Monday, September 8: The Scribbler

READERS OF THE LAST ARC1

Considering the Storyline Diagram, Part the First

by James Lincoln Warren

One of the wonderful things about running a rotating blog is the gift of inspiration from distinguished colleagues. John wrote about story arcs a couple days ago, and that simple act has stimulated me to write this column, the subject of which has been lurking in the back of my brain for months.

To a bookseller, an ARC is an “Advance Reader’s Copy”; i.e., a paperbound uncorrected proof or galley. These are given by publishers to bookstores in hopes that the staff will read them and recommend them to customers. (The exception to this is the ARC by a bestselling author, which is offered as a kind of candy to the bookseller.) These ARCs are usually virtually identical to the finished book—the only corrections required are usually by way of typographical and formatting errors. So the reader does not really get much of an insight into the process the book goes through as it evolves from concept to product. It’s the literary equivalent of a Hollywood sneak preview screening.

To a bookseller, an ARC is an “Advance Reader’s Copy”; i.e., a paperbound uncorrected proof or galley. These are given by publishers to bookstores in hopes that the staff will read them and recommend them to customers. (The exception to this is the ARC by a bestselling author, which is offered as a kind of candy to the bookseller.) These ARCs are usually virtually identical to the finished book—the only corrections required are usually by way of typographical and formatting errors. So the reader does not really get much of an insight into the process the book goes through as it evolves from concept to product. It’s the literary equivalent of a Hollywood sneak preview screening.

To an writer, the word “arc” means something very different. The word is used to describe the structure of a story, perhaps in allusion to the parabolic arc of a ballistic trajectory, with which it has some things in common. Like most such terms, its application is very fluid. In television, for example, it generally means a long story line over several episodes rather the plot of a single episode. In screenwriting courses, it almost always is a synonym for three-act structure. Now, I have a serious confession to make.

I’m a heretic.

You see, I don’t believe in the three-act structure.

That’s not to say that I don’t believe in its existence. That would be very hard to do given how many scribes crank out screenplays using it as a holy template. I just don’t believe that it’s the archetypal story format everybody seems to think it is.

As long as I’m in an unbosoming mood, I should also own up to generally viewing screenwriting seminars with a lemony-bright jaundiced eye—to be frank, I’m suspicious of all creative writing courses, even though I have many friends who teach them (three of them here on Criminal Brief alone) and other friends who swear by them, all writers for whom I have unbounded respect. So please, Gentle Reader, don’t get upset by what’s next, because the following opinions are my own and not meant to apply to others.

There are two poles in creative writing instruction. On the one hand, there are those lessons that are meant to inspire the writer and engage his powers of creativity. These usually involve writing exercises, something I consider a waste of time. How can you teach someone to have an imagination? On the other hand, there are composition classes that teach narrative and rhetorical techniques. These usually involve critical reading of effective writing. I’m not quite as hostile to this approach, but I can’t see how any serious writer needs to be taught how to read, either. After all, as Canadian poet Eli Mandel famously observed, “When he looks back, the critic sees a eunuch’s shadow.”2

Most courses fall somewhere between these extremes by trying to inspire students by imparting, for a fee, the Secrets of Success. Of these curricula, many depend on the verve and personality of the instructor, a sort of Cult of Creative Personality. One of the most admired of these gurus is Syd Field, who is generally credited with originally having the three-act insight, a screenwriting Moses bearing the Screenplay Commandments. Well, I’m sorry, John and Steve, but I think Syd Field is a charlatan. (If you doubt me, do an IMDB search on his screenwriting credits.)

Hasn’t Syd Field been [“a screenwriting know-it-all”] … for nearly three decades, squeezing precious dollars out of starry-eyed wannabes? When I first got the bug, I pored over his book “Screenplay.” I was rapt during his workshops as he revealed precisely where each turning point in our plots must be placed if we were to succeed as he had. Then, one day, I got a look at a few pages of one of Syd’s unproduced scripts, set in the world of race-car driving. The characters were as wooden as Pinocchio, the dialogue as flat as Olive Oyl. I decided to ask Syd, who was fond of promoting himself as a successful screenwriter, about his movie credits, and I got plenty of evasion but no titles.

—John Morgan Wilson3 in the Los Angeles Times, March 12, 2006

This not to say that three-act structure doesn’t rule, because it does. All I’m saying is, it’s a damn shame, because as models go, it is extremely inflexible. At a writers luncheon not long ago, I sat with two screenwriting consultants and I asked them whether the use of three-act structure was required. Their short answer was YES, and I was circling in for the kill when they were rescued by Jan Burke, sitting on my left, who said, “Jim, I use three-act structure.”

There was no recovering from that, since she’s one of the very best writers I know. But I nevertheless continue to believe that (a) three-act structure does more harm than it does good (especially in the hands of less gifted writers than Jan), and (b) three-act structure itself is nothing but a special case of the venerable and much more versatile storyline diagram.

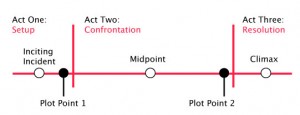

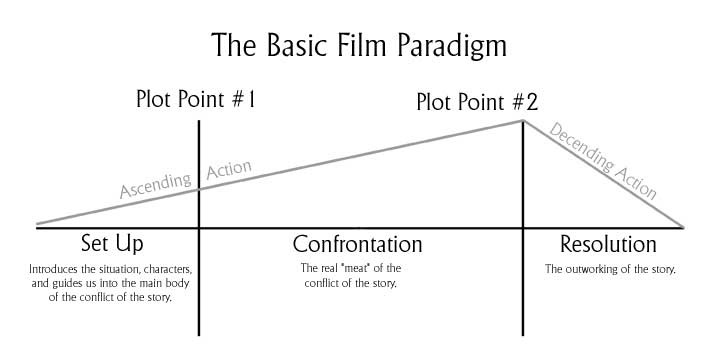

A few weeks ago, Steve provided these two diagrams showing Field’s vaunted structure:

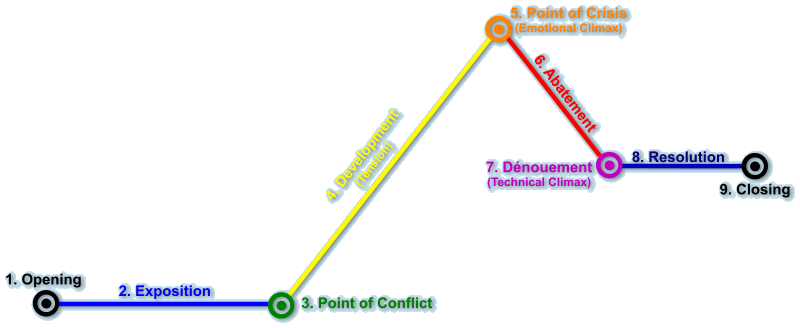

Here is a modified4 version of the storyline diagram I was taught way back during the Bronze Age, courtesy of my Twelfth Grade Honors English class in 1972. (Thank you, Mrs. Mullen). Click on the image to enlarge it.

As you can observe, they are similar but not identical. The story diagram is simpler and more specific. Field’s diagrams also do not designate an essential part of the three-act paradigm, viz., that at the end of Act Two, the protagonist is at his lowest ebb, only to triumph against all odds in Act Three. This can be a nice plot twist; I’ve used it myself. But it isn’t absolutely essential to a good story.

There are nine elements in the storyline diagram: Opening, Exposition, Point of Conflict, Development, Point of Crisis, Abatement, Dénouement, Resolution, and Closing. Here’s how they are defined.

1. Opening. A statement or action designed to engage the reader.

2. Exposition. Narrative that provides all the information necessary for the reader to understand the ensuing action.

3. Point of Conflict. An incident or situation which initiates the principle action; a circumstance or discovery that requires the participation of the protagonist to be resolved.

4. Development. The deliberate and incremental increase of the tension initiated by the Point of Conflict.

5. Point of Crisis or Emotional Climax. A singular point of unsustainable tension upon which the principle action pivots.

6. Abatement. The release of tension.

7. Dénouement or Technical Climax. The point at which the principle action is resolved or its effects finalized.

8. Resolution. Narrative that serves to restore the status quo or to establish a new equilibrium.

9. Closing. Narrative that serves to signal completion of the action.

Some stories do not require all nine of these elements, and other stories may combine certain elements into a single point, especially Point of Crisis and Dénouement, likewise Resolution and Closing. There can also be more than one iteration of a specific element—more than one emotional climax, for example (although I’d argue there can only be one overriding Point of Crisis, beside which all others pale). The point is that the diagram can be twisted about to accommodate the author’s design as long as it sustains its essential shape— not all of the exposition, for example, has to come in the beginning, nor must all of the action explicitly follow the Point of Conflict, but the wave-like rise and fall of the storyline’s shape should remain more or less intact.

Next week I’ll give some examples of how the diagram and its components can be modifed, mixed, and matched.

For now, I will leave the contemplation of the diagram to the reader as an exercise in meditation, with the admonition that a model is only a means to improve comprehension and should never be confused with the actual thing it models. A storyline is not a story. Thereby lies madness, or at least crappy and unimaginative writing. But insofar as models make things easier to understand, being familiar with this one may benefit readers and enhance enjoyment in reading.

But I do have much more to say on the subject, if the Gentle Reader will kindly indulge me.

- I usually hate cutesy wordplay in titles, but in this instance I simply could not resist. Forgive me. [↩]

- Mendel used the phrase in his essay “The Poet as Critic” in 1977. I have also seen this quote, or one almost identical to it, attributed to polymath George Steiner. The sentiment, however, probably originated with Irish author Brendan Francis Behan (d. 1964), who observed, “Critics are like eunuchs in a harem; they know how it’s done, they’ve seen it done every day, but they’re unable to do it themselves.” [↩]

- Winner of the Edgar Award for Best First Novel by an American Author in 1997 for Simple Justice and a friend of mine. He now writes mostly for documentary crime television shows, although he continues to chronicle the exploits of Benjamin Justice, a gay HIV-positive private detective. John, like our own John M. Floyd, Deborah Elliott-Upton, and Melodie Johnson Howe, also teaches creative writing, through the UCLA Extension Writers’ Program. [↩]

- I have added the “Opening” and “Abatement” labels, relabeled “Climax” as “Point of Crisis”, relabeled “End” as “Closing”, displayed plot points as circles instead of simple vertices on the line, and color-coded the elements for clarity. [↩]

Wow! Somebody should have told me I needed to know all this stuff about 40 years ago. Old dogs and new tricks seldom go well together.

Dick Stodghill doesn’t need to be taught how to write a story any more than Woody Guthrie needed to be taught how to write a song. I can, however, show you lots of song-writing seminars that hint they can teach you how to be Woody Guthrie.

It is a truism that theory follows practice. Beware!

To trope on a comment in the text, a story isn’t a storyline, either. Not only are three-act structure and storyline diagrams not magic bullets, they’re not even ammunition. They may, however, be used as targets, as long as you remember that target shooting is only practice.

Wonderful read, feel as if there is a venerable lecturer at the front of the room. Good stuff to ponder about–and review in my own writing. Had an author teach that each chapter in mystery writing had to have its own conflict, crisis and conclusion, however benight. And these build in kind and intensity to the denouement with the traditional trailing off to the trailing off, if you will to the resolution and closing.

Very enjoyable read!

Pat Harrington

Always enjoy it when more than one person here posts on the same subject. Different points of view work (at least they do here!) What? More on this topic? How about titling it “ARC Of The Covenant” or “Raiders Of The”—-no! no! I won’t say it!!!

don’t teach through UCLA anymore. I do teach at The Santa Barbara Writers Conference.

I think a good teacher can help a talented student writer, but more as an editor than a pontificating teacher. The important word here is “good”. I also think a talented writer who doesn’t have the strength of his convitions can be hurt. But part of being a good writer is developing that strength.

If the student is not talented then teaching is a process in getting the best you can.

Anything that has to be diagramed is not writing. It’s busy work.

The third act? Well as with most creative things it works when the writer needs it and it doesn’t work when it’s not needed. Many plays are two acts now. The very act Fitzgerald thought most Americans didn’t have in them. The point?

Write and forget the pie charts. They give me a headache.

Great column. I appreciate how you took Field’s Three-Act theory down a few notches, even though I discussed it a few weeks back.

My only disagreement is with your two poles in creative writing instruction. To me, the two poles are Roman Polanski and Jerzy Kosinski.

Good article. I look forward to the next.