Saturday, June 23: Mystery Masterclass

If you’ve read an issue of Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine in the last twenty years, you’ve almost certainly read a story by the amazing and prolific Jas. R. Petrin. (I knew we were spiritual brothers the first time I saw his byline–I had seriously considered using “Jas. L. Warren”, which is how I sign everything, as a byline myself, but settled on the current mouth-filling conglomeration of syllables instead solely to avoid being identified with the monster magazine publisher, Jim Warren, infamous for being sued into the ground by Harlan Ellison.–JLW) Here, my favorite writer from the wilds of Nova Scotia discusses script writing–but his is a cautionary essay for all writers.

TV WRITERS COULD USE A HISTORY LESSON

by Jas. R. Petrin

Is anyone else getting more and more irked at the trend in TV program production for annoying and unnecessary sound effects? It’s like listening to that old Victor Borge skit on audible punctuation, and he was a comedian. Even the mighty CNN has given in to this cheesy device.

Imagine the chat on the Situation Room director’s headset.

Reverberant voice: “The guy on the traps is demanding a break. He says he’s been drumming for a good seven hours.”

Director: “I’ll tell him when he gets a break. And give that SFX clown a slap. After the kapow! I want more of a bloomp! And right there when we switch out to Nancy on the Beirut feed all I’m hearing is a blap! I want a sha-whump, understand? Like she got hit with an arrow.”

Reverberant voice (petulant): “You said you wanted a swuk.”

Director: “On the switch to the Google Earth view I want a swuk. On Nancy I want a sha-whump, get it? And that damn drummer better stop fading on me. Tell him to put his wrists into it!”

Not only on CNN are we subjected to this but also on drama programming such as C.S.I. The psychology seems to be that the public is essentially brain-dead, and you need fireworks to capture their attention. But wait. Haven’t we tried this before?

Yes we have.

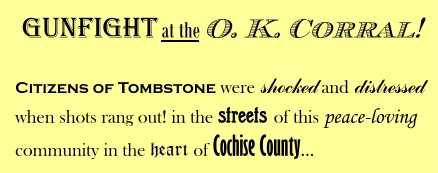

The print media has been there and done that. It’s progressed a hundred years beyond this. Literally. In the late 1800s printers pulled out all the stops (think how that would murder a Bach organ piece). Poster makers employed every print size, ink color and glyph in their type tray to reach out of the pasteboard and waylay a comatose pedestrian. Newsroom typesetters feverishly displayed every font they could lay their inky fingers on.

This is the equivalent of banging a snare drum. It was an experiment that failed, but writers learned something from it. Watch the italics. Ease up on the adjectives. Ration the superlatives or you’ll dull their effect. Don’t tug at your reader’s shirtsleeve. Don’t plead for attention. And don’t ladle on exclamation marks for emphasis, even if you have bushels of extra ones cluttering up your desk!!!

Have you forgotten history, all you TV writers out there? Gimmicks are gimmicks, and they make you look silly.

Pow!

“Watch the italics.”

As a reader, I look to italics in dialogue to resolve possible ambiguities in what a character is saying. Take this snippet from William S. Gilbert’s Patience, Act I:

“PATIENCE. Pray don’t misconstrue what I say –/Remember, pray — remember, pray,/ He was a littleboy!

“ANGELA. No doubt! Yet, spite of all your pains,/ The interesting fact remains –/ He was a little boy!”

When the writer of dialogue shows, rather than tells, italics capture those subtle shifts in speech rhythm which make all the difference in the speaker’s/singer’s meaning.

Italics are not always an insult to the reader’s intelligence. Sometimes, they’re crucial to the reader’s understanding.

(scratching head) I’m wracking my brain trying to think of the popular white-suited author who peppered his writing with multiple exclamation points and other gimmicks.

In 1984, when desktop publishing first introduced true typography to the masses, the first thing many people did was to publish newsletters using every face and font in the machine’s repertoire. It took a while to learn what the professionals already knew.