Saturday, December 13: Mississippi Mud

FOR WHAT IT’S WORTH

by John M. Floyd

I once read something in a book whose title I don’t remember, written by someone whose name I don’t remember, that put forth the theory that if fiction writers happened to disappear tomorrow from the face of the earth, they — unlike carpenters and mechanics and brickmasons — would not be sorely missed. Life could go on quite well without them or their input. (This was said in a nice way, but that was the gist of it.)

That got me to thinking. For one thing, it’s hard to disagree with that logic. Writers and sculptors and painters and actors and musicians, etc., don’t exactly provide services that are vital to our existence. But you know what? I’m not sure I’d be too fond of a world that didn’t have those people in it.

Which brings up the question: Just how valuable is the service we provide, as writers? For that matter, how does it compare to the talents of other creative or performing artists? Here’s an example using some folks from my home state: Do I feel that the talents of people like Morgan Freeman and Jimmy Buffett and Elvis Presley and Oprah Winfrey are, or were, greater than those of John Grisham or William Faulkner or Eudora Welty or Tennessee Williams? No, I don’t. We’re obviously talking about different kinds of talent. Unless you’re blind and have no taste buds left, you shouldn’t compare apples to oranges.

Having said that, let me pose another question: How much is writing talent worth? We’ve all heard how hard it is to make a living from nothing but writing — and most of the people who do so are either nonfiction authors or New York Times bestsellers, or both. (I always wonder if some of the folks you see shivering in the unemployment lines are short-fiction writers and poets.)

Let me address that question this way.

One day several years ago I was standing around outside my office building with half a dozen co-workers. Some of them were on a smoke break, some were there to enjoy the unseasonably warm weather, and others, like me, were just tired of sitting at their desks. As we stood there talking politics and sports and sharing our opinions of whether it would rain that afternoon, another colleague — his name was Gerald — wandered up holding a cardboard box.

When he was sure he had everyone’s attention, he opened the box, said, “Take a look at this,” and with a flourish pulled out — a duck.

When he was sure he had everyone’s attention, he opened the box, said, “Take a look at this,” and with a flourish pulled out — a duck.

A carved duck. It was a great piece of work, too, more than a foot long and cut from a single block of wood and handpainted down to every single feather. It looked so real I expected it to quack and waddle off down the sidewalk.

“That’s a beauty,” I said to him, and meant it. I was impressed. I couldn’t have created something like that in a million years.

Gerald, I should mention, is a sincerely nice guy, and at that moment he was beaming with well-deserved pride. He told us it had taken him two hours every night for six months to complete the woodworking and the painting, and said he’d already sold the piece. Even more proudly, he told us how much the buyer had paid him for it.

More congratulations, all around. While everyone was still slapping him on the back, another co-worker named Mike stepped out of the building. When he reached the rest of us, he looked up from the magazine he was reading, spotted me, and said to the others, “Look, folks — Floyd’s got a new story in Woman’s World.”

One of the guys smirked and said to him, “I like Good Housekeeping, myself. You got one of those too?”

“Very funny. This belongs to the receptionist. But look here.” Mike turned the magazine so everybody could see my story. It was so short the whole thing was contained on one page. “See the byline?”

Now I was the one getting congratulated and patted on the back. “By the way,” someone else said to me, “what do they pay you for those stories?”

I was of course flattered that anyone even knew about it, but I was also a little embarrassed. Since Gerald the Duck Man was still standing there, I just shrugged and said, “Well, they pay pretty well.” And this particular story was a romance, so its payment was twice that of my usual WW mystery stories.

“How much?” Mike asked me.

“Well, quite a bit,” I said. “Hey, did you see Gerald’s duck?”

“Come on — how much, exactly, did they pay you for this?”

So I told them. And the figure, while not exorbitant, was four times what Gerald had said he had charged for his six-month work of art. After a long silence Gerald, still holding his duck and looking a little stunned, said, “Damn, John. That can’t be worth that much.”

I thought about that for a minute. I started to say something like what I mentioned a minute ago, about different kinds of art and different kinds of talent. Instead, though, I just said to him, “Actually, something’s worth whatever somebody’ll pay you for it.”

I don’t know if I came up with that or if I’d heard it someplace, but I think it’s usually true — at least for material things. If you don’t believe it, talk to those who create and deal in abstract art. Different things appeal to different folks, and to different markets.

Another fact about writing, and specifically short pieces: They have an advantage over certain other items like paintings and sculptures and even handmade furniture. When you sell one of your stories, you don’t lose it. If you’ve retained reprint rights it’s still yours, and you can publish it over and over again.

So, what is your writing worth? Well, mine’s worth a lot to me, and if it sells, it must be worth at least something to others as well.

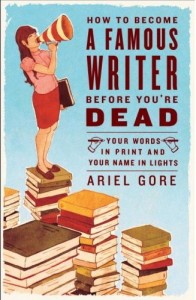

Ariel Gore says, in her book How to Become a Famous Writer Before You’re Dead, that authors should always be proud of their accomplishments. When you give someone a piece of writing, she points out, you’re “providing him with something that has the power to sustain him. You could just as easily be making him a sandwich.”

Ariel Gore says, in her book How to Become a Famous Writer Before You’re Dead, that authors should always be proud of their accomplishments. When you give someone a piece of writing, she points out, you’re “providing him with something that has the power to sustain him. You could just as easily be making him a sandwich.”

I like that analogy. And it’s even better than that, in a way: With a story, you don’t run the risk of making him sick.

Well … hopefully.

Hope you are right about not making the reader sick, John. Funny how things affect people, though. I’m still feeling a little sad about Gerald standing there with his duck. Sounds like you felt the same way.

I feel for poor Gerald but market forces always rule.

if writers and artists disappeared tomorrow, we’d simply reinvent because someone has to explain the unexplainable.

If we’re going to be truthful here, I must admit that that piece of art and woodworking required more talent than I’ll ever have. I suppose I’m just fortunate that there’s more than one way to demonstrate creativity.

But that little scene always comes to mind anytime someone implies that writing isn’t as “worthwhile” as other jobs and hobbies.