Monday, April 14: The Scribbler

I wrote the following over a year ago for a previous incarnation of The Scribbler, and stumbled upon it while looking for something else. It struck me as appropriate for Criminal Brief, so I brushed it up — I can never read anything I’ve written without rewriting it, even just a little — and here it is. Dissenting opinions are strongly encouraged. One of the points of a blog is to stimulate informed debate, after all.

MYSTERY SHORT STORY WRITER DISSES PAPA

by James Lincoln Warren

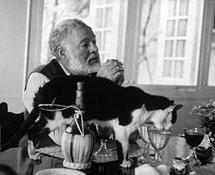

Regular Gentle Readers will know that I am not a fan of Ernest Hemingway’s at all, that I believe F. Scott Fitzgerald’s reputation is as bloated as a six-day-old cadaver in the Outback, and that I mostly regard William Faulkner as a verbose, perverted old windbag. But that’s not what I want to write about.

Regular Gentle Readers will know that I am not a fan of Ernest Hemingway’s at all, that I believe F. Scott Fitzgerald’s reputation is as bloated as a six-day-old cadaver in the Outback, and that I mostly regard William Faulkner as a verbose, perverted old windbag. But that’s not what I want to write about.

The reason I bring up the Big Three of High School American Literature is because of a famous and almost certainly apocryphal folktale involving all three. The story goes that Hemingway bet the other two ten bucks he could come up with a novel in six words, and won with “Baby shoes for sale, never used” (or a variation thereon), hereafter to be referred to as BSFSNU. (I was tempted to shorten that even further to BS, but resisted.)

I find this anecdote utterly loathsome. First of all, you just know that Hemingway must have already written the six words before he proposed the wager, clearly marking the bet as the act of a desperate drunken scoundrel looking for a sucker to pay for his next snort—it was a bar bet, after all, supposedly at the Algonquin.

Secondly, the story is almost certainly not true, and contumeliously portrays Hemingway, a generous man and great writer (even if I hate his telegraphic prose and find his portrayals of women as flat as cardboard), as a desperate drunken scoundrel looking for a sucker to pay for his next snort.

Thirdly and most importantly, the six words are not remotely a story.

What’s this? you incredulously ask. Not? But of course it’s a story!—all the elements are there—the poignancy—the character development—the clever twist at the end—well, all right, so there isn’t really any character development, but still—

O Gentle Readers! Please remember that Hemingway was trained as a journalist. Those six words aren’t a novel. They aren’t even a short story.

They’re a headline.

Here are six variations consistent with Hemingway’s six words, of only six words each themselves, each exhibiting a different universe of facts:

(1) Normal shoes don’t fit polydactyllic infants.

(2) Hysterical pregnancies render shower gifts useless.

(3) Infants clothing store has clearance sale.

(4) Shoe fetishist’s investments tank, liquidates collection.

(5) Junior wasn’t born yesterday, you know.

(6) We just call Fifi our baby.

And here’s a special bonus round:

(7) Not ANOTHER pair! I hate Christmas.

BSFSNU is not a story.

A story must contain a unique universe of facts, which, as I have just demonstrated, BSFSNU does not. A story has to have exposition, development, climax, denouement, and resolution. That’s five words right there. BSFSNU doesn’t have any of those things.

Which is not to say that BSFSNU can’t teach us a thing or two about good writing—all right, I admit it, I actually think that A Moveable Feast is a phenomenal book and that Hemingway was an excellent short story writer, if not on the same level as, say, Anton Chekhov; it’s only Hemingway’s novels I consider stenchful—because it demonstrates the power of suggestion, which is one of the most important techniques in the verbal arsenal. But it doesn’t teach us anything at all about structuring a complex tale, as it proposes.

This is the sort of urban legend that proposes to convey some sort of unconventional wisdom but really does more damage than good. It reminds me of the story supposedly related by Sir Ernest Rutherford of how the young student Niels Bohr responded to a test question on how to determine the altitude of a building by means of a barometer. (The way this story is usually told, the student is left anonymous until the end and the revelation of his identity serves as the punch line — “That student was none other than NIELS BOHR, who would later create the model of the atom and win the Nobel Prize for Physics!” — which I regard as a cheap trick. Hidden identity can be an effective story-telling device — recall Rob Lopresti’s fabulous “The Hard Case” — but pyrotechnics should only be handled by experts.)

This is the sort of urban legend that proposes to convey some sort of unconventional wisdom but really does more damage than good. It reminds me of the story supposedly related by Sir Ernest Rutherford of how the young student Niels Bohr responded to a test question on how to determine the altitude of a building by means of a barometer. (The way this story is usually told, the student is left anonymous until the end and the revelation of his identity serves as the punch line — “That student was none other than NIELS BOHR, who would later create the model of the atom and win the Nobel Prize for Physics!” — which I regard as a cheap trick. Hidden identity can be an effective story-telling device — recall Rob Lopresti’s fabulous “The Hard Case” — but pyrotechnics should only be handled by experts.)

Not wanting to be constrained by conventional approaches, Bohr is said to have answered the question by proposing using the barometer as a plum bob and measuring the length of the rope, or by dropping the barometer off the roof and timing its descent, or by using the height of the barometer as a ruler, or by swinging the barometer as pendulum and timing the pendulum’s period, or by using the barometer as a bribe to the building’s super to provide the building’s dimensions. The one answer that Bohr did not apparently want to give is the obvious one of using the barometer to measure atmospheric pressure at the bottom and top of the building. When asked why he was being so perverse, the young Bohr replied that he was weary of high school instructors trying to teach him how to think.

This story is objectionable for similar reasons to BSFSNU. First of all, by his perverse insistence on not providing the knowledge that his professor was obviously examining for, it shows a snotty insensitivity and undeserved lack of respect for the instructor. I am never in favor of showing teachers disrespect, even if they demonstrate small pedagogical gifts. Teachers bear the burden of civilization’s survival, after all.

Secondly, the story is categorically false, and contumeliously portrays Bohr, a generous man and a great physicist, as a snotty, insensitive teenage clod who had no respect for his teacher.

Thirdly, its trite “thinking outside the box” moral is insultingly simplistic — before one demonstrates how well one can think outside the box, one ought to demonstrate that one knows what’s actually inside the box. Besides which, of course, the whole “inside/outside the box” metaphor is an unforgivable cliché.

Mere wit should never be confused with wisdom.

Hadn’t heard the Boher story! Ironically I’m not much of a Hemmingway or Fitzgerald fan but I love the work of several writers who are! (You are forever spared my horrid pastiche of a Hemingway-esque hunter told in the style of H.P. Lovecraft. [It was hot, and the dark smelled of eldrich fetor, but that was good…]}

Secondly, the story is almost certainly not true,—-

You had me until the “almost certainly not”—

I began to pace within my box trying to piece the conundrum and found myself, yes, found myself peeking over the box!

In my wisdom I could not define nor place those three words together to prove to me this was other than your opinion, though strongly stated. And opinion is great, I just couldn’t decide what you really meant.

I decided to go with wit and get out of that box and take a look-see (I learned that term from Lonesome Dove).

I finally decided I didn’t care other than it threw me while reading and Hemingway could surely write a long and wordy novel about that poor baby who died at birth and his wife (oh wait, better yet lover) was alone, without money (it had been squandered on drink, lust and the World Poker Tour). The poor baby died of SIDS and the only thing lover had was a pair of red slippers for baby boy (she was sure it was a girl but didn’t have funds for a sonogram). The dirty rotten drunk sobered and with his winnings and newfound love for this woman and child, set off to conquer his demons with her and win her back. But wait, there’s another man courting this lovely woman with no baby in sight. He truly believes she aborted his child and took up with this man and murdered them both in a rage (he had a temper you see, yet under control). Later, he finds the ad in the paper and begins to ask questions. Ruh roh.

I kind of think it’s fun outside the box! I’m back on the inside now.

Anyway, I enjoyed your article. Almost certainly not true–but truly I did.

Thanks!

At the great Rose Polytechnic (American’s #1 undergraduate science/engineering school you’ve never heard of), freshman were given the barometer story (without the Bohr reference) as an exercise to see how many solutions they could invent.

Students came up with perhaps 18-20 ideas– some bright, some silly– among them:

I think the story’s more fun without the Bohr connection.

I loved the Bohr connection. No one has yet mentioned that besides inventing the barometer, Neils Bohr was a great Dane.

I can’t read about drunken mystery writers without thinking of Raymond Chandler. The Wikipedia (users beware) has a posthumous posting on his life that reaffirms my initial impression that he must have been living on alcohol. The stuff reportedly separated him from salaried employment. I read a couple of his abridged, two-cassette mystery stories when I started with audiobooks in 1990. Chandler seemed to have two personal preoccupations that leaked into his novels: one with quaffing double Gibsons, and the other with women’s legs.

I had some neighbors of about my age who drank a lot by anyone’s standards – no booze before 5 (AM that is). They brought me up to speed on the Gibson, a martini made with an onion instead of an olive. We can only presume the double was invented to save washing twice as many glasses.

As a medical professional, I can’t believe the Wikipedia’s aspersion of him being a closeted homosexual based on reports from his last two wives. Maybe a “leg fetish,” but not penis envy. My curbstone diagnosis would favor E.D. as a result of the industrial quantities of gin, onions and nicotine he must have consumed over a lifetime.

Pictures of Chandler, including the one in Wiki, all show him with a pipe in his mouth. Soaking your liver in alcohol and your lungs with tobacco smoke should bring about an early death, but Phillip Marlowe’s inventor made it to a ripe old 70. Go figure.

Other than wondering what the heck contumeliously means, I can only say I have reached the age of 82 thanks to smoking a pipe every waking hour and consuming a six-figure number of gibsons.