Saturday, November 13: Mississippi Mud

PROLONGING THE AGONY

by John M. Floyd

Several weeks ago, during a TV appearance to promote my new collection of mystery short stories, I was asked a question I hadn’t heard before. The interviewer said, out of the blue, “Why do you think so many people like to read crime fiction?”

Say what?

After my heart starting beating again, I replied with something about the fact that readers like to see conflict in a story—the more the better—and with mystery/crime fiction, some level of conflict is always there. It’s already built in.

I believe that, and I thought it was an okay answer, but mulling it over as I was driving home from the studio, I thought of a better one (I often do, after the fact). The main reason readers like crime fiction is probably that we as human beings feel constantly threatened by the possibility of injustice and violence—and in crime stories justice is usually served in the end, and criminals get what’s coming to them. I think that gives readers a feeling of security and comfort and fairness that they certainly don’t get from the headlines they see in the newspapers every day.

Bad things happen to good people

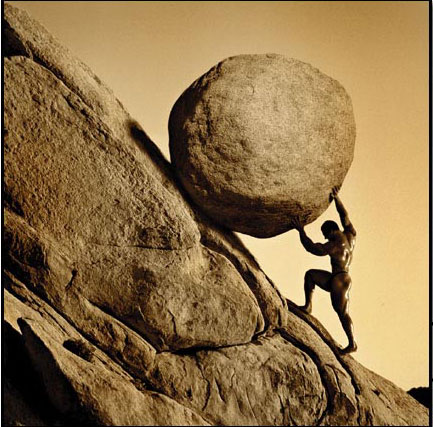

Enough speculation, though; here’s something I’m actually sure about: the more problems that I as a writer can heap onto the back of my hero or heroine in a story, the better my story will be.

A mystery-writer friend of mine, Phil Hardwick, says he keeps a note pinned to the wall above his computer that says MAKE THINGS WORSE. “Protagonist” and “antagonist” have agony as part of the words themselves, and we writers should make our main characters feel that pressure right away, and then add to their burdens and hardships at every opportunity. That’s the way to build tension and suspense. Margaret Lucke says, in Writing Great Short Stories, “Pick your protagonist up by the scruff of the neck and fling her headlong into a conflict.”

Bourne again

I’ve probably made this point before, but one of the best examples (of “making things worse”) is Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity. Right off the bat, good old Jason’s in trouble: he wakes up with amnesia. He has no idea who he is or where he is or why he’s where he is (on a freighter in the middle of the ocean). What could be worse than that? I’ll tell you what: he soon finds out people are trying to kill him. He’s alone and hunted and without friends of any kind. What could be worse than that? Well, he then discovers that his own government is trying to kill him. Talk about having a bad day . . .

All of us like to identify with the characters we’re reading about, and if I were in Jason Bourne’s sneakers I might just pull the covers over my head and give up. When likable characters feel pain, we as readers feel their pain as well. When I think of this kind of thing, I always picture Sir Laurence Olivier standing over Dustin Hoffman with a dental drill, saying “Is it safe?”

What’s your dirt doin’ in Boss Kean’s ditch?

Sometimes characters (Martin Brody, Charlie Allnut, Forrest Gump, Will Kane, Frodo Baggins, Rocky Balboa, Clarice Starling, Zack Mayo) make it past their trials and live to fight another day. Others (Ratso Rizzo, Fast Eddie Felson, Shane, Gus McCrae, Randall McMurphy, Vincent Vega) don’t.

Quite often, our fictional heroes’ final failures/misfortunes are heartbreaking. Cool Hand Luke Jackson, after enduring more prison grief than most mortals could handle, finally makes good his escape only to find that another well-meaning inmate has led the Law straight to him. The crew of the Andrea Gail makes the biggest swordfish catch of their lives and are then capsized and sunk by a perfect storm on the way home. The Roman slave Maximus survives countless battles in the arena only to be murdered by a cowardly emperor with the unsavory-sounding name Commodius (or Commodus, depending on which reference you use).

But even those characters who don’t finally succeed do succeed, in a way: they might be dead or disgraced or lobotomized, but they’ve had a profound influence on others in their lives.

Whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger

I like the old problem/complication/resolution saying about story structure. (1) Force man up a tree, (2) throw rocks at man, (3) get man down again. That second item (complication) is just as important as the others. Who wants to see someone with a problem that gets solved easily and immediately?

The bigger and harder the rocks are, the better your story will be.

Good advice, John, but I’d add that you have to be careful not to make the rocks super-sized, because then your character will have to become a superman to escape. That works if your character is a Jack Reacher, Jason Bourne, or a Rambo type but regular people do have limits, even under pressure.

My theory as to the popularity of traditional mysteries is this: when one person is found guilty the reader is found innocent. But then, I was raised Catholic.

1. the puzzle

2. the sense of justice

Thanks for the observations, all of you! And Leigh, you’re right, the puzzle itself is another good reason to read (and write) mystery fiction.

Well…..there are some people who are just plain fascinated with the evil in others and what makes them tick……mainly because it is an unknown side of humanity not understood most.

Maybe I’m a sick puppy. But then I was reared Baptist.