Saturday, April 12: Mississippi Mud

CHARACTER STUDY

by John M. Floyd

I love to read books about the craft of writing. Some are worthwhile and some are worthless, but now and then you find a piece of advice that makes a lot of sense. For example, this point made by Stephen King, in his book On Writing: “I can’t remember many cases where I felt I had to describe what the people in a story of mine looked like,” he says. “I’d rather the reader supply the faces, the builds, and the clothing as well.”

I love to read books about the craft of writing. Some are worthwhile and some are worthless, but now and then you find a piece of advice that makes a lot of sense. For example, this point made by Stephen King, in his book On Writing: “I can’t remember many cases where I felt I had to describe what the people in a story of mine looked like,” he says. “I’d rather the reader supply the faces, the builds, and the clothing as well.”

Do you agree? How much character description do you feel we, as writers, should provide in our stories? How much do we, as readers, really want?

I think King’s right. Personally, to enjoy a story, I don’t require a lot of information about a character’s height, weight, age, race, dress, eye color, hair color, etc. One of my current favorites is John Corey, Nelson DeMille’s wisecracking New York cop, and I don’t think we readers have ever been told anything about Corey’s physical appearance. And you know what? It doesn’t matter. At least it hasn’t mattered to me. I have a mental picture of him, and that suits me just fine.

Which brings up another question: Do you, when you read a story, always put a face with the person you’re reading about? I suppose I do, but I’m not sure everyone does. And I’ve found that I’m not really influenced much by TV or movie depictions of a particular character. To me, Robert B. Parker’s fictional Spenser never looked like Robert Urich, who used to play him in the TV series — in fact the Spenser I see in my mind when I read about him probably looks more like Parker himself, in his bookjacket photos. And one of his other series characters, Massachusetts policeman Jesse Stone, always seems more of a short, lean, Roy Scheider-looking guy to me, than his Tom Selleck version on TV. Go figure.

I am not, however, always so immune to screen portrayals of heroes. If I were to read a novel tie-in to one of the Indiana Jones movies, let’s say (although I can’t imagine doing such a thing), I would have a hard time picturing anyone besides Harrison Ford as Indy, and I always saw Sean Connery as James Bond when I re-read the Fleming novels a few years ago. (By the way, I consider the casting of Roger Moore as 007 to be one of the most lamebrained decisions in film history. Another mistake, in my opinion, was choosing Eriq La Salle to play Minneapolis cop Lucas Davenport in the adaptation of John Sandford’s Mind Prey in 1999. Did any of you see that one? La Salle’s a fine actor — he was outstanding in “ER” — but he just didn’t seem right as Davenport.)

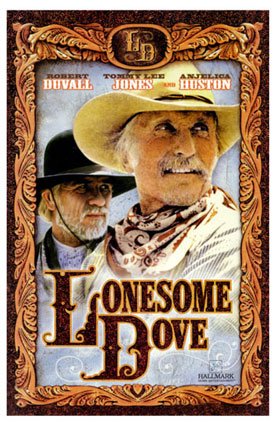

Another example is Lonesome Dove. When I read Larry McMurtry’s novel after seeing the miniseries, I of course visualized Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones as retired Texas rangers Gus McCrea and Woodrow Call through- out the book — but let’s face it, they were perfect for those roles. When I later learned that McMurtry had originally written those characters long ago with Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne in mind, I was amazed. (Then again, Frank Sinatra was the first choice for Dirty Harry Callahan — how strange would that have been?)

Another example is Lonesome Dove. When I read Larry McMurtry’s novel after seeing the miniseries, I of course visualized Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones as retired Texas rangers Gus McCrea and Woodrow Call through- out the book — but let’s face it, they were perfect for those roles. When I later learned that McMurtry had originally written those characters long ago with Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne in mind, I was amazed. (Then again, Frank Sinatra was the first choice for Dirty Harry Callahan — how strange would that have been?)

In most cases, I think it’s just better to read a story or novel before viewing its screen version. That way you can keep an open mind, and paint your own pictures of the folks involved.

One final point, on the too-much-physical-description issue. Many readers feel that it’s actually a compliment to them, by the writer, when they’re given the freedom to furnish their own images of the characters. It’s as if the writer is acknowledging the fact that readers are smart enough not to have to be told every single detail.

Another King quote: “Description begins in the writer’s imagination, but should finish in the reader’s.”

Sounds good to me.

It’s disconcerting when I’ve pictured a character in mind and the film director casts someone entirely at odds with my mental image. A pleasant exception was the casting of Kathleen Turner as V.I. Warshawski who’d come off as distinctively masculine in Paretsky’s series.

Robert Urich actually put me off from starting the Spenser series.

As for my friends in the RWA, I’m told looks are paramount. Protagonists are described in loving, religious detail. “His cobalt eyes glint like a tall Harrison Ford’s and her fulsome breasts heave like Patricia Arquette’s.” One editor is often quoted for her requirement that breasts and genitals must be sizable. Where would Romance be without LOOKS? Women are so shallow!

… he quipped, riding off into the distance, his frame tall in the saddle, his dusty blond hair blowing in the wind, his muscular legs clasping the body of the horse, its palomino mane flouncing, the white sock of its left fetlock in contrast to …

As I write my mystery, I have very definite images of my characters. I used WriteWayPro, where I have an opportunity to add images to my character profiles. While I know that short of saying this character looks like this person, I am conveying my vision of my characters in my writing. Where the reader goes with that is up for grabs.

Hi John,

Funny you should bring this up right now. April is the month of The Big Read, and here in New York City, the book for the Read is the Maltese Falcon. I haven’t read it in more than thirty years, so I decided to re-read it. Surprise! The first paragraph stopped me cold. I had to think for a while until I could settle in and read again.

“Samuel Spade’s jaw was long and bony, his chin a jutting v under the more flexible v of his mouth. His nostrils curved back to make another, smaller v. His yellow-grey eyes were horizontal. The v motif was picked up again by thickish brows rising outward from twin creases above a hooked nose, and his pale brown hair grew down from high flat temples–in a point on his forehead. He looked rather pleasantly like a blond satan.”

I started again and have now met Miss Wonderly, Joel Cairo and of course Effie.

Even recognizing that Sam (Samuel!!!) Spade is such a famous movie character that he can only look like Bogart in most minds, this is way too much description for me. I don’t like to read physical description, I like to get a sense of the character and build him/her in my imagination. Most of the time I don’t care what they look like. I just know that character A is a jester or character B is too quiet.

In writing I try to give a sense of my characters personalities rather than their physical appearance.

Terrie

Jo Dereske says that a lot of people have complained to her “you shouldn’t have made (her main character) Miss Zukas so unattractive!” She has never described Miss Zukas physically.

I read somewhere that the original actor invited to play Lieutenant Columbo was…Bing Crosby.

Rob — Not that it matters, but here are some more early choices for roles, that (thank God) didn’t materialize:

John Travolta — “An Officer and a Gentleman”

Rock Hudson — “To Kill a Mockingbird”

Ernest Borgnine — “The Godfather” (Vito Corleone)

Charles Grodin — “The Graduate”

Tom Selleck — “Raiders of the Lost Ark”

Shirley Temple — “The Wizard of Oz”

George Raft — “Casablanca”

Tom Hanks — “Batman Forever”

Burt Lancaster — “Patton” and “Ben-Hur”

Jimmy Cagney — “The Adventures of Robin Hood”

And something that’s almost as interesting, to me, is that some of our current mystery writers started out in other genres: Janet Evanovich wrote romance, Elmore Leonard westerns, Lawrence Block erotica. Glad they saw the light.

W.C. Fields was originally set to play the Wizard in “Wizard of Oz.” I love Fields but can’t you just imagine: “Remember my sentimental friend, your heart is not measured by how much you love but how much you are loved by others. Speaking of measuring, I have this magical flask right here…” Bless him and Frank Morgan.