Friday, December 31: Bandersnatches

LEAVES FROM THE QUEEN’S NOTEBOOKS

by Steven Steinbock

It’s a new year, and I’d like to start it by launching the first of an occasional series of columns revisiting past issues of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Today we’ll do a retrospective of what you’d find if you opened an issue of EQMM a half century ago.

EQMM began publication in fall of 1941 as a quarterly. Frederick Dannay (half of the “Ellery Queen” persona) served as editor-in-chief until his death in 1982 when Eleanor Sullivan took over. The magazine was originally published by Mercury Press, and then Davis Publications took over in 1958 and continued until Dell/Penny Press bought the magazine in 1992.

An interesting trend in the development of the magazine is the changing ratio of new versus reprint stories. In the early issues, there were usually more reprints of old stories than there were stories that were appearing in print for the first time. In the January 1951 issue, for instance, there are three new stories and six reprints. In the January 1961 issue, there are five new stories and six reprints. By January 1971, the magazine has nine new stories and three reprints, with the word “NEW” in big capital letters on the cover. In the January 1981 issue there are fourteen new stories and one reprint.

The declining number of reprints – and the increasing number of new stories – suggests a number of possibilities:

- Perhaps with the collapse of the pulp magazines, digests like EQMM the biggest venue for new stories;

- The publisher may have had more money to buy more new stories;

- The editor and the readership might have been more inclined to look at new stories than they were at looking back at old ones.

I’m sure there are other possibilities. If you think of any, please put in your two-cents in the Comments section.

It’s important to look back at these old issues, in part because there are some real gems to be found within. But more importantly, the magazine featured the great names in mystery and with rare exceptions, few readers today are familiar with any of them. I’m not just being sentimental or historically romantic. If we don’t keep these names alive, then in another generation readers may forget the names of Lawrence Block, Margaret Maron, Edward Hoch – or you.

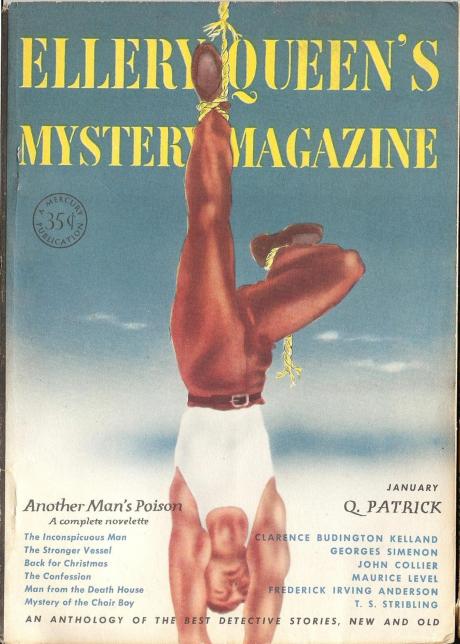

JANUARY, 1951 (vol. 17, no. 86)

The issue features a clever cover design, drawn by George Salter who did most of the EQMM issues of the period. It features a man hanging by his ankle from a shredding rope in the style of the Tarot archetype of the Hanged Man. The opening story is “The Mystery of the Choir Boy” by T.S. Stribling in which, among other things, Dr. Paggioli explains that the word “mystery” should only be applied to unsolvable religious questions. There is “no such thing as a ‘mystery’ in crime,” the psychologist/criminalist explains. “Riddles, perhaps, but not mystery.”

Also included in the issue is an Inspector Maigret story by Georges Simenon, a Barry Perowne story featuring “Digby Gripper,” and a novelette by the Q. Patrick collective.1

Editor Frederick Dannay also challenges the reader with a story called “The Blue Wash Mystery” written by “?” for which Dannay promises $10 cash to the first reader who could identify the author. (Two issues later Dannay revealed that the author was Anna Katherine Green).

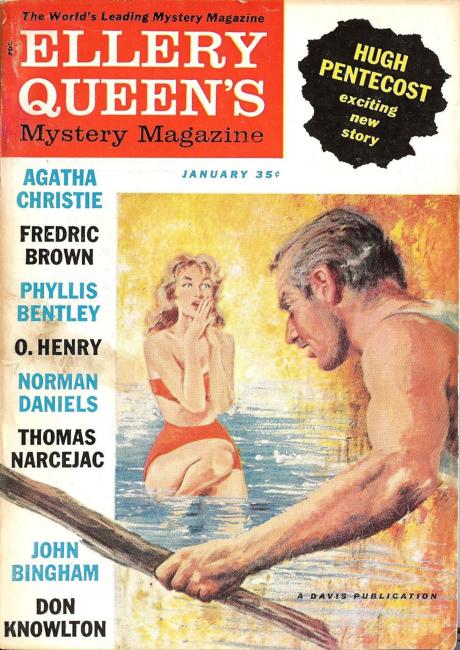

JANUARY, 1961 (vol. 37, no. 1, whole number 206)

The cover features a Gabe Keith depiction of a man with a stick coming toward a blonde in a swim suit, which is supposed to illustrate a scene from the opening story of the issue, “The Man Inside” by Hugh Pentacost. As much as I like the painting, it bears little in common with the story it is illustrating. Yes, there was an angry, unkempt drunk. Yes, there was a lake. But the guy wasn’t drunk when he was at the lake. There was no blonde in a swim suit. It was icy winter at the lake, in fact, and the guy was trying to save the woman, not club her with a stick. But hey, it’s just a picture.

Agatha Christie’s “Never Two Without Three” is a Miss Marple story from The Tuesday Murders (UK title: The Thirteen Problems). Christie’s original title for the story was “A Christmas Tragedy.” It ought to be noted that Fred Dannay was notorious for renaming stories. It didn’t matter how clever or relevant the author’s title might have been, Fred liked coming up with his own titles.

There’s a short off-beat Holmes pastiche in the Department of First Stories written by Jerry Neal Williamson. In this case the expression “off-beat” is especially relevant. It’s a beatnik tale featuring Sheerbach Tones of 221B Basin Street. It’s called “Bopping it in Bohemia.” Cute.

“The Red Orchid” is a Nero Wolfe pastiche written by French crime writer Thomas Narcejac, who was best known for his collaborations with Pierre Boileau (as “Boileau-Narcejac”) that included Les Diaboliques (which was twice translated to film, the better version – a great film, in fact – being Clouzot’s adaptation starring Simone Signoret) and D’entre les morts, which was the basis for Hitchcock’s “Vertigo.”

Fredric Brown, one of my favorite writers, provided the Black Mask Magazine story for the issue.2 “Mr. Smith Protects a Client” features a nebbish insurance agent who – in the style of Lt. Columbo – solves an impossible murder.

The best story in the issue may be “A Retrieved Reformation” by O. Henry. In his introduction to the story, Fred Dannay points out that while not every reader will be familiar with the story, everyone is familiar with the play, the song, the films, and the radio series “Alias Jimmy Valentine” on which this story was the basis. Had you heard of “Alias Jimmy Valentine?” Other than a vague echo deep in my memory, I didn’t know it. First published in 1903, this gem of a tale follows a safe-cracker who tries to settle down to an honest life.

The review section, written by Anthony Boucher, is tiny. Boucher reviews five titles, giving each about twenty words of critique. He gave an Elizabeth Daly novel four stars, and the rest he gave three stars each (including Margaret Millar’s A Stranger in my Grave which I think is a masterpiece). A few other titles are mentioned. But in all there are about 200 words on the page with lots of white space.

The magazine also provided a checklist of new mysteries published that month. There are thirty-four paperbacks (priced between a quarter and fifty cents) and eight hardcovers (all priced at $3.00 or less).

Curious what was in the January issues of 1971, 1981, 1991, and 2001? Hold on to your hats. We’ve got the whole month.

- Patrick Quentin, Jonathan Stagge, and Q. Patrick were three pennames used by a group of four writers. Only Doug Greene and Jon Breen are capable of keeping track of who is what and when. [↩]

- After the pulp magazine Black Mask ceased publication in 1951, Ellery Queen bought the rights to use the name. So beginning in May 1953 EQMM included one or two Black Mask stories in each issue. In 1973, Keith Alan Deutsch bought the name. Then, with the January 2008 issue, EQMM again began printing an occasional Black Mask story. At times these were reprints from the pulp era. But usually they were new stories written “in the Black Mask style.” [↩]

Concerning stories new or old, I believe the market has changed, as well as publishers’ perception of the market.

Publishers prefer to bring out new books and to reprint books only by current authors. For the most part, older mysteries are reprinted only by small houses, and then only selectively. How many readers under the age of 40 have even heard of Anthony

Berkeley, much less read anything by him? Or Clayton Rawson? Or, to use examples from the 1951 EQMM, Clarence Buddington Kelland and Frederick Irving Anderson? Few writers now stay in print after their deaths — are any of Charlotte McLeod’s once very popular books now available in mass market?

Reading tastes have changed. The days of popular general-interest magazines providing fiction are over. The hey-day of The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s and Liberty Magazine is long-gone. The demographics of the reading public has also changed. Now over 70% of all fiction is read by women; in the eyes of publishers, they demand a style and content different from that of the past. Most stories today seem more to be crime stories than the pure deductive mystery tale.

The field has also matured. There’s more emphasis on characterization (as opposed to characters) and on social issues (large and small). Excellent work is being done today, but I truly doubt few stories from the current EQMM would ever have been printed in the old EQMM.

What a wonderful idea to recap some of the old EQMM issues! Hope to see more!

Happy New Year!

Jeff, I certainly intend to repeat this kind of column. I glad you enjoyed it.

Jerry, I like your observations about the changes in reading and publishing habits. In particular, your comment about gender and reading demographics makes a lot of sense. My guess is that women have always dominated reading. But in the 1940s through the 80s, publishers ignored that fact. But if you look at the contents of EQMM today (or at any period in its history), I think you’ll see that the fiction transcends gender.

Absolutely fascinating – more, please!

boy, that 1961 cover was a shock. Looked like Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine instead of what I expect from EQMM. Give us more, Steve.