Monday, March 31: The Scribbler

GRAND ALLUSION

by James Lincoln Warren

Story tellers use all kinds of techniques to achieve economy in story telling, and one of the most advanced is the gentle art of allusion or reference. To the literate reader, a skilled allusion imparts a tremendous amount of information without having to strike the nail on the head. Here’s a classic example:

A boy infant is whisked away by the world’s most powerful wizard to be reared by a foster family. All the time he is growing up, he suffers under the tyranny of his foster brother. He is raised in complete ignorance of the magnitude of his own destiny, for he has been prophesied to be the greatest champion the world has ever seen, and when at length that destiny is revealed, it comes as a shattering surprise, redefining the child’s very conception of the world.

This should seem familiar to most readers: it’s the beginning of the story of King Arthur—and also of Harry Potter. By making Harry’s childhood more or less equivalent to King Arthur’s, J. K. Rowling was announcing the heroic and epic nature of her protagonist and his tale. With a childhood like the one he had, Harry has no choice but to grow up into a champion of righteousness.

Allusion only works, however, if the reader is familiar with what is being alluded to. I ran into this problem some time back when I wrote a story called “Mother Brimstone” (AHMM, Jan/Feb 2007). The heroine of the story is a middle-aged widow named Mrs. Emma Stavacre. Mrs. Stavacre does not suffer fools gladly, and in fact, has something of a quick temper. To illustrate this, I had Mrs. S very patiently endure the vain prattling of her daughter up to a certain point, at which point Mrs. S erupts. Originally, I wrote something along the lines of, “At that moment, Mrs. Staveacre’s temper revealed itself as Jupiter unto Semele.”

I was very pleased with this image. However, when Margaret read the MS., her reaction was, “What the hell does this mean? Quit showing off.” (Every self-congratulatory masculine fool should have a wife to keep his ego in check.)

In Graeco-Roman mythology, Semele is the mother of Bacchus/Dionysus, and one of the mortal paramours of the philandering Jupiter/Zeus. Plotting revenge against her erring husband, Juno/Hera disguises herself as an old crone and goes to visit Semele, who is in the family way. When Semele tells her visitor that the father is no less than King of the Gods, Juno plants a seed of doubt in her mind, and suggests that Semele get her husband to promise her anything after swearing on the River Styx, the most solemn oath possible. After tricking him into making this vow, Semele is to demand he reveal himself in his divine aspect. Semele accordingly executes the plan, whereupon Jupiter desperately tries to dissuade her, to no effect. He gathers his smallest rainclouds and wields his tiniest thunderbolt and appears before her, but mortal eyes were never intended to view such splendor and Semele is blasted to dust. (The fœtus survives, of course—otherwise we’d have no God of Wine—sewn into Jupiter’s calf, but that’s another story.)

This was the image I was so pleased with myself for coming up with. Unfortunately for my vanity, most folks have no clue to the story of Semele and Jupiter, and by forcing a meaningless allusion down my readers’ throats, I was indulging in the most egregious conduct an author can commit: I was not giving the audience the respect due them. I was, in effect, saying, “If they have no bread, then let them eat literary cake.” Margaret was completely correct in strongly objecting to this empty display of erudition.

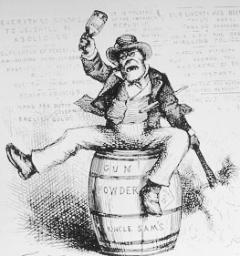

So I changed the passage to, “At that moment, the sputtering slow-match of Mrs. Stavacre’s temper at last breached its keg, with dazzling results.”

So I changed the passage to, “At that moment, the sputtering slow-match of Mrs. Stavacre’s temper at last breached its keg, with dazzling results.”

The question this raises is, how do you know when allusion works or if it flies over everybody’s heads instead? If done properly, of course, getting the allusion is not required for the story to be appreciated. I’ll bet very few readers, especially kids, made the connection between Harry and Arthur, for example. Harry Potter’s story does not depend on the allusion for its success. In this regard, allusion is rather like the element of surprise in battle—it’s great to have it, but if you depend on it and it evaporates, you’re in the hurt locker. That’s what I did with Semele.

But what about other allusions? Some you can pretty well count on as being universal. The Temptation in Eden. The Flood. David and Goliath. Æsop’s Fables. Christ imagery (or its pagan analogs, like Balder or Persephone, which are also stories of sacrificial death and resurrection). Robin Hood. Cinderella. The magical power of Love’s First Kiss. Hamlet. Scrooge. Walter Mitty. And so forth. Others, like Semele or certain sly references to T. S. Eliot, are a little too highbrow most of the time. (Raymond Chandler, of course, made excellent use of Prufrock in The Long Goodbye, but he also had the good sense to inform the reader that he was quoting Eliot.)

We hear all the time that there are only so many stories, and that every thing new is a rehashing of tales that have been told since the dawn of time. Robert Graves went all the way and said there was only one story. I have never subscribed to that theory, but good allusions do assist in putting the action into context and can help provide a sense of relevance to the reader.

And recognizing one can be a kick.

I’m afraid Ceres (or Demeter) soweth upon infertile soil. James, I’d hazard half of those allusions would be lost on the majority of people today.

I believe a few major Biblical stories are still safe, but if it hasn’t been done by Disney or appeared in a pop video, it ain’t happening.

It took the movie The 300, itself from a graphic novel, to shed a little light upon the ancient Persians and Greeks, even though much of the story and the social mores of the time were wrong. Thus history suffers, even as allusion suffers.

I loved Mythology when I was growing up, and I caught the notion that Dumbledore is the “Merlin Figure” in the Potter books, but alluding Potter to Young Arthur just went right over my head!

“But what about other allusions? Some you can

pretty well count on as being universal.”

Speaking as an ex-teacher, don’t bet on it.

Leigh may also be too optimistic:

“I believe a few major Biblical stories are still safe …”

Of course, I taught middle school; maybe the kids pick

this information up in the higher grades–although a

few graduates whom I formerly taught betrayed no such

knowledge in casual conversation.

–Mike