Monday, December 6: The Scribbler

A MAGIC WORD

by James Lincoln Warren

|

Ever wonder why an airtight jar is said to be hermetically sealed? The term hermetic is Greek, and is the adjectival form of the name of the Greek god Hermes, better known to us by his Roman name, Mercury. So you could be excused for assuming that the quality of airtightness, if there is such a word, is somehow associated with a god with wings on his sandals and hat who is the patron of merchants and thieves. Well, sort of.

Another meaning of hermetic is magical, specifically with regard to occult “science”, such as alchemy and astrology. The chemical element mercury had a special place in alchemy, first because it was the only liquid metal, and secondly because a red mineral known as cinnabar, when heated, seems to transform itself into quicksilver, and this was seen as evidence that other substances could be transmuted into gold, one of the aims of the so-called Great Work. So is that where the word comes from? Not exactly.

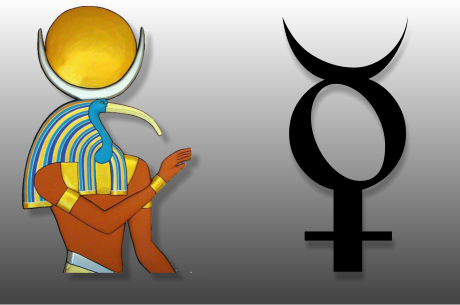

The oldest and longest-lived civilization in Western antiquity was Egypt. As a consequence, they had the oldest gods. One of these was named djhwty, pronunciation unknown but frequently rendered as Djehuty, which roughly translates as “like the ibis.” Ibises are long-legged wading water fowl with long curved beaks. The god “Like the Ibis” was usually depicted as a human male with the head of an ibis. The Greeks transliterated his name from the hieroglyphs, although how exactly is unclear, as Thoth.

Thoth began as a local moon god who through the ages evolved into the Egyptian god of wisdom. As such, he was credited with the invention of writing and of all the arts and sciences. The Greeks of the Neoplatonist school in the Third Century C.E. associated Thoth with their own god Hermes, because the functions the two gods served in their respective pantheons were very similar. Hermes was the god of living by your wits; Thoth the god of wise action. (The Greeks had a separate goddess of wisdom, Athena, and also a god of reason, Apollo, but any similarities with Thoth ended there.) Both were gods of writing and magic. One key job of both gods was to convey the souls of the dead to the underworld.

But to distinguish the Egyptian version from their own, the Neoplatonists added an epigram, Trismagistos, meaning “thrice (tris) great (magistos)”. Nobody knows for certain where the epigram came from, but my favorite theory is that at the temple of Thoth in Esna, an Egyptian city, the god is referred to by another, similar epithet, “the Great, the Great, the Great”, and the Neoplatonists simply shortened it. Orthodox pagans of the 3rd c. did not buy into the conflation of the two gods, however, and so Hermes Trismagistus (as the spelling was permanently Latinized) was usually considered a separate deity.

Thoth was credited with being the author of the oldest text in existence according to Egyptian tradition, the Book of the Dead, because he was the inventor of writing and the arts. This was a tract, or more accurately several tracts (there not being a definitive version), intended to instruct priests on performing funerary rites and mummification. As such, it included several magical spells. And so Hermes Trismagistus became associated with magic.

Somewhere along the line, probably in the middle ages after Paganism had died out, Hermes Trismagistus stopped being considered a god and started to be considered as a wizard, an actual man who had lived in legendary times, and the inventor of alchemy, and the author of the first treatises on magic. Alchemy, of course, is the direct ancestor of modern chemistry, which depends on sublimating and sealing discrete substances. Furthermore, the classical Greeks always placed a small statue of Hermes at the thresholds of the doors of their homes to protect them against thieves, Hermes being the patron god of thieves, thus affecting a sort of seal. And that, O my Best Beloved, is how we got the word hermetic relating to both airtight seals and occult practices, both senses originally being so applied in the 17th c.

(In case you’re wondering, the word magic is not related to magistus. Magic comes from magus, a member of the pre-Zoroastrian priestly caste in ancient Persia, whence we get the Three Wise Men identified as the Magi, and O. Henry’s famous Christmas story.)

So why have I shared this little word journey with the Gentle Reader?

Because the idea of writing has always been inextricably bound with the idea of magic, or at least with miraculous divine acts. It is therefore entirely appropriate that Thoth, the inventor of writing, should also be the patron of magic. The ancient Egyptians believed that the existence of the universe was not possible without writing. The ancient Hebrews had God creating the universe by uttering phrases: “And God said, let there be light, and there was light.” The Gospel According to Saint John opens with “In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and the word was God.”

In a metaphorical sense, they are all correct, because the only way we have of intellectually understanding the universe is through words. Likewise, we fictioneers are doing the most magical of all possible acts by creating worlds of the unreal.

Personally, I have very little patience with anything relating to the occult. I despise astrology and Rosicrucianism and tarot reading and related folderol. There is, however, a real kind of magic in the world, and that is the miracle of language. So crack open that hermetically sealed bottle of champagne and join me in a toast, sipping sweet froth to the honor of Thoth.

Thanks for the words, amigo.

There is, however, a real kind of magic in the world, and that is the miracle of language.

Well said, Jim. And thanks for your words–what a spellbinding narrative!

Wow, Jim. Are you going to begin writing Egyptian historical mysteries? Your whole article (above) was like a well-spun web and I got caught in it by your first few words!

Howdy, Angie. Probably not. The ancient Egyptian mystery is pretty well represented by many excellent authors, beginning with Agatha Christie and continuing through Lynda S. Robinson, P. C. Doherty, I suppose I should include Elizabeth Peters (even though her stories don’t actually take place in ancient Egypt), and a plethora of others. The amount of research required is a little off-putting as well, me not being an Egyptologist like Barbara Mertz, although I do have a long-standing affection for that colorful civilization.

Never say never, though. The one thing I can promise is that if I ever do turn my gaze thither, I will utterly avoid the latter XVIIIth dynasty, especially Tutankhamun and Akhenaton. Too well traveled. What might be interesting is something in Ptolemaic times, when Alexandria was the intellectual capital of the world. That could be fun.

Thank you, Thoth

Ancient Egypt is fun as long as I’m not actually living there! Loved Your words! There’s a “Mammoth Book of Egyptian Whodunnits” available by the way…