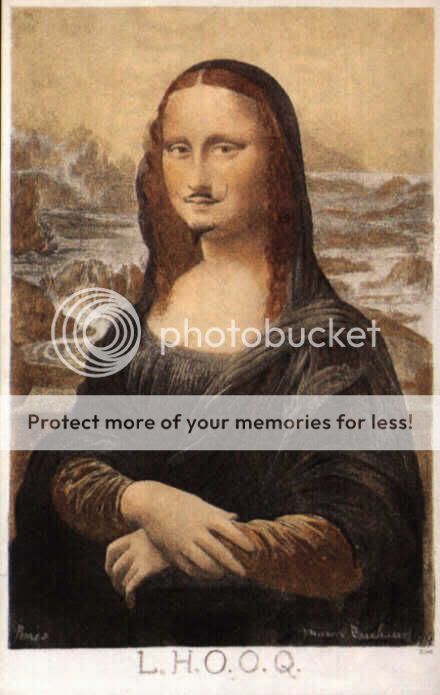

A cheeky definition from Wilson Mizner, playwright, 1876-1933:

“When you take stuff from one writer, it’s plagiarism; but when you take it from many writers, it’s research.”