Sunday, October 26: The A.D.D. Detective

POE’s ANALYTIC POWERS of DETECTION

by Leigh Lundin

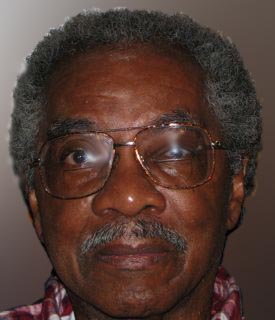

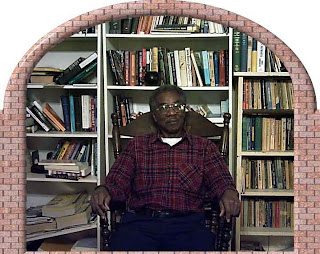

The first amazing thing about Louis Willis is that after retiring from 42 years of government service, he earned his master’s degree in English literature from the University of Tennessee. It’s no surprise his favorite authors include William Shakespeare, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Arthur Conan Doyle, Raymond Chandler, Walter Mosley, Charlotte Carter, William Faulkner, Katherine Ann Porter, and Eudora Welty. While he’s a voracious reader of mystery fiction and operates a blog to educate others about black American writers, he reserves one month each year to reading contemporary non-fiction. Louis says his greatest disappointment is knowing he won’t be able to read all the works he wants to.

Another amazing thing about Mr. Willis is that he’s writing a book, a critical analysis of black mystery writers "before shuffling off to the Great Library" in the Sky.

Louis writes, "Why do I like mysteries? Tell me a story is what I want writers to do. Stories should entertain first, whatever else they may do. When I read a mystery, especially detective stories, I can sit back and let my mind go. I don’t have to struggle with trying to figure out what the author is trying to say about important social issues or our place in the larger scheme of the universe. Mysteries tell stories better than any other genre. No matter if the writer wants to make a political statement or advocate a cause, he or she must stay within the plot structure of the mystery genre or else the story will fail. Borges has said better than I can: ‘… a detective story cannot be understood without a beginning, middle, and end.’"

We couldn’t agree more. Here’s Louis Willis.

The Five Analytic Powers in The Art of Detection

In the prefatory remarks to “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Edgar Allan Poe analyzes the five analytic powers of observation, inference, intuition, imagination, and identity. An abstract argument, of course, is of little use unless it is illustrated through examples. Thus, Poe created Auguste C. Dupin to demonstrate the workings of the analytic powers. In this article I discuss those five analytic powers.

Observation

The detective, writes Poe, makes “in silence, a host of observations and inferences. So, perhaps, do his companions; and the difference in the extent of the information obtained, lies not so much in the validity of the inference as in the quality of the observation.” Observation is thus the first step in the analytic process. During his observations, the detective accumulates the evidence with which he will begin to put together the clues, using the other four steps of the analytic process, to solve the mystery. For Dupin, the greatest fictional detective, “Observation has become…a species of necessity.” He explains to his narrator/companion that in observing the scene, “it should not be so much asked ‘what has occurred,’ as ‘what has occurred that has never occurred before.’”

Like the modern descendent of Dupin and Holmes, Adrian Monk, the eccentric sleuth of the television series “Monk,” the detective must look for the unusual, for “…it is by these deviations from the plane of the ordinary that reason feels its way, if at all, in its search for the true.” (Dupin).

Inference

At this point in the analytic process, memory begins to play a very important part, for as Poe says: “To observe attentively is to remember distinctly.” Reviewing the facts of the case in his memory, the detective next “makes in silence, a host of…inferences.” Thus, the detective’s suspicions are not drawn out of thin air but are educated guesses, which in fact is what inferences are.

In his analysis of the facts, based on his inferences, the detective begins to sort the evidence, using one of the two types of reasoning (he may over the course of the investigation use both): deduction or induction. He may reason a posteriori, deducing from his observations the probable causes of what he has observed. He may use inductive reasoning to arrive at the probable causes. In the first instance, he makes necessary inferences based on deductions. In the second instance, he makes probable inferences based on inductions.

Intuition

The detective’s “results brought about by the very soul and essence of method, have, in truth, the whole air of intuition.” Poe, thus, considers intuition to be a vital part of the analytic process. Intuition is one of the non-rational elements of the process, depending as it does on the unconscious knowledge stored in the detective’s mind, the sources of which are gut feelings, instinct, or hunches, all terms for intuition. The difference between inference and intuition is the former is a guess based on empirical evidence while the latter is instinctive. Intuition is the little voice that whispers in the detective’s ear.

The detective continually draws inferences from his analysis of the evidence. During this process, his intuition adds to his knowledge of the situation and leads him in a direction the reason for which he cannot explain. He must, then, verify his tentative conclusions through the last two powers of the analytic process, imagination and identity.

Imagination

Poe on imagination: “It will be found, in fact that the ingenious are always fanciful, and the truly imaginative never otherwise than analytic”. Imagination is, perhaps, the most versatile of the five analytic powers, for it allows the detective to consider various solutions, although, for a while, it may send him down the wrong path, where, if he works in the mean city streets, he will be hit on the head and knocked out cold. In the English countryside, he will experience a sense of lurking danger but probably no real physical danger.

“Intellect marches, but imagination rambles." (anonymous) The intellect, the systematic organizer of the evidence, cannot begin its march toward the revelation of whodunit, howdunit, and whydunit until the imagination, in its rambling, has at least peeped at the jumble of rational and non-rational thoughts. Nevertheless, intellect wants and tries to move the mind immediately to the analysis, believing it has a solution in sight. However, the imagination is irresistible and relentless, insisting on having its say in arriving at a solution. The imagination suggests different solutions until the intellect sees the correct combination of facts that brings together the evidence to support the conclusion. (Intellect, as I’m using it, is not one of the powers but the brain, the “little grey cells,” that control the powers).

The mind has the ability to consider things that are not immediately present but were present to the senses in the past. This “impression of the senses,” Aristotle explains, “is accordingly the basis of memory. The representative pictures which it provides form the materials of reason.” Imagination depends upon the senses to stimulate the memory, and the memory calls upon what it has previously experienced.

Thus, the detective employees his previous experience through imagination at each step in putting together mental pictures of the situation, only one of which will reveal itself as true. This artist further uses his imagination to arrange the clues into possible patterns of behavior of the murderer (and sometimes the victim) that will eventually lead to the identity of the murderer.

Identification

Poe on identity: “Deprived of ordinary resources, the analyst throws himself into the spirit of the opponent, identifies himself therewith, and not unfrequently sees thus, at a glance, the sole methods (sometimes indeed absurdly simple ones) by which he may seduce into error or hurry into miscalculation.” At this point in the analytic process, the detective becomes a kind of profiler, using his imagination, to get into the suspect’s mind, becoming the suspect and observing, not only the crime scene, but also each individual connected to the crime as the suspect would observe them. The information he has gathered in the observation, inference, and intuition phases now will, along with imagination, aid him in tripping up the suspect because he is able, knowing the way the suspect thinks, to anticipated his next move or may, perhaps, force the suspect into making a fatal move of which he is quite unaware.

Auguste C. Dupin, the archetypal analytical detective, is still the best example of how the analytic abilities, the rational and non-rational, work in the art of detection. He is creative and purposeful. He is an artist who thinks like a scientist because solving crimes is a rational process that requires imaginative thinking. As an artist, he uses his intuition and imagination in his search for the truth. Since truth arrived at through imagination may be false, like the scientist, he uses reason to verify his findings.

However, the detective need not, like Dupin and Holmes, be a “pure thinker” who excludes everything from his mind, refusing to allow outside matters to disturb his thoughts. In fact, such extraordinary concentration might be dangerous, as it proves to be for Jorge Luis Borges’s detective in the short story “Death and the Compass,” in which police detective Lönnrot considers himself “a pure thinker, an Auguste Dupin.” The detective may be a non-pure thinker such as most of the hardboiled sleuths are.

Despite the advances in the forensic sciences, fictional detectives still must, as Poirot would say, use the little gray cells. The art of detection, thus, requires a mind that has the skill to use the rational powers of observation and inference and the non-rational powers of intuition, imagination, and identity in such a way as to arrive at the truth. No matter whether he is an amateur, police, or private, the detective must be an egoist and a little arrogant to be successful. Philosophically, like Poe, the detective must believe that the universe is rational and, therefore, may be understood using the methods of deduction and induction.

Louis Willis, literary analyst, reviews black writers and stories featuring Afro-American characters. Visit Louis Willis’ African-American Crime Mystery Authors blog.

I enjoyed the article. Lots to think about. I wonder if intellect often overrides (or stifles) imagination for some. Sometimes it does in my writing, but never in my reading. Probably doesn’t make sense but oh well.

Thank you for the article, Mr. Willis. Thought provoking.

Hope Mr. Willis doesn’t overlook Percy Spurlark Parker. He’s a good one as well as a fine fellow.

Thanks for reminding me about Percy Spurlock Parker. I had read about him but never got around to reading him. Your note sent me online where I found a copy of “Good Girls Don’t get Murdered” that is within my budget.