Thursday, September 11: Femme Fatale

OH, HENRY!

by Deborah Elliott-Upton

Ask readers why they remember the stories of O. Henry and it’s likely due to his surprise endings. It could also be that he wrote approximately 600 stories, publishing at least one a week during the ten year span while living in New York City until his death. As in his stories, his life revealed one last ironic twist: acclaimed as America’s favorite short story writer, he died a penniless alcoholic at the age of 48.

Ask readers why they remember the stories of O. Henry and it’s likely due to his surprise endings. It could also be that he wrote approximately 600 stories, publishing at least one a week during the ten year span while living in New York City until his death. As in his stories, his life revealed one last ironic twist: acclaimed as America’s favorite short story writer, he died a penniless alcoholic at the age of 48.

“The Rue Chartres, in New Orleans, is a street of ghosts. It lies in the quarter where the Frenchman, in his prime, set up his translated pride and glory; where, also, the arrogant don had swaggered, and dreamed of gold and grants and ladies’ gloves. Every flagstone has its grooves worn by footsteps going royally to the wooing and the fighting. Every house has a princely heartbreak; each doorway its untold tale of gallant promise and slow decay.” —from “Blind Man’s Holiday” by O. Henry

O.Henry’s endings are memorable, but his choices of opening paragraphs are also intriguing, easily hooking the reader in like hungry catfish on a hot summer’s day.

“The most notable thing about Time is that it is so purely relative. A large amount of reminiscense is, by common consent, conceded to the drowning man; and it is not past belief that one may review an entire courtship while removing one’s gloves.” —opening paragraph of “The Cactus” by O. Henry

While the courtship dance takes place between the two main characters in “The Cactus,” O. Henry describes how the manly Trysdale yields to vanity and conceit in accepting the label as one fluent in Spanish when in fact, he had merely quoted a Castilian proverb he’d found at the back of a dictionary. When friends admire his knowledge of the language in front of the lady he is attracted to, he feigns agreement by not protesting. In this way, O. Henry prepares the stage of events to follow when pride overshadows commonsense.

While the courtship dance takes place between the two main characters in “The Cactus,” O. Henry describes how the manly Trysdale yields to vanity and conceit in accepting the label as one fluent in Spanish when in fact, he had merely quoted a Castilian proverb he’d found at the back of a dictionary. When friends admire his knowledge of the language in front of the lady he is attracted to, he feigns agreement by not protesting. In this way, O. Henry prepares the stage of events to follow when pride overshadows commonsense.

“I will send you my answer tomorrow,” she said; and he, the indulgent, confident victor, smilingly granted the delay. The next day he waited, impatient, in his rooms for the word. At noon her groom came to the door and left the strange cactus in the red earthen jar. There was no note, no message, merely a tag upon the plant bearing a barbarous foreign or botanical name. He waited until night, but her answer did not come. His large pride and hurt vanity kept him from seeking her.

While Trysdale waits for her to answer, she, too waits expectantly. When neither makes a move, the moment seems to be lost. O. Henry carefully paces the story, leaving the last line to reveal to the reader and Trysdale the cruel truth: the Spanish words she’d written on the plant’s tag translate “Come and take me.”

In “Blind Man’s Holiday,” Lorison is an “everyman” whom readers universally can relate.

“You do not understand,” said Lorison, removing his hat and sweeping back his fine, light hair. “Suppose she loved me in return, and were willing to marry me. Think, if you can, what would follow. Never a day would pass but she would be reminded of her sacrifice. I would read a condescension in her smile, a pity even in her affection, that would madden me. No. The thing would stand between us forever. Only equals should mate. I could never ask her to come down upon my lower plane.” —from “Blind Man’s Holiday” by O. Henry

O. Henry was born in Greensboro, North Carolina with the name, William Sydney Porter, on his birth certificate. His mother died when he was three years old and his physician father, Algernon Sidney Porter, left his care to his own mother and Great Aunt Lina, who schooled the avid reader. William left her school at fifteen and worked in his uncle’s pharmacy and became a licensed pharmacist. He was known for his cartoons featuring the citizens of his hometown. At twenty, he moved to Texas for health reasons and worked on a sheep ranch in LaSalle County for two years, living with the family of Richard M. Hall, close friends of the Porter family in North Carolina. In 1884, he moved to Austin and for three years lived in a room with the Joseph Harrell family.

By 1887, Porter had married and worked as a draftsman in the General Land Office, headed by his friend Richard Hall. In 1891 when Hall’s term at the Land Office expired, he resigned and became a teller at the First National Bank in Austin. After a few years, Porter left the bank and founded The Rolling Stone, a weekly humor magazine. The magazine’s circulation was not as profitable as hoped and its editor began drinking heavily. When it finally folded, Porter began writing a column for the Houston Daily Post.

By 1887, Porter had married and worked as a draftsman in the General Land Office, headed by his friend Richard Hall. In 1891 when Hall’s term at the Land Office expired, he resigned and became a teller at the First National Bank in Austin. After a few years, Porter left the bank and founded The Rolling Stone, a weekly humor magazine. The magazine’s circulation was not as profitable as hoped and its editor began drinking heavily. When it finally folded, Porter began writing a column for the Houston Daily Post.

Several years before, Porter had worked for the First National Bank in Austin. The bank now accused him of having embezzled funds during his employment there. Fearful, Porter left behind his wife and young daughter and fled first to New Orleans, then Honduras. When news reached him that his wife was extremely ill, he returned to America, only to find her close to death. After her death, he stood trial on the embezzlement charge. Found guilty, he was sentenced to five years and shipped off to a penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio. Whether he was truly guilty has never been proved and there has been much speculation as to the truth. Released after three years, Porter emerged with a handful of short stories written while he’d been incarcirated in attempts to provide for his motherless daughter.

During this time, William Porter decided to create a pen name for himself. There are several rumors concerning the pseudonym’s origination. One is from his frequently calling, “Oh, Henry!” when looking for the family cat. Another story suggests it was used more as a disguise following the scandal of his arrest and the prison term he’d served.

As all writers are apt to do, O. Henry used his first-hand experiences in New York and Texas to write believable scenarios. In 1907, he published many of his Texas stories in The Heart of the West, a volume that includes “The Reformation of Calliope,” “The Caballero’s Way,” and “Last of the Troubadours” —a story proclaimed by J. Frank Dobie (another highly acclaimed Texas writer) as “the best range story in American fiction.”

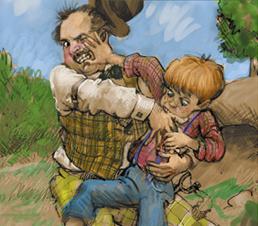

One of my favorites is “The Ransom of Red Chief”, where O. Henry has been compared to Mark Twain as a humorist. It is one of O. Henry’s most popular stories, featured in many anthologies.

In the story, two men down on their luck decide to kidnap the child of a well-to-do man in town. Little did they realize trouble sometimes masquerades as a simple plan wrapped around a child’s supposed innocence. The boy claims his name is Red Chief and the men play along in an attempt to make the task of the crime easier.

In the story, two men down on their luck decide to kidnap the child of a well-to-do man in town. Little did they realize trouble sometimes masquerades as a simple plan wrapped around a child’s supposed innocence. The boy claims his name is Red Chief and the men play along in an attempt to make the task of the crime easier.

Just at daybreak, I was awakened by a series of awful screams from Bill. They weren’t yells, or howls, or shouts, or whoops, or yalps, such as you’d expect from a manly set of vocal organs – they were simply indecent, terrifying, humiliating screams, such as women emit when they see ghosts or caterpillars. It’s an awful thing to hear a strong, desperate, fat man scream incontinently in a cave at daybreak. I jumped up to see what the matter was. Red Chief was sitting on Bill’s chest, with one hand twined in Bill’s hair. In the other he had the sharp case-knife we used for slicing bacon; and he was industriously and realistically trying to take Bill’s scalp, according to the sentence that had been pronounced upon him the evening before. I got the knife away from the kid and made him lie down again. But, from that moment, Bill’s spirit was broken. He laid down on his side of the bed, but he never closed an eye again in sleep as long as that boy was with us. —from “The Ransom of Red Chief”

During his life, O. Henry published 10 collections and over 600 short stories. Although he wrote prolificly, his personal life was in shambles. He remarried in 1907, but his drinking two quarts of whiskey a day on average didn’t help his marriage or his writing. He died of cirrhosis of the liver on June 5, 1910, in New York. Following his death, three more collections of his work were published. Sixes and Sevens appeared in 1911; Rolling Stones in 1912 and Waifs and Strays in 1917. In 1918, the O. Henry Memorial Awards were established. The award is presented annually to the best magazine stories with the winners to be published in an annual volume.

I always wonder if such a life hindered or created the writer’s career. Surely his many travels and jobs helped him write of those situations and settings. But, did his life style choices and circumstances enhance his writing? Would O. Henry’s tales have been as memorable without the heartaches of losing his wife and his freedom or did those experiences add to his ability to write the stories he did?

I’ve often wondered this about many authors.

Good article.

Yes, it is a good article.

Whether it hindered or helped his writing, the fact is – he wrote. As you once said to a discouraged writer, “If you can stop and want to, then stop…” knowing full well that writers write…they just do and they don’t stop, even when life and its issues get in the way! So, my friend – you are right on once again and your article proves it.

Some writer’s need the experience of life before they begin writing really well. I treasure my “Complete O. Henry” where the editor quotes someone he knew who had KNOWN Henry, and recalled them all eating in a NYC establishment where someone asked Henry where he got the ideas for his stories, and Henry replied that he got them everywhere, there were stories in everything. Henry pointed to the menu and said “There’s a story in this,” and made one up on the spot. Among O. Henry’s themes, were reunited lovers who hold on against all odds. I’m guessing that theme was personal. And that he wrote of what might have been for him…….

Good post. I knew very little of this about the man, though I have read many of his stories. I even remember when The Ransom of Red Chief was an after school movie.