Monday, November 12: The Scribbler

TALESPINNING V. WORDSMITHY

by James Lincoln Warren

Saturday evening, I attended a cocktail party given jointly by the Mystery Writers of America Southern California Chapter and Sisters in Crime Los Angeles Chapter. At one point during the evening, I approached a friend, Thomas B. Sawyer, best known as the showrunner for “Murder, She Wrote” some years ago, who was talking with an attractive and bright young woman. I’m ashamed to admit that I don’t remember her name, but on the other hand, when we were introduced, she asked me, “Are you a writer, too?”

All right, I know my name is not exactly a household word, but you’d think that at a gathering of writers, one would assume …

Anyway, she proudly (and with complete justification) proclaimed that a story she wrote was being published in an upcoming SinC/LA anthology.

“Are you a short story writer, then?” I asked, not to belabor the obvious.

“Sometimes,” she said.

“Then you have a novel in the works.”

“Don’t we all?” she innocently replied.

After that, the conversation veered toward writers who write both short stories and novels. Regarding one famous author, she said, “I don’t care much for his novels, but I love his short stories. He’s a better storyteller than he is a writer.” (Emphasis added.)

Well, I’m not sure that she was right in this particular instance, because I have no idea what she meant by the difference between being a good storyteller and being a good writer. I can only assume she was referring to certain technical issues like well-chosen diction and fluidity of style. “There are some very good writers aren’t very good storytellers, too,” she observed.

I responded by pulling out what for me is something of a chestnut, making the point that if technique is obvious, then it shows poor writing, no matter how advanced or sophisticated the prose, since the reader should be so engaged in the work as to be oblivious to its narrative artifice.

But she had a point.

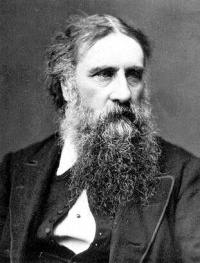

C. S. Lewis, certainly one of the best writers of the last century, adopted for his mentor the nineteenth century fantasist George MacDonald, whose most famous works are Phantastes, Lilith, and The Golden Key. W. H. Auden said of MacDonald that he “is pre-eminently a mythopoeic writer…. In his power … to project his inner life into images, beings, landscapes which are valid for all, he is one of the most remarkable writers of the nineteenth century.”

C. S. Lewis, certainly one of the best writers of the last century, adopted for his mentor the nineteenth century fantasist George MacDonald, whose most famous works are Phantastes, Lilith, and The Golden Key. W. H. Auden said of MacDonald that he “is pre-eminently a mythopoeic writer…. In his power … to project his inner life into images, beings, landscapes which are valid for all, he is one of the most remarkable writers of the nineteenth century.”

But Lewis, despite the fact that he “regarded MacDonald as my master,” has this to say about MacDonald’s skill as a writer:

If we define Literature as an art whose medium is words, then certainly MacDonald has no place in its first rack — perhaps not even in its second. There are indeed passages where the wisdom and (I would dare to call it) the holiness that are in him triumph over and even burn away the baser elements in his style: the expression becomes precise, weighty, economic; acquires a cutting edge. But he does not maintain this level for long. The texture of his writing as a whole is undistinguished, at time fumbling. Bad pulpit traditions cling to it, there is some times a nonconformist verbosity1, sometimes an old Scotch weakness for florid ornament … sometimes an oversweetness…. But this does not quite dispose of him even for the literary critic…. The critical problem with which we are confronted is whether this art — the art of myth-making — is a species of literary art. The objection to so classifying it is that the Myth does not essentially exist in words at all.

Well. What do you say to that? Lewis obviously thought that the stories MacDonald had to tell were much more important than the words he used to tell them.

Nautical slang gave us the metaphor of storytelling as spinning yarn from wool. If you’ve never seen anybody actually use a spinning wheel, this involves taking an inchoate mass of confused fiber and stretching it out into a long, thick thread: yarn. Like the spinner, the storyteller makes of a woolly cloud a cohesive string with beginning, middle, and end. “Yarn” even has a secondary meaning as a story.

Actual writing, contrariwise, is frequently compared smithing: going at it hammer and tongs, beating formless metal into a anything from a horseshoe to gold filigree, tempering and alloying by virtue of indefatigable strength and consummate skill, making something as exquisite and functional as a sword, whether intended for battle or a courtier’s hip.

Janet Hutchings, EQMM’s fabulous editor, once told me that she preferred good storytellers to good writers, but that good writing really helped. Linda Landrigan, AHMM’s equally fabulous editor, once informed me that she likes stories that seem like they’re about one thing, but are actually a vehicles for expressing something deeper than the story itself.

And if we have MacDonald on one end, we have William Shakespeare on the other, the playwright who is generally regarded as the greatest storyteller of all time, but who mined every conceivable source for plot material, and who was not above recasting tales very familiar to his audience because he knew they could follow along. Let’s face it: you don’t read Shakespeare for the stories. You read him for the language.

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury

Signifying nothing.—Macbeth,V,v

When asked my opinion of J. K. Rowling, I once said that I admire her and think she is a marvelous storyteller, but a much less gifted writer than classic authors of English children’s literature such as Kenneth Grahame or A. A. Milne. I love Harry Potter — but I have to admit I don’t love him as much as I do Toad, Rat, and Mole, and Pooh, Piglet, and Owl.

Yes, I think that Lewis is right that there are wonderful stories that are completely independent of how they are expressed. But on the other hand, I think it is a storyteller’s job to elevate his narrative to highest level within his power, to use every technique at his command to make the story and its telling as unforgettable as he can. Would Marlowe have made as great an impact on the crime genre if he hadn’t had that wonderfully wicked gift with wild metaphors? Wouldn’t Peter Wimsey be completely ludicrous if he weren’t so amazingly articulate? And would we really care about the curious incident of the dog in the night if it weren’t for Holmes’ sly joke?

There are other methods of storytelling than writing, after all, and technique must be a slave to the story. But the words matter, a lot — at least to me.

- Lewis is referring to the fact that MacDonald was a failed Presbyterian minister; “nonconformist” alludes to nonconformity to the theology of the Church of England. [↩]

Geo. MacDonald is also notable for being a reader of Lewis Carroll’s “Alice” books. I mean literally! He knew Carroll, took the manuscript home, read it to his family who loved it and insisted that Carroll finish the tale. (P.S., one of C.S. Lewis’ other mentors was E. Nesbit. She’s more fun to read today!)

Robin Cook (the author, not the British polititian… okay, the American author, not the British author), is a genius at plot and adept at melding medical technology and current events.

In the late 70s, I read Robin Cook’s medical thriller, Coma, and enjoyed the movie. Perhaps ten years later, I picked up another Cook novel, and was surprised and dismayed at the level of writing. Thinking it was a fluke, I picked up another of his books and was even further disappointed with the writing. Robin Cook is a great storyteller, but I almost stress out at the writing.

From a reader’s perspective, I prefer a good storyteller. I must add that good writing helps tell the story while making it memorable.

I am an avid reader who is now just beginning to appreciate the conception, labour and birth of a good, well written story. Keep telling your stories and I, along with the rest of the reading world, will continue enjoying them

If Lord Peter weren’t so amazingly articulate, he’d be Bertie Wooster.

Oh, but Bertie is exactly as articulate as he needs to be.

A decade ago when I judged short stories for the Edgars I discovered that all the stories I really liked has at least one of three qualities: a brilliant plot set-up, a brilliant surprise ending, or what I can only call “heightened language,” a use of English so telling you have to admire it (and not so precious that it annoys you).

The first two categories are about storytelling, the last is about writing.

The storytellers I admire are also good writers. I can’t separate the two.

Re Wimsey v. Wooster, I have to say that I regard P. G. Wodehouse as one of the most impeccable, if impeccable is the word I want, stylists of English prose ever, and that any Jeeves opus is a perfect example of a story one cannot imagine being conveyed in any other manner than it is. Or something. Really, I mean to say, what?