Monday, November 24: The Scribbler

SERIES-OUS BUSINESS

by James Lincoln Warren

A common feature of genre fiction is the series protagonist. There are rare examples in mainstream literature—John Updike’s Rabbit books and John Galsworthy’s Forsyte Saga come to mind, and there’s also Anthony Trollope—but generally speaking, the series character is confined to science fiction, crime, adventure, suspense, horror, and fantasy.

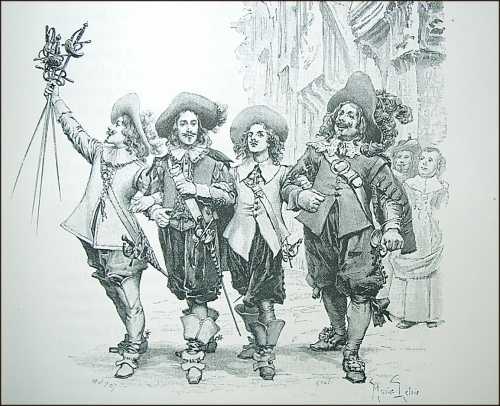

The most famous series character of all time is, of course, Sherlock Holmes. But he wasn’t the first. I am by no means certain of this, but the earliest series in fiction that I am aware of, by which I mean a sequence of more than two stories following the progress of a fixed cast of characters, is the d’Artagnan Romances of Alexandre Dumas, père. You could, I suppose, call it a just a trilogy—but I think of a trilogy as planned, like a triptych. Dumas wrote sequels based on the success of each book, and that, to me, makes it a series. Papa D knew a good thing when he sold it.

Short stories are as rich with series characters as novels, witnesseth whereof Holmes himself, who appeared in sixty-six short stories but in only four novels. A six-volume study of series characters in early pulp fiction, Yesterday’s Faces, was written by Robert Sampson, winner of the 1987 Edgar for Best Short Story (“Rain in Pinton County” in the late lamented The New Black Mask).

I think that series characters are the literary descendants of culture heroes like Hercules and Robin Hood, who themselves figure prominently in series of linked stories and are frequently identified with psychological archetypes. (Please stop me before I spin off into opaque discursive glossolalia again!)

Like Melodie and Rob, I write mostly about series characters, and when I invented Treviscoe and Cal Ops, I intended them to be series. (I also intended Mrs. Stavacre, the parish Searcher in “Mother Brimstone”, to be a series character, but she hasn’t returned yet. She’s having trouble finding the right plot, she says.) At the time, it never occurred to me why I wanted to write a series. Maybe it was because I wanted to emulate Raymond Chandler and Patrick O’Brian. Maybe I had delusions of a Treviscoe franchise to rival James Bond.

But there are three main reasons for writing about a series character:

(1) The fact that a story is part of a series helps establish readers’ expectations. You know more or less what the flavor of a story is going to be if Meyer and McGee are sitting on the deck of the Busted Flush, discussing how times are changing for the worse and drinking icy cold Boodles gin. Trav will rescue a wounded bird, fall in love and have his heart broken, and go toe-to-toe with a violent and cunning sociopath who will meet a poetically just demise at McGee’s hands while putting him in the hospital with grievous wounds. When McGee is discharged, he and Meyer will drink icy cold Boodles on the deck of the Busted Flush and discuss how times are changing for the worse.

(2) Multiple stories may assist in developing the hero’s character more fully. Sherlock Holmes may never change, true, but many series characters change a lot during their careers. Horatio Hornblower is a prime example. In crime fiction, the Harry Bosch at the end of The Last Coyote is a very different Harry from the one at the end of The Black Echo. Lately, Harry has been almost mellow compared to the moods he endured in his earlier career, but the old anger and impatience with procedure certainly came out in The Overlook. But even then, Harry knew exactly how to play it without landing in serious trouble, displaying a prudence he would have completely ignored in the past.

(3) The readers refuse to let the character go. This happened with both Sherlock Holmes and James Bond. The drop off the cliff at the Reichenbach Falls and Rosa Klebb’s poisoned shoe-dagger were both intended to be fatal. But the fans decreed otherwise.

And those are also the reasons I read series fiction. My favorites? Gosh. Where to start? In no particular order: Sherlock Holmes, Philip Marlowe, Horatio Hornblower, Miss Marple, Tarzan, Fafhrd & the Gray Mouser, James Bond (Ian Fleming’s, that is, not Cubby Broccoli’s and Harry Salzman’s), John Aubrey & Stephen Maturin, Harry Flashman, Corwin of Amber, and Travis McGee. I’m sure I’ve left some very important ones out and trust the Gentle Reader to fill in the more egregious lacunae.

As my own series are not widely known, I sadly confess that I am not motivated to write more concerning them by Reason Number Three. The first two, however, are near to my heart. I try to show a different aspect of Treviscoe’s personality in each story he’s featured in, bearing in mind that in a short story, only the characterization which is essential to the story should be included. The same applies to Carmine Ferrari, the narrator of the Cal Ops stories. This means that the crimes must be sufficiently variegated to call forth different thoughts and reactions from the protagonists. It also makes them more fun to write, and hopefully, more fun to read.

My characters and I stick together. I like them and I like writing about them. And that’s the best reason of all for writing a series.

I guess it’s one for all and all for one.

A series character is like an old friend. It’s good for the reader, and it’s good for the author.

The only disadvantage I can see to series characters is that sometimes a plot or a theme doesn’t work with your series. For instance, when Westlake was trying to write a Parker novel, and found that the caper wasn’t working. The emerald Parker and his gang stole wouldn’t stay stolen. The book just didn’t have the right tone for a Parker novel. Thus was born Westlake’s “Dortmunder” series.

Tom Sawyer was a series character. He and Huck appeared in a total of four novels by Mark Twain, and there were three other novels partially written at the time of Twain’s death.

Before Pulps came along, series characters were really big in Dime novels. Characters like Nick Carter, The Old Sleuth, Cap Collier, and Old King Brady each appeared in hundreds of novels in the late 1800s.

And lest we forget, the greatest Pulp fiction series character of them all was Lamont Cranston, who (as The Shadow) could root out the weed of crime with his ability to bend men’s minds.

Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?

The Steinbock knows.

HA HA HA HA HA HA . . . !

A toast (with a fine old wine) to another of Doyle’s great series characters, Doctor J. Watson! Time is sometimes not a friend to series characters who last a long time but it worked in the favor of Ed Hoch’s Simon Ark who is still seemingly “in his seventies” fifty years after his debut story, while the unnamed narrator and his wife age…

Ah, Another toast (same vintage) to you, James, for a fine read today!!

I have a theory about Watson … which will eventually be made known to the world, but it involves the Great Game.

Thanks for your toast, Jeff.

I may be in the minority of Ed Hoch fans, but Simon Ark is my favorite of his series characters. (Nick Velvet is a close second).

Hmmm, Jeff, (referring to one of your comments on yesterday’s A.D.D. column) do you think Simon Ark might be a Time Lord? That could explain a lot!

(For folks wondering what Jeff Baker and I have been going on about, you obviously haven’t watched enough “Doctor Who”).

Limerick For Steve Steinbock:

Simon Ark solves the crimes from the Bad File

Simon Ark fights the Dark with a rad style

Here and now, far away

Long ago, here to day

Wanna bet that he met Brother Cadfael?