Tuesday, August 5: High-Heeled Gumshoe

Melodie asked previous Criminal Brief contributor and award-winning journalist Kathleen Sharp to fill in for her today. Melodie should be back next week. —JLW

by Kathleen Sharp

Parody is on life support and I’m holding a vigil. What prompted this is the recent emotional reaction to a few mild-mannered stabs at political humor. The New Yorker put Barack Obama and his wife, Michelle on its cover. Historically speaking, it was a weak attempt at satire. Obama and his wife were depicted in Muslim garb, giving each other an Islamic knuckle-salute. I thought the New Republic’s cover was funnier. It showed John McCain in a wheel-chair being given his daily meds by grinning wife Cindy. But that cartoon didn’t get as much traction as McCain’s TV ad, which compares the Democratic candidate to celebrity air-heads Britney Spears and her twice-removed cousin Paris Hilton.

Parody is on life support and I’m holding a vigil. What prompted this is the recent emotional reaction to a few mild-mannered stabs at political humor. The New Yorker put Barack Obama and his wife, Michelle on its cover. Historically speaking, it was a weak attempt at satire. Obama and his wife were depicted in Muslim garb, giving each other an Islamic knuckle-salute. I thought the New Republic’s cover was funnier. It showed John McCain in a wheel-chair being given his daily meds by grinning wife Cindy. But that cartoon didn’t get as much traction as McCain’s TV ad, which compares the Democratic candidate to celebrity air-heads Britney Spears and her twice-removed cousin Paris Hilton.

I thought the ad itself was mildly entertaining. But no one else I know did. Instead, these works have apparently triggered a national firestorm about what is fair, right and decent in politics.

When did we lose our Yankee humor?

Satire and parody have been a proud American tradition since the days of George Washington. Our very first President was ridiculed in an 18th Century cartoon that showed him on a donkey led by his aide, David Humphrey. It read:

The glorious time has come to pass

When David shall conduct an ass.

(You had to be there.) President Garfield was once depicted as a fat, unwed mother in a really tight dress. Ulysses S. Grant was lampooned as an incompetent drunk and Grover Cleveland was caricatured as a brothel-lover.

Going back to the 1700s, our press was born of outrage with equal parts piss and vinegar. Our then-British rulers feared that newspapers would fan political opposition. So, they clamped down on the press. They tried to use the Stamp Act of 1765 to restrict the broadsheets and pamphlets that stirred our revolutionary zeal. The whole “taxation without representation” fell on the media and without good press, the tax utterly failed.

By 1790s, the Federalist papers gleefully traded barbs and insults with the Republican ones. Parody, satire and nasty-grams were as common as ham-and-eggs. Political humor was fall-down funny. Anyone around here remember that scandal involving our nation’s first U.S. Treasurer, his lover and her husband? Editors couldn’t stop the running gags about Alexander Hamilton.

During the American Revolution, the press helped spread populist ideas. Thanks to cheap newspapers, cheaper postage and free schools everyone was included in the national conversation, from the hinterlands to the cities. That meant that everybody could take part in public and political life. There was a shared sensibility for ribald humor and sick jokes. And this was due in large part to the world’s first mass-circulation press.

U.S. publishers developed a tradition of bare-knuckled, balls-to-the-wall tactics. They wrote lurid headlines and stories with wild accusations without bothering to verify the facts—sort of like what most TV and radio “reporters” do today. But the difference was that reporters and cartoonists back then came from the working class. They got their leads and humor from the street, the tavern, the courtroom, the precinct. Sure, there was a lot of mediocre talent and false stories. But there was also passion, and I’m not just talking of politics. One broadsheet from the 1800s regularly published mild-mannered erotica, like this passage from 1800s: “He devoured my fine pink silk stockings in a frenzied gaze impossible to describe. He began to whisper indecencies. I replied with suggestions even more lewd.” Perhaps this was a parody of lust. But either way, the mainstream press had a wicked streak that I’d like to revive.

U.S. publishers developed a tradition of bare-knuckled, balls-to-the-wall tactics. They wrote lurid headlines and stories with wild accusations without bothering to verify the facts—sort of like what most TV and radio “reporters” do today. But the difference was that reporters and cartoonists back then came from the working class. They got their leads and humor from the street, the tavern, the courtroom, the precinct. Sure, there was a lot of mediocre talent and false stories. But there was also passion, and I’m not just talking of politics. One broadsheet from the 1800s regularly published mild-mannered erotica, like this passage from 1800s: “He devoured my fine pink silk stockings in a frenzied gaze impossible to describe. He began to whisper indecencies. I replied with suggestions even more lewd.” Perhaps this was a parody of lust. But either way, the mainstream press had a wicked streak that I’d like to revive.

In 1841, a guy named William J. Snelling started a weekly called The Flash and printed gossip about theater groupies, politicians and sporting events. The Flash encouraged white-collar “sporting men” to defy America’s upper-class moral values by mingling with people of different races, classes, and nationalities. His paper was so popular that it spawned competitors such as The Whip, The Libertine and The Rake.

In 1841, a guy named William J. Snelling started a weekly called The Flash and printed gossip about theater groupies, politicians and sporting events. The Flash encouraged white-collar “sporting men” to defy America’s upper-class moral values by mingling with people of different races, classes, and nationalities. His paper was so popular that it spawned competitors such as The Whip, The Libertine and The Rake.

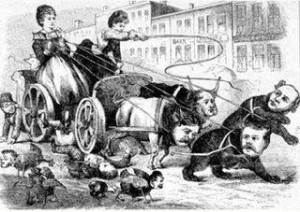

Women jumped into the publishing fray, too. Victoria Woodhull, a woman’s suffragette who advocated free love, and her sister, Tennesee Claflin, the first female broker on Wall Street, were so controversial, they were often ridiculed. One cartoonist at The Day’s Doings showed the two babe-alicious sisters running their brokerage firm like half-naked harlots. The male car- toonist tried to equate independent females with sexually wanton women. Instead, he just encour- aged more suffragettes to unlace their bodices and go to work.

babe-alicious sisters running their brokerage firm like half-naked harlots. The male car- toonist tried to equate independent females with sexually wanton women. Instead, he just encour- aged more suffragettes to unlace their bodices and go to work.

Half-a-million readers lapped up the weekly political cartoons of the Daily Doings. At one point, the sisters Woodhull and Clafin got so tired of being lampooned, they started their own newspaper. But instead of funny pictures, they printed mostly investigative stories about powerful, mysterious men.

Things purred along nicely until New York district attorney James Whiting used the law to haul Snelling and others into court. Woodhull and her sister were charged with obscenity for publishing a true story about an adulterous preacher. A jury set them free, but not before they spent days in a cold jail cell. Other publishers were charged with libel and obscenity and endured longer sentences. In time, several pioneering newspapers were forced to fold. Nobody laughed. Snelling got out of jail, become a serious prison reformer and went on to edit the then-respectable Boston Herald. But he never had as much fun. He died penniless and humorless, a pillar of the Brahmin community. His ending wasn’t very funny.

But in reviewing our republic’s history of humor, I daresay I know what is fair, right and decent about political parody. Nothing.

A few of those early political cartoonists stick with us, perhaps Thomas Nast being the most famous, following the Civil War.

Lincoln himself was a major target of political cartoonists, often from factions within his own party including the Whigs and Know-Nothings. I picture him resignedly sighing and folding– not wadding– the paper for his fireplace.

Editors as well as cartoonists shaped our historical perceptions. Jesse James comes to mind as an example.

After your description of The Flash, I wonder if there was a not-so-accidental wink toward Flashman? Probably not, but it’s interesting to speculate.

Here in Florida, prosecution is used as a heavy-handed weapon against everything from ‘adult’ stores, ‘adult’ clubs, ‘adult’ publications, and in one case a south Florida amateur cartoonist who photocopied his hand-drawn ‘comix’ for dissemination among friends. Prosecutors cheerfully admit that cases they manage to win are likely to be overturned on appeal– if the

victim, erdefendant can afford the legal fees, which they usually can’t. It’s ruling by financial attrition.As a whole — and in my humble opinion –America has lost its sense of humor. Parody and satire are supposed to make one smile first, think later. SNL and The Daily News are comedy shows, not news reports. Me thinks we think too much and read way too much into things meant only to give us a nudge, nudge, wink, wink. Can’t we all just get along? BTW, great article!

Great article.

I agree that we’ve lost our sense of humour unless it is “politically correct” to think funny.

Off-topic: The New Yorker Obama cover overshadowed the cover the following week. Look it up, it’ll make you smile. Especially if you’ve worked at a seafood restaurant (and I have!)