Monday, July 20: Mystery Masterclass

I am still in South Africa. Therefore, this week I offer you this special treat from one of my favorite mystery short story authors—the reasons for which should be obvious.

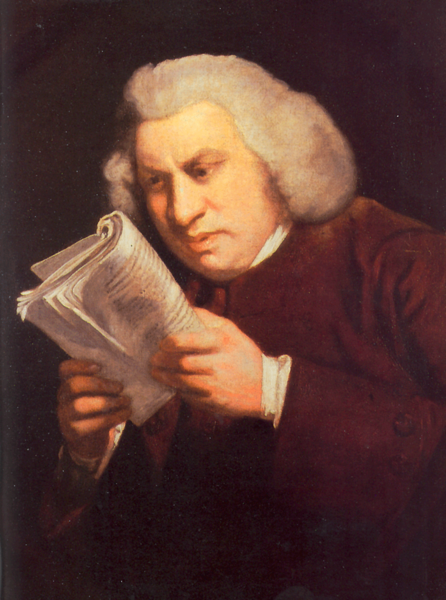

The first mystery author to use an actual historical personage as a fictional detective was the late Lillian de la Torre Bueno McCue (1902-1993), who chronicled the exploits of Dr. Sam: Johnson for Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine beginning in 1944. It’s embarrassing, but I wasn’t even aware of Lillian de la Torre when I first planned my own 18th century detective—I thought the period was under-represented! So I stumbled upon the exact turf of the most successful historical mystery writer before Ellis Peters. Well, you know what they say as to rushing in where angels fear to tread. I was lucky.

In 1985, in the Foreword to the third collection of Dr. Sam: Johnson stories, The Return of Dr. Sam: Johnson, Detector, Ms. de la Torre explained how she was inspired to turn the Grand Cham of English Literature into a private investigator. The following has been excerpted from that essay. The title is mine, since somehow “Foreword” didn’t seem to cover the material well enough.

—JLW

HOW DR. SAM: JOHNSON BECAME A DETECTOR

copyright 1985 by Lillian de la Torre

by Lillian de la Torre

Once upon a time I had an argument with my husband, the Professor. I usually forget an argument as soon as it is over, but I have never forgotten this one, for its consequences were far-reaching.

The Professor was decrying my favorite reading, detective stories.

“Detectives, bosh!” he snorted. “Drawling dilettantes, cute brides, sententious Chinamen, dear old ladies-next thing, I suppose, a police dog!”

“There’s been a police dog,” I admitted. “Granted, if the detective’s flimsy, the story’s flimsy. But if the detective is a solid and many-sided personality, like-like, for instance, Dr. Sam: Johnson in Boswell’s great biography—”

As the words left my lips, I knew what I had. Here was a real man as versatile and various as any fictitious detective, just and humane, with wide-ranging interests and flavorful personality; a man of undaunted valor, keen intellect, and scientific curiosity. What a detective he would make! And he came equipped with his Boswell, the only original Boswell, a fascinating character in his own right, with his amatory exploits, his flair for sensation, and his gift of observation.

And the two friends flourished in the English Age of Reason, the 18th Century, a time of awakening scientific curiosity and humanitarian regard for the fate of the individual. As Howard Haycraft has pointed out, detective interest could hardly have come along sooner.

As the 18th century advanced, Bow Street began to know honest magistrates like Henry Fielding, ‘the novelist. Later his brother Sir John Fielding flourished, the famous “Blind Beak of Bow Street, “ with his sturdy second in command, Saunders Welch. These latter were Dr. Johnson’s friends, and from them he learned about crime. “Johnson, who had an eager and unceasing curiosity to know human life in all its variety, told me,” records Boswell, “that he attended Mr. Welch in his office for a whole winter, to hear the examinations of the culprits: “

The 18th century was rich in picturesque culprits to take the spotlight, highwaymen and footpads, frauds and forgers. Dr. Sam: Johnson interested himself in the forgers and the frauds. He even wrote the last dying speech and confession of one of them, Dr. Dodd, the fashionable “macaroni parson,” who had augmented his emoluments with some quiet sleight-of-pen work, and was hanged for it. Visiting Bristol, he studied the literary forgeries of Thomas Chatterton, the “marvellous boy,” and pronounced him, correctly, both a fraud and a genius. When “Ossian” Macpherson produced “an ancient epic poem translated from the Gaelic,” Dr. Johnson immediately perceived it to be a contemporary fake, and denounced it as such. “Do you think,” demanded a believer, “that any man of modern age could have written such poems?” “Yes, sir,” replied Johnson contemptuously, “many men, many women, and many children!” Naturally Macpherson, a surly Scot, waxed irate. When he sent Johnson a threatening letter, the sage replied truculently, “I will not be deterred from detecting what I think a cheat by the menaces of a ruffian.” (Note the word “detecting.” He knew what he was doing.) It was for defence against Macpherson’s threats that he purchased his famous oaken stick.

His curiosity about the world ranged wide. He gratified it by performing chemical experiments in Thrale’s garden shed, with such enthusiasm that Mrs. Thrale feared he would blow them all up. He was open-minded enough to seek evidence of the supernatural world; but when he probed the matter of the Cock Lane Ghost and wrote up the results, he was forced to conclude that Scratching Fanny was no ghost at all. “He expressed great indignation at the imposture of the Cock Lane Ghost,” says Boswell, “and related, with much satisfaction, how he had assisted in detecting the cheat.” (Detecting again!)

James Boswell, Dr. Johnson’s disciple and biographer, was by profession a lawyer. He too was fascinated by the world of mystery and crime, but his point of view was more sensational. His approach to a forger—the intriguing lady forger, Mrs. Rudd—was to make love to her and take her along to ride the circuit with him. He haunted executions with “horrid eagerness,” and badgered condemned men to reveal their tremors. He was avid for such sensational experiences, and wrote them all up, in his letters, in his diaries, and in the newspapers.

Like Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson a century later, Johnson and Boswell perambulated the most facinating of cities, London. “He who is tired of London,” observed Dr. Johnson, “is tired of life.” Theirs, however, was a London with a difference—not the fog-bound metropolis that Conan Doyle etched, but the sparkling city that Canaletto painted.

Such were the men, and such was the setting, that flashed into my mind that day. Soon plots of mystery and detection began to form theselves around many of the striking events, the picturesque scenes, and the eccentric personalities of that fascinating time; and Dr. Sam: Johnson as detector dominated them all.

To the best of my knowledge, I was the first but not the last to weave such stories around a real historical character for a detective. I was certainly the first to select a historical character who already had his Boswell to narrate his adventures.

Writing as James Boswell, I found it a challenge to use the rhetoric and vocabulary that he would have used, and no other. He made a point of adhering to certain old-style spellings, and so do I: Dr. Johnson’s words come sometimes from the record, sometimes from my imagination as I conceive he would have spoken.

Boswell said of himself that he had become “impregnated with the Johnsonian aether.” I should like to think that the “Johnsonian aether” permeates’ my tales, and that in fictitiously presenting Dr. Sam: Johnson as a detector of crime and chicane, righting wrongs and penetrating mysteries, I have made him act in a manner that is always consistent with the real man as he walked the earth two hundred years ago.

I know you’re not around to read the comments, James, but having stumbled upon de la Torre’s stories, I wasn’t previously aware of who she was or the background of the series until your article.

I knew Lillian quite well by correspondence. She was a wonderful, talented, and (in her later years) courageous lady. Doug Greene

This may not be the right place to comment – bur if you are in South Africa you should pick up an anthology of short stories by South Africa’s leading mystery writers. It is called Bad Company, published by MacMillan.

The Dr. Sam: Johnson series was, for a while, one of the longest-running series of mysteries. (And an Irony: The Great Lexicographer wound up adding another word to the dictionary—“boswell.”)