Monday, November 10: The Scribbler

WORDIES

by James Lincoln Warren

… dixeris egregie, notum si callida verbum

reddiderit iunctura novum.–Horace… you will express yourself eminently well, if a dexterous combination should give an air of novelty to a wellknown word.

— trans. by Christopher Smart (1722 – 1771)Happy your art, if by a cunning phrase

To a new meaning a known word you raise.— trans. by George Colman the Elder (1732 – 1794)

Horace, of course, was writing about writing poems —the quotation is from Ars Poetica (The Art of Poetry). But that’s only because short stories hadn’t been invented yet. Most advice given about poetry applies equally to any kind of writing, and especially to short fiction, where every word counts. And being Criminal Brief‘s resident Diction Cop, I confess that I have a passion for words in themselves.

Horace, of course, was writing about writing poems —the quotation is from Ars Poetica (The Art of Poetry). But that’s only because short stories hadn’t been invented yet. Most advice given about poetry applies equally to any kind of writing, and especially to short fiction, where every word counts. And being Criminal Brief‘s resident Diction Cop, I confess that I have a passion for words in themselves.

There are lots of ways to teach an old word new tricks. The easiest is turn one kind of word into an other, i.e., verbifying nouns (“parenting skills”), using verbs as nouns (“the reveal”), using adjectives as nouns (“he’s a liberal/conservative”), and so forth—but especially turning nouns into modifiers.

The simplest way of doing this is just to plug the noun into a modifier’s syntactical slot (“his girl Friday”). But over the last couple of decades, wordsmiths on the cutting edge have preferred the long-standing technique of suffixation (or suffixion), i.e., adding an ending to a word that alters its grammatical function. Turning an adjective into an adverb, for example, can be done by appending “-ly” to the end of the adjective: public, publicly; quick, quickly; bad, badly.

Nouns can be turned into adjectives by any number of suffixes, among them “-some” (“burdensome”) and “-ish” (“freakish”), but the runaway favorite among slang-bangers is “-y”, championed by Buffy the Vampire Slayer and her minions, who gave us such useful additions to the lexicon as “cartoony”.

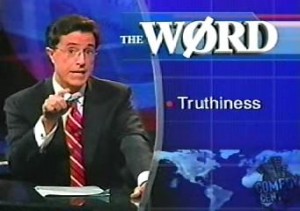

Lately, beginning I believe with political comedian Stephen Colbert, the “-y” suffix has come to mean something that has the appearance of the root word’s meaning without actually being authentic, to wit, truthy and truthiness : “We’re not talking about truth, we’re talking about something that seems like truth—the truth we want to exist.” 1 An example of the expansion of this principle is the oft-heard “mavericky”, used by numerous left-leaning broadcast news commentators in questioning the actual “maverick-itude” of the late Republican presidential candidate and his, um, hockey mom Friday.

Lately, beginning I believe with political comedian Stephen Colbert, the “-y” suffix has come to mean something that has the appearance of the root word’s meaning without actually being authentic, to wit, truthy and truthiness : “We’re not talking about truth, we’re talking about something that seems like truth—the truth we want to exist.” 1 An example of the expansion of this principle is the oft-heard “mavericky”, used by numerous left-leaning broadcast news commentators in questioning the actual “maverick-itude” of the late Republican presidential candidate and his, um, hockey mom Friday.

The “-tude” suffix, which usually forms an abstract noun out of an adjective, was everywhere in evidence this season: “meme-itude”, “lurk-itude”, “suck-itude”, etc. It is distinct from “-age”, which although also abstract, usually refers to some form of collective, i.e., several instances of the root taken together as a whole: “clueage”, “kissage”, “lurkage”.

My wife, using an entirely different application of the “-y” suffix, calls these slangy neologisms “wordies”. Margaret, being of Russian descent, has an frequent tendency to apply diminutives to things, and the head boss chief diminutive in English is “-y” or its variant, “-ie”: Jim, Jimmy; Deborah, Debbie; mate, matey. (Much preferred over about the only other diminutive in English, “-kins”: “Dudderkins” was used with devastating effect by J. K. Rowling when she applied it to an unattractive character.)

“Wordy” as a noun is actually a venerable Scots variant—“She her man like a lammy led Hame, wi’ a well-wail’d wordy” (Allan Ramsay, 1718). We’re all familiar with “wordy” as an adjective, a synonym for “verbose”—Robert Louis Stevenson once described someone for whom he had no respect as “a wordy, prolegomenous babbler.” (Whereas I, Gentle Reader, am a prolegomenous scribbler, of different character entire.)

Just as “truthiness” was in limited use before Colbert put his spin on it—“Everyone who knows her is aware of her truthiness” (J. J. Gurney, 1824)—Margaret’s coinage is a use for our times. It satisfies Horace’s requirement for novel use of a known word.

Now I have a confession. I like wordies. They demonstrate a laudable irreverence and are clearly understood by everyone. This makes them different from most slang—slang is usually a shibboleth, identifying its users as members of a specific group, like surfers or convicts or musicians. As used by Buffy’s Scoobies, wordies, by virtue of their playfulness, only identified their users as being youthful, but cut across all other social barriers.

Now I have a confession. I like wordies. They demonstrate a laudable irreverence and are clearly understood by everyone. This makes them different from most slang—slang is usually a shibboleth, identifying its users as members of a specific group, like surfers or convicts or musicians. As used by Buffy’s Scoobies, wordies, by virtue of their playfulness, only identified their users as being youthful, but cut across all other social barriers.

These days you don’t even have to be young to use them, although if you’re at all jealous of your, ah, dignitude, then wordies should probably be avoided. They don’t belong just anywhere, after all, but they are a golden resource for the inventive story-teller seeking a certain tone.

You might say wordies are all expressiony.

- “The Colbert Report”, October 17, 2005 (premiere episode) [↩]

I remember reading the words “cartoony” and “cartoonish” in the early ’70’s, long before Buffy came along! Another new one has to be uses of the word “friend,” as in “to friend” or “friended,” as on Facebook. Me, I babble. Thanks and “good words to you!”