Monday, September 10: The Scribbler

VERY LITTLE BRAIN

by James Lincoln Warren

A golden thread among all our contributors in the past week is the importance of exposing children to reading. The trend continues herewith, although being me, I’m taking the opportunity to bitch a little.

J. R. R. Tolkien once made a remark to the effect that a children’s book is not a good children’s book unless it can be read and enjoyed by an adult. I concur.

I love good children’s books and among my all-time favorites are the works of A. A. Milne. I still treasure the battered copies of Winnie-the-Pooh and The House at Pooh Corner that my mother read to me when I was a pre-schooler. (“Property of Jimmy W.” is proudly if unevenly inscribed on the front flyleaf of the latter.)

I was lucky. I grew up as part of a generation that knew Pooh before the Disney company got its hands on it.

Disney perverted Pooh. They took the Bear of Very Little Brain with a growly voice and a penchant for charming doggerel and turned him into a fat insipid yellow marshmallow voiced by Sterling Holloway (whose voice does not remotely growl) with a penchant for Mr. Rogers-style songs of cloying sweetness. The kittenishly rambunctious Tigger somehow acquired American ventriloquist Paul Winchell’s voice and wound up resembling a Borscht Belt pratfall comedian.

Disney perverted Pooh. They took the Bear of Very Little Brain with a growly voice and a penchant for charming doggerel and turned him into a fat insipid yellow marshmallow voiced by Sterling Holloway (whose voice does not remotely growl) with a penchant for Mr. Rogers-style songs of cloying sweetness. The kittenishly rambunctious Tigger somehow acquired American ventriloquist Paul Winchell’s voice and wound up resembling a Borscht Belt pratfall comedian.

I have nothing against the dedicated and gifted Fred Rogers, nor against those fearless vaudeville comics who provided us with tears of laughter in their later incarnations as Hollywood slapstick artists. But let’s face it — they are categorically out of place among the innocently wise denizens of the Hundred Acre Wood.

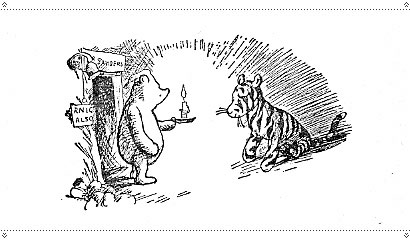

All children in the English-speaking world, and multitudes of children born to other native languages, know about Pooh. But which one? A lot was lost in translation when he made the jump from being a literary lion, uh, bear, to being a star of the silver screen. Even on the most basic visual level. Compare Ernest Shepard’s image of the rotund teddy bear and his feline friend above with the Disney version below it.

Shepard’s illustration, with its candle in the dark, Pooh’s nightcap, and timorous stuffed tiger, clearly belongs in a book, where it can be carefully scrutinized, the images poised tantalizingly on the edge of the juvenile imagination — What’s in the dark? Why does (the usually enthusiastic) Tigger look so scared?

The Disney illustration, by contrast, looks like a commercial print on a child’s bedsheet: something to be urinated on. Stock sunshine and plasticized flowers and a pillowy Pooh, who has somehow acquired a baby T-shirt that oh-so-preciously fails to cover his infantile belly (although in fairness, Shepard does occasionally portray Pooh as wearing a too-small short jacket in cold weather, an obvious reference to Pooh’s predilection to eat more than he ought), tout ensemble accentuating a revolting neotenous cuteness (whither proud Edward Bear?), in tandem with a slack-jawed, idiotically grinning Tigger, and no mystery nor wonder whatsoever — there’s absolutely nothing present to stimulate a child’s internal creativity.

It’s predigested, processed, packaged, and presented like a corporate Power Point slide. It’s the post-literate Pooh, the Pooh for an era when the very existence of children’s toys depends on tie-ins to TV shows and manufactured action figures and mass marketing.

The first time I heard of the Shepard illustrations referred to as “classic Pooh”, obviously in contrast to the animated “standard” Pooh, I nearly lost my lunch. The Disnified Version is only standard if you have no standards at all.

And what, the Gentle Reader may ask, has this to do with mystery short stories?

Aside from the fact that the Winnie-the-Pooh books are essentially short story collections — every chapter represents a separate adventure in the lives of the toys and animals populating Winnie-the-Pooh’s benign fairy-tale tinted wilderness — another answer is that kids’ books set the stage for what people read later in life: good taste is acquired through early and consistent exposure to good things. Yet another salient factor is that good children’s literature has a lot in common with good short story writing, in that economy of expression is a crucial element of quality. One of the best things about A. A. Milne is his whimsical prose. Consider Rabbit’s nefarious eleven-point program for kidnapping Baby Roo (I told you Pooh was relevant to crime fiction):

PLAN TO CAPTURE BABY ROO

1. General Remarks. Kanga runs faster than any of Us, even Me.

2. More General Remarks. Kanga never takes her eye off Baby Roo, except when he’s safely buttoned up in her pocket.

3. Therefore. If we are to capture Baby Roo, we must get a Long Start, because Kanga runs faster than any of Us. (See 1.)

4. A Thought. If Roo had jumped out of Kanga’s pocket and Piglet had jumped in, Kanga wouldn’t know the difference, because Piglet is a Very Small Animal.

5. Like Roo.

6. But Kanga would have to be looking the other way first, so as not to see Piglet jumping in.

7. See 2.

8. Another Thought. But if Pooh was talking to her very excitedly, she might look the other way for a moment.

9. And then I could run away with Roo.

10. Quickly.

11. And Kanga wouldn’t discover the difference until Afterwards.

You can’t deny that you actually have to read this in order to fully appreciate its wit. It’s not the sort of humor that you can portray in an animated cartoon. One who reads such a passage will have a higher expectation of what can and should be done in good writing. Gaining knowledge of this simple fact, that you really have to read a story to get everything it has to offer, is central to encouraging people, and not just little people, to read. It’s precisely why Criminal Brief has our Instant Reviews section (which, I might observe, has a new review by Rob Lopresti of a story by Kevin Wignall, who will be featured as a Mystery Masterclass contributor soon). It’s the reason why so many people are so bitterly disappointed in film adaptations of their favorite written works. It’s why we go back and read our favorite stories again and again and again.

And having learned the delight of reading good stuff, we gain the profitable skill of being able to recognize poo when we smell it.

Plug Dept.

I will be moderating a panel, DARK PAST: THE HISTORICAL CRIME NOVEL, featuring Aileen G. Baron, Cordelia Frances Biddle, Gay Kinman, and Michael Mallory, at the West Hollywood Book Fair between 12:15 pm and 1:15 pm on Sunday, September 30. Please drop in to hear what we have to say (after short mystery fiction, my great passion, predictably, is historicals) and to say hello. Although the title of the panel indicates that it is restricted to the novel, trust me, we’ll be getting in a few shots regarding short fiction as well, if I have anything to say about it (and I do).

Note: By 2000, Pooh had become Disney’s most popular character, exceeding the popularity of even Mickey Mouse.

I remember, in probably second grade, sitting down with a notebook and trying to write an additional Pooh story. Probably the first time I ever tried to write something. Got nowhere, of course, but I owe that first attempt to Milne.

Great piece. Additional relevance to the purpose of the blog: Milne was also an adult mystery writer, with numerous short stories and the novel THE RED HOUSE MYSTERY (1922) to his credit.

Thank you! Your comments are all too true.

When the first of the despicable Disney Version cartoons came out, I planned to avoid it — but my mother tricked me into taking a young out-of-town visitor. It took me years to forgive her. And although my children own a heap of Disney movies, their vile version of Pooh has never crossed our door.