Wednesday, August 19: Tune It Or Die!

INCIDENT IN TACOMA

by Rob Lopresti

Here is a sort of mystery story, about a very famous mystery story. I’ll be interested to see if you figure out the destination before we get there.

Michael S. Sullivan has a terrific article in the Spring issue of Columbia, a magazine about Northwest history. He tells us about several incidents in the history of Tacoma, Washington, and makes a pretty good case that they helped shape one of the most famous passages in American mystery fiction. (The article is not available on the web, but an earlier related piece by Sullivan is here.)

Briefly stated, here are the facts:

- In November 1920 a World War I veteran named Samuel Hammett, suffering from tuberculosis, was admitted to a new hospital in Tacoma.

- In December a police officer, investigating an armed robbery, ordered a man in the street to stop. When the man ran away the policeman fired a warning shot into the air. Then he fired at the runner, who was 100 yards away. According to Sullivan: “The bullet sparked on the wet street like a flint on stone and ricocheted up, mortally wounding the man.” The victim was a carpenter, out for an evening stroll. His name was Samuel Hamblet. The policeman – who soon left the force – was W. H. Craft.

- A month later the Scandinavian American Bank, the biggest in Tacoma, went bankrupt, apparently due to crimes committed by its president. The 15-story headquarters for the bank was left unfinished, its naked beams showing, for nearly a decade.

Black bird calling

Some of you are probably seeing the shape these jigsaw puzzle pieces must form. Here’s the deal …

Samuel Hammett’s lungs cleared up and he started writing fiction based on his experiences with the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Of course, he wrote under the name Dashiell Hammett.

In Chapter 7 of his novel The Maltese Falcon, Hammett wrote a tale that stands out so far from the rest of the book that commentators have given it its own name: “The Flitcraft Parable.” If you only saw the movie, sorry, this is the one important piece John Huston left out. It’s only about four pages and you can read it here. There is even a comic book version by Stan Shaw.

Briefly, Sam Spade tells his client Brigid O’Shaughnessy about a man named Flitcraft who lived in Tacoma in 1922. One day he strolled past an unfinished office building and was almost killed by a beam tumbling down eight floors. It missed him, but it chipped off a piece of the sidewalk that hit him on the cheek and scarred him for life.

Why this incident matters to Spade, you will have to read the parable to find out. But you can see why Sullivan thinks that Samuel Hammett can hardly have missed hearing about the violent fluke of fate that killed a man named Samuel Hamblet, and chose to incorporate part of it into his story.

But I don’t think Flitcraft’s name came from Officer Craft. In the 1920’s the actuarial book that insurance companies used to calculate the risks of deaths and accidents was the Flitcraft Table.

The moral of the story

People have been arguing for eighty years about the Parable, and why Spade chose to tell Brigid this story, out of all the cases he could have described (or why Hammett chose to have Spade share it with us). One book analyzing Hammett’s work is even titled Beams Falling. I’m not going to try to solve that question for you.

But I highly recommend you read Sullivan’s article. And if you have never read The Maltese Falcon, my word, what’s keeping you?

Another thread from the web

In the discussion of bally-hoo that followed Steve’s column I pointed out a use of the word in Herman Melville’s 1850 novel Omoo. I found it by looking in Making Of America, an amazing website that contains full-text books and articles from (mostly) the nineteenth century. MOA is in two distinct halves, maintained by Cornell University and the University of Michigan. For example, I just searched the Cornell site (which I think is easier to use) for the phrase “private detective” and got fifteen hits. Rearranging them by ascending date I found that the oldest was this passage in a book called Sunshine and Shadow in New York, by Matthew Hale Smith, published in 1868.

The success of detectives in criminal matters, as a part of the police, has created a private detective system, which is at the service of any one who can pay for it. It is a spy system, — a system of espionage that is not creditable or safe. Men are watched and tracked about the city by these gentlemen, and one cannot tell when a spy is on his track. A jealous wife will put a detective on the track of her husband, who will follow him for weeks if paid for it, and lay before her a complete programme of his acts and expenditures. If a man wants a divorce, he hires a detective to furnish the needed evidence. Slander suits are got up, conducted, and maintained often by this agency. Divorce suits are carried through our courts by evidence so obtained. Sudden explosions in domestic life, the dissolution of households, and family separations, originate in this system. It is not very comforting to know that such shadows are on our paths.

So, beware.

Rob — Great “story behind the story”! I remember Spade telling Brigid about the Flitcraft incident, but never knew the rest.

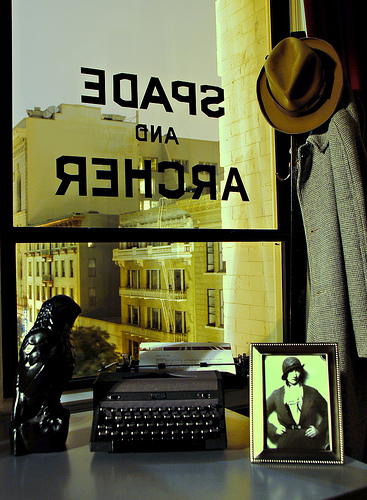

Also, I think the view of/from Spade’s office is one of the best illustrations ever used in s CB piece.

Rather a rude description of a PI, but it was written in 1868. Pinkerton didn’t take domestic cases. Reminds me of a story, of course.

One day half a dozen of us were sitting around in the room for ops waiting for an assignment. The office of one of the assistant managers was next door and the walls were paper thin.

A woman came in and begged the AM to take on the job of checking up her husband. She said, “Here’s a check for a thousand dollars and a plane ticket to Miami.”

He explained over and over that the agency didn’t do that kind of work. When she finally gave up and left there were six of us tempted to chase her down the hall yelling, “I’ll do it! I’ll do it!”

No one did, of course.

Y’know, Rob, I haven’t read “The Maltese Falcon.” Yeah, I saw the movie, but I need to read the book! (I may stop with Ch. 7!)

Jeff,

at least read to chapter 9. You’ll find out who trashed Brigid’s hotel room. (The film says it happened but doesn’t tell you whodunit…it’s a surprise). And then there is the Fat Man’s daughter.

John-

As usual the illustration was located by our fearless leader, JLW.

Dick-

Great story, thanks.

Owwww! I meant I may “start with chapter 7!” Yipes! I’d better start with Ch. 1!

One of the best articles, Rob.