Friday, March 13: Bandersnatches

NINETY-SIX BRIEFS

by Steve Steinbock

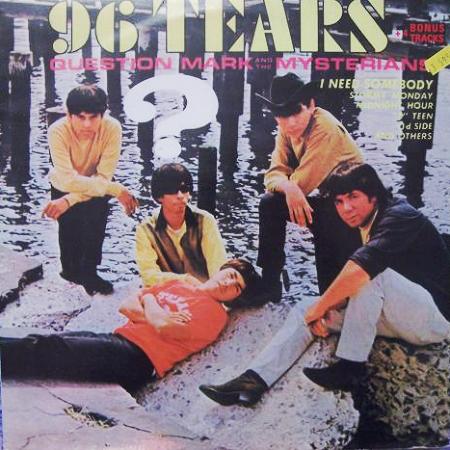

In the early sixties, a young man named Rudy Martinez took on the moniker “Question Mark” and became the frontman for the Michigan rock band “Question Mark and the Mysterians.” Their name alone may warrant acknowledgement in the world of mystery. But I invoke them today, in this Bandersnatches column of tangents, digressions, and non-sequiturs, solely because this is my ninety-sixth column at Criminal Brief, and Question Mark’s biggest hit was the song “96 Tears.”

That doesn’t imply that my columns resulted in tears, either on my part for writing them or, God forbid, on your part for reading them. Although I wonder if my chronically tardy submissions have caused more than a few tears on the part of Criminal Brief commander and editor-in-chief James Lincoln Warren. If such is the case, sorry, Jim.

For the Love of Words

I’ve been listening to a lecture series by Wheaton College professor of medieval literature Michael D.C. Drout. I’ve listened to several of his lecture series, and have enjoyed his irreverent approach to grammar, linguistics, and the history of English. Many of the observations that I share in this column were triggered, if not stolen outright, from Professor Drout. Thievery is the sincerest form of flattery.

The Devil and Noah Webster

To my knowledge, Noah Webster was completely unrelated to Daniel Webster. They both lived around the same time. In fact, their paths may have crossed somewhere in New England in the early part of the nineteenth century. That might make an interesting story.

Daniel Webster did appear as a character in a famous short story by Stephen Vincent Benét. If I really wanted to digress, I could tell you about Benét, and how he borrowed a theme from Washington Irving, and then I could spend pages lauding the virtues of Irving as a great American short story writer. But as Melodie was wont to say earlier this week, I digress.

Daniel Webster, incidentally, being a great statesman and attorney, probably filed far more than ninety-six briefs. And in British slang, he might be referred to as a “brief.”

Noah Webster, on the other hand, was a lexicographer and authored several dictionaries including An American Dictionary of the English Language, which evolved into the modern Merriam-Webster Dictionary. (I wonder what Webster would have thought of my use of “authored” as a verb).

Webster was responsible for many of the spelling reforms that distinguish American English from proper English. He changed the ou in words like colour and honour into the simple o. He swapped the r and e in centre so it became center. He changed defence to defense and changed traveller to traveler. Our word tongue was almost changed to tung. But ultimately caution (and a wagging tongue) won out.

When I look at the changes Webster made in American spelling, I have to wonder. If he was going to bother making any changes at all, why didn’t he go further? I mean, if you’re going to do something, go all the way. It would be like going partially metric. Come on, Noah. Fish or cut bait.

Since the invention of movable type, spelling reform hasn’t gone over very well. But it’s been a long and hearty debate. George Bernard Shaw, who invented his own phonetic alphabet and campaigned for a major spelling overhaul, once pointed out that “Our present spelling is incapable of indicating the sounds of our words and does not pretend to.” It was also Shaw who was, I believe, the first to point out that the letters GHOTI could be pronounced “fish.”

But spelling isn’t static. The sort of silly abbreviations that we see in kid’s text messaging (phrases like CUL8er for “see you later”) gripe me to no end. (I saw an article titled Texting can b gd 4 ur kids). But oddly and ironically, as Michael Drout points out, the spelling form “luv” may actually be more historically valid than the current “love.” In Old English the noun was lufu and the verb was lufian. The change from luf to love came about in order to minimize the use of the confusing letter “U.” About a thousand years ago, when Old English was starting to give way to Middle English, there was a stylized form of writing commonly used by English (and other Germanic language) speakers. Many of the letters were composed of thick vertical lines linked with tiny horizontal lines. Imagine the word MINIMUM written as IIIIIIIIIIIIIII (fifteen vertical lines) with eight thin lines linking some of the thick lines either at the top or bottom. Imagine having to read a whole bunch of that. At was much simpler to change muney, huney, cume, cuver, and luv to the forms we’re accustomed to.

Typographic Violence

The digraph “TH” has led to a lot of confusion in English spelling and pronouncing, not to mention being really difficult for speakers of other languages trying to learn English. Without going into too much history of oral anatomy, a final “TH” sound was at one time indistinguishable from a final “S” sound in certain words. Thus (and the irony of the word “thus” hasn’t escaped me even though it was unintended), when a word in the King James Bible tells us about animals that “creepeth” upon the earth, or when Abraham is told to live wherever he “pleaseth,” or when the Philistine king says “he that toucheth this man,” speakers at the time it was written would have likely pronounced these words as “creeps,” “pleases,” and “touches.”

When I was growing up in Seattle, there was a cool store on the waterfront that was a favorite field trip destination. The store was called Ye Olde Curiosity Shop, and it had a mummy, real shrunken heads, and other things that fifth grade boys relish. The word “ye,” however, is an odd duck. Normally, ye is a second-person plural pronoun, sort of like the modern “you all” or “y’all.” As a definite article, the word the was originally spelled þe (with the now obsolete runic letter “thorn”). When the þ was unavailable, printers would substitute a y. Thus, the became ye – sort of.

Enough of the digressions for this week. Next time around I may be bringing Stephen Vincent Benét, Washington Irving, Jacob Grimm, and/or Dear Frannie to the Bandersnatch table.

Happy Ninety-Six!

I was fascinated to learn something that failed to come up in literature classes, that th was originally pronounced as S.

Sometimes the British spellings make more sense, particularly when it comes to sorting out homonyms such as kerb and tyre. To this day, a single L in words like traveler haunt me and the word editing with one T never looks right.

When it comes to shorthand, I remember complaints about the use of Xmas, although I later read a scholarly argument that Xmas was closer to the original.

I agree that Germanic (and old English) type faces are awful to read in bulk. Books of that stuff could make you go blind! The first time I saw Disneyland spelled in Germanic script, I made a mental text message, WTF?

Leigh, my explanation of the “eth” ending was simplistic. The reality isn’t so cut and dry.

But if we don’t pronounce the “L” in “could” or “walk” or the “C” in “science” or “fascination” (or the “GH” in Leigh!) it strikes me as an unnecessary archaism to pronounce the “eth” ending. But it’s a convention. And those are hard habits to break.

Nevermind Cathtilian Thpanish.