Sunday, January 4: The A.D.D. Detective

CHARACTER and PLOT

by Leigh Lundin

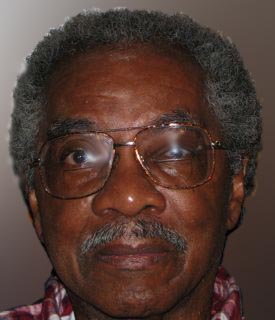

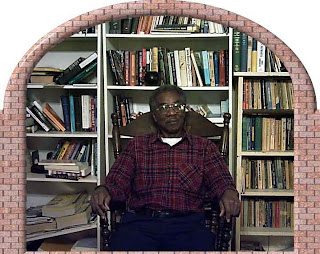

For the first Sunday column of the new year, we turn to our erudite friend, Louis Willis, who took time before the holidays to write for us. Louis is a scholar, writer, and critic with a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.  You may remember his favorite authors include William Shakespeare, Langston Hughes, Arthur Conan Doyle, Raymond Chandler, Walter Mosley, Charlotte Carter, William Faulkner, Katherine Ann Porter, Eudora Welty, and Zora Neale Hurston, whose home is minutes from my house.

You may remember his favorite authors include William Shakespeare, Langston Hughes, Arthur Conan Doyle, Raymond Chandler, Walter Mosley, Charlotte Carter, William Faulkner, Katherine Ann Porter, Eudora Welty, and Zora Neale Hurston, whose home is minutes from my house.

He reserves one month each year for reading contemporary non-fiction. Louis says his greatest disappointment is knowing he won’t be able to read all the works he wants to. Louis is presently reading Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, which may have prompted today’s article as it has more than 400 characters and a notoriously convoluted plot.

A connoisseur and student of mystery fiction, Louis is writing a book, a critical analysis of black mystery writers. In furtherance of that goal, Louis operates a blog to educate others about black American writers. Check it out.

Thoughts on Character and Plot

Literary fiction versus genre fiction — character driven versus plot driven.

Literary fiction, ignoring the fact that "character driven" and "plot driven" are merely descriptive terms, is often privileged over genre fiction because the former is "character driven." Critics, reviewers, and writers who seem to disparage "plot driven" or genre stories, ignore the fact that character and plot are of equal importance.

Thus, character is important in any type of fiction but needs something to do, for without action character is impotent. As Milan Kundera notes in The Art of the Novel, "action is … seen as the self-portrait of the one who acts." Action or plot reveals character. Plot is the linchpin that connects the other elements and provides the logic for the actions of the characters. Plot development is a dynamic process that gives the reader a sense of movement toward something inevitable, of an unfolding of events that will profoundly affect the characters. It is the guide that directs the reader’s attention.

I have said that character and plot are of equal importance. In some stories, however, one or the other may predominate. In most genre stories, such as mystery, adventure, and romance stories, the emphasis is on what happens and not so much to whom it happens. Nevertheless, in these plot driven-stories, the hero must be a character whom the reader admires and can sympathize with. The villain, on the other hand, while he or she may have some good qualities, must be a character who, when she or he loses, the reader sheds no tears.

In literary fiction (a term I hate because I’m not sure what it means), plot development is likely to be subordinate to character development. Unlike in genre stories, characters in literary stories are more likely to resemble real people because of their responses to the situations in which they find themselves reflects change in personality or philosophy. In other words, genre stories depend on the development of plot. Literary stories depend on the development of character. In either case, character cannot do without plot and vice versa. In the ideal story, neither plot nor character predominates.

Readers read fiction primarily for entertainment. They enter what one writer/critic has called the "compensatory realm" to get away for a few hours from the stress of their daily problems.

While writing this article, I convinced myself that I should reread two of the great crime stories— Macbeth and Crime and Punishment— to reacquaint myself with the connection between character and plot. Maybe the two literary masterpieces will help me distinguish the difference between literary and genre fiction.

Louis Willis, literary analyst, reviews black writers and stories featuring Afro-American characters. Visit Louis Willis’ African-American Crime Mystery Authors blog.

Pynchon and ADD don’t go together unless it’s to teach beginning writers what not to create (if you wish to be read) in character and plot.

There’s a story that the Pulitzer core committee unanimously recommended Gravity’s Rainbow and the Pulitzer voting body unanimously rejected it. Probably both were right.

My hat off to Louis, both stalwart reader and a good writer. The compare and contrast makes a good, seldom seen point.