Monday, August 10: The Scribbler

CHOICE CUT

by James Lincoln Warren

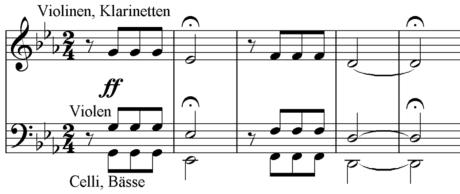

John’s article on Saturday brought up the topic of film composers, and that stimulated a little introspection and reflection on my part. I spent the plurality of my college years as a musician and even attended the Mannes College of Music in New York City as a conducting major for two of them. I left Mannes just before they threw my ass out — actually, they threw my ass out anyway, because I was so angry when I departed that I didn’t bother to tell them I wasn’t coming back. I received notification from Mannes that I was no longer enrolled two weeks into the fall semester at another college. I laughed and cried when I read the letter, hiding in my parents’ garage because I didn’t want my reaction to be witnessed by anybody when I opened the fatal missive.

All that was a long time ago, and believe me, my anger has long since dissipated. One of my best friends is now on Mannes’s faculty. Most (but by no means all) of my failure as a student there was my own damn fault anyway, and holding a thirty-year grudge is hard work. (To be honest, my anger had bid adieu only a couple of years after the event. I visited the Mannes campus shortly after I joined the Navy and was affectionately treated by everyone there as if I were a distinguished alumnus.)

When I have occasion to tell people of my musical education, I frequently get asked why I quit, especially since classical music is still my greatest, albeit avocational, passion. I guess most people don’t realize that this is a deeply personal question, but it is. The closest simple answer to such a complex query is frankly that I lacked sufficient talent to fulfill my ambitions, a fact not all that easy to confess to relative strangers — nobody relishes exposing their weaknesses, and the failure to recognize one’s own true potential connotes other, more profound, weaknesses, among them a lamentable lack of self-awareness exacerbated by an unattractive touch of arrogance. Not that I worry about such things now. It’s a lot easier to face this sort of thing in one’s 50s than in one’s 20s.

And this thought led to another link in the chain of experience, to wit, the realization that life is a mix of the choices we make and the choices that are willy-nilly made for us. Hardly an original sentiment, I know, but it strikes me that an understanding of this essential fact is indispensable to the art of story-telling, especially of the crime variety.

The victim of a crime has no choice, but the commission of the crime may be facilitated by the choices the victim has made, without knowledge or regard to the possible consequences — either it goes to motive or to opportunity. A jealous husband kills his rival because the rival chose to compete for the favors of his wife. A woman is assaulted in a dark alley because she went drinking at the wrong club. An overbearing boss pushes his long-suffering employee beyond endurance. And so forth.

All crime fiction treats with either the application or the deprivation of justice, or with both, in all justice’s variegated forms between legal and poetic. That’s where the drama lies. The drama is manifested in the choices for good or ill that the character makes — it’s a truism in story-telling that the reader should be made more aware of the character’s strengths and weaknesses than the character is himself. When a character makes a bad choice, the reader should feel a sense of alarm, unless the consequences of that choice are intended to come as a surprise or shock. Don’t climb up the stairs into the dark attic! Give the mysterious bag full of money to the police! Don’t ignore the stranger’s desperate plea for help!

Alternatively, a character may be forced into a situation entirely not of his own making. Fate, if you will. This is the classic formula for the thriller — Roger O. Thornhill flags down a bellboy at the Plaza Hotel and is thereby mistaken for government agent George Kaplan by two ruthless spies, setting off a dance of danger and death that eventually culminates in a desperate life-or-death pursuit on Mount Rushmore. The only choices Roger can make in the interim go directly to survival, and you can’t get much more dramatic than that. One false step and it’s adios, amigo. (Speaking of, everyone is relieved when the vile Leonard is taken out by a sniper just in time.)

For years, I’ve been fond of saying with regard to genre fiction that science fiction is a literature of ideas, but that crime fiction is a literature of behavior. That’s probably a tad superficial. It seems to me now that it’s also a literature of principles, of behavior in context. I’ve also said that we mystery writers have only one basic plot, and I still think that’s true, but to our advantage we have a plot that embraces an infinity of personal choices. Maybe that’s one reason why I love to write crime stories. It lets me explore consequences without actually having to live them.

Deborah asked last week, “What if … ?” She was reflecting on the transitory nature of life, but that is the indispensable question that drives all fiction. The important thing is to ask it before it has already been decided.

I was a fair musician, but I was no Arturo Toscanini. I don’t regret leaving that life behind in the least, especially when I think of how rich my life has been since. One of things I learned from that whole life episode is that you are not what you do, and if you confuse being with doing, you’re setting yourself up for a lot of suffering. Another tick in the plus column is that it endowed me with a lot of great stories to tell. If the Gentle Reader ever joins me for a cocktail at the bar, and the Gentle Reader is always invited, ask me about how I met Leonard Bernstein. If that anecdote doesn’t make you laugh and inspire you with wistful imaginings, nothing will.

In other news …

David L. Ulin, book editor for the Los Angeles Times, has a wonderful piece in Sunday’s paper on the challenges facing people who love to read. In the print edition, it was headlined “Finding your focus”, but online it’s led by “The lost art of reading”. In any case, here’s a link.

Victim….Jealous husband…..why didn’t he shoot his wife? She chose as well. Just asking…..OR himself since his rival must have been more favorable to his wife….OR…..that’s why I like fiction crime or mystery stories. Such possibility.

Music….Wille, Mellencamp and Dylan entertained me last night. I love Willie. Great songwriter, entertainer, guitarist. I’d not paid much attention to Mellencamp but he knew his audience, great band, great enternainer.

Bob Dylan I think must be a recluse aHole in his life. I went mainly because I wanted to see him before one of us died. I’ll continue to buy his music because he is such a wordsmith. His stage presence sucks!

My roundabout babbling is that music is a very important part of my life and I have an eclectic taste.

Since John’s article and now this one, I wonder what a composer, or songwriter would do with a fiction genre.

Sure would be interesting, especially those that have a way with words.

So, about Berstein…..

Thanks for telling why you are so knowledgable about music. Thanks, too, for the link to the excellent article by David L. Ulin. It made me aware that I have been having the same problem recently. I can’t seem to settle back with a book the way I did all of my life. The answer is beyond my ability to analyse, yet I wonder what this age of instant information and constant contact is doing to us.

It would be interesting to hear your thoughts on Ulin’s. What if any effect will this have on the novel versus the short story?

As is true of almost everything, Ulin caused me to think back to combat during WWII. Bill Mauldin had a cartoon in which Willie and Joe were wearily hiking along a road and Willie said, “The trouble with you, Joe, is you carry too much extra weight. Throw the joker out of your deck of cards.” This was appreciated by infantrymen who wouldn’t even carry a toothbrush,yet a great many had a paperback book in a pocket. At quiet moments a great deal of reading took place. I suppose a psychiatrist or psychologist could explain this, or try to. Hell, I can’t even explain where all those books came from.

JLW, I stole your link and copied it on a message board I visit every day. Also told them to read Criminalbrief, something I do quite often. A lot of them do so.

alisa writes: Victim….Jealous husband…..why didn’t he shoot his wife? She chose as well. Just asking …

Why, yes. Exactly.

Dick writes: I suppose a psychiatrist or psychologist could explain this, or try to.

As it happens, my Dad (also a WWII veteran grunt, although he was a Marine in the Pacific — he’s a year younger than you are, and started his service in 1945) is a psychiatrist, or rather a retired one. One of his specialties is Post Traumatic Stress. I’ll ask him. Dad’s explanations of human behavior always make good common sense.

This may be your most personal column… and I admire it.

Don’t be daft. All writing is personal writing. If you want to admire something, admire my engaging prose style.

Dick, here’s what my father has to say about reading books in World War II:

Jim, my main recollection of books, looking back approximately 65 years ago, was on troop ships. There always appeared to be an abundance of paperback books aboard ships. I know the sailors and marines didn’t bring them all on board, and I think they were donated by the Red Cross and other organizations. I have an afterimage of some of them having ink stamps “donated by such and such an organization”. I don’t recall doing much reading myself as I spent most of my time field dressing and field dressing and field dressing and cleaning my M1 rifle and other gear in an obsessive manner most of the time. We were in the middle of the jungle on Guam and I don’t remember ever seeing a book there or time to read one if we had one. When we got to China to what was then called, “Peking”, I remember there was a small library in the Italian Legation run by the Red Cross, where books could be checked out. Many of my fellow marines carried a New Testament with them. I still have mine with a Marine Corps emblem stamped on the front cover. It was donated by the American Bible Society, so I guess there was no conflict between church and state, and everything was constitutionally correct. If many of the Army grunts carried paperback books in their pockets, they were obviously more literate than we were. As a psychiatrist, I would not even want to start analyzing this difference. Sorry that I can’t contribute more than these weak memories, Jim.

It’s worth mentioning many paperbacks published during the war were in an elongated style, perhaps 3 to 3-1/2 inches high and 5 or 6 inches wide.

Wow! James, your post and the personal info. from your Father are wonderful to have! I know I have (or have seen) a paperback from the WWII years with a notice on the back that the book can be mailed to an American serving overseas. I stopped mid-post and wrote down your words about science fiction and crime fiction. I’m more a music lover than player (Oscar Levant RULES!!!!) but I’ll take this opportunity to mention British composer Bruce Montgomery who wrote scores for film, and also(under the name Edmund Crispin) wrote the novels and short-stories about Gervase Fen, Oxford Don and part-time detective. A music-lover who seems to know he’s a fictional character.

Conductor, play us out, maybe with a Gabrielli canzon???

Thanks for your father’s comments, JLW. Tell him I thought it was common knowledge that we beetle crushers were more literate than gyrenes and gobs. Unlike his M-1, mine received little attention but I was a bullet polisher. At ever opportunity I would remove the clips from my cartridge belt and wipe every speck of dust from each bullet. I feel confident in saying I had the cleanest bullets in Europe. Please don’t ask why this seemed important to me.