Monday, May 26: The Scribbler

TWO KINDS OF STORIES

by James Lincoln Warren

There are two kinds of people in the world, those who believe there are two kinds of people in the world and those who don’t.

—Robert Benchley’s “Law of Distinction”

I was at a cocktail party some time ago and was in conversation with someone I had just met there. When during the regular course of chatting about our respective selves I revealed that I was a writer of short crime fiction, I got an unusual reaction. Usually, the person receiving this gem of knowledge will say something along the lines of, “Have I seen any of your work?”, to which the most honest answer is, “Not unless you subscribe to Alfred Hitchcock or Ellery Queen,” but this time I got a little grenade tossed into my lap instead.

I was at a cocktail party some time ago and was in conversation with someone I had just met there. When during the regular course of chatting about our respective selves I revealed that I was a writer of short crime fiction, I got an unusual reaction. Usually, the person receiving this gem of knowledge will say something along the lines of, “Have I seen any of your work?”, to which the most honest answer is, “Not unless you subscribe to Alfred Hitchcock or Ellery Queen,” but this time I got a little grenade tossed into my lap instead.

“I don’t like short stories,” quoth my newly-made acquaintance. “I prefer character-driven fiction, and so novels. Short stories are all plot-driven. You don’t have room in them to truly develop satisfactory characters.”

At which the Gentle Reader may be excused for imagining I went into an apoplectic seizure—but I didn’t. I maintained a cryogenic calm, prevented my glass of vin rouge ordinaire from shattering in my hand, and blurted, “What the hell are you talking about?”

Yes, Virginia, there are two kinds of people in the world: those who believe that fiction is plot-driven, and those who believe that fiction is character-driven. And they are both wrong.

To compound matters, members of the latter camp have a palpable sense of superiority. They labor under the illusion that they alone have Good Taste. You may hear them say, with a spiritual if not physical sneer in their voices, “Faulkner said that the only thing worth writing about is the human heart in conflict with itself.” 1 Talk about ostentatious caca.

What exactly do “character-driven” and “plot-driven” mean, anyway?

I’m glad you asked, because usually when these terms are thrown about they have no more meaning than any other literary buzz words. What people usually intend by them is that “character-driven” pieces are those which are primarily concerned with the internal emotional conflicts of the characters, whereas a “plot-driven” story is one in which character development is minimized in favor of action—the sequence of events described in the story. Now, this is not actually what these terms mean at all.

A character-driven piece is one in which the action is driven by the decisions made by the characters. A plot-driven piece, by contrast, is one in which external events drive the behavior of the characters. In other words, they are both matters of technique in terms of story-telling. Being only matters of technique, one cannot be superior to another, and the gifted story teller—and the good story—will make use of both. Take Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace for a spin to see what I’m talking about.

So what do you call a story that does concentrate on the internal conflicts of the characters instead of the action? I would call that a character study. And I would call a story that ignores character development in favor of action simply a story with bad characterization. For the truth of the matter is that many classic “plot-driven” stories are rich in character—Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped immediately leaps to mind—and many “character-driven” stories tell of compelling events—à la Michael Connelly’s The Last Coyote (my personal favorite among the Hieronymous Bosch novels).

All right, the Gentle Reader says, I get your point, but War and Peace, Kidnapped, and The Last Coyote are all novels. What of your acquaintance’s claim that short stories are too short to allow character development?

Well, this is just nonsense. A serial character in short fiction can be just as complex as any character in novels. Sherlock Holmes is surely one of the most finely drawn characters of all time, but he only appeared in four novels, and in those he’s offstage for large chunks of the story. We know him best from the 56 short stories featuring him. The difference between characterization in a short story and in a novel—and I’m talking about good characterization—is that in a short story, the reader is only exposed to only those elements of the character’s personality that are germane to the story, whereas in a novel, the author may present many facets of the same character. To that extent, novels have an advantage over shorts when it comes to developing three-dimensional characters in a single sitting. But over the long haul, they come out even.

But either way, this has nothing to do with whether the piece is character-driven or not. Last Christmas, I published O. Henry’s classic “The Gift of the Magi” as a yuletide gift to Criminal Brief‘s readers. This is a classic character-driven piece: everything that happens in it is driven by the love the two principals have for each other. The short stories that constitute C. S. Forester’s Mr. Midshipman Hornblower are without exception plot-driven, but at the end of the collection, you have more than a passing acquaintance with young Horatio, his moods and attitudes.

In the end, there are only good stories.

Old TV Series Department

This past Saturday, the DVDs Margaret ordered of the landmark British cop show “The Sweeney”2 arrived and we watched the first two episodes. For those of you who have never heard of it, this was Thames Television’s attempt at a realistic police procedural in 1975. To put things in persepective, in the U.S., we were watching “Baretta”, “Charlie’s Angels”, “The Rockford Files”, and “Starsky and Hutch” among others—“The Rookies” was also on the air, an attempt at a socially conscious cop show. But “The Sweeney” was remarkable in its ground-breaking attempt to de-glamorize television treatment of law enforcement in favor of gritty, hard-hitting drama featuring flawed characters, even if today it seems a little tame in comparison with, say, “Wire in the Blood”.

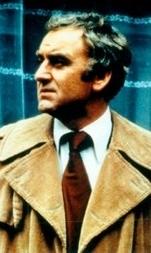

The main hero of the series is Detective Inspector Jack Regan, portrayed by a pre-Morse John Thaw, whose hair had not yet turned white. Although Regan is a less cerebral character than Morse, the two characters have a lot in common—both have sacrificed their personal lives for the job, both are mavericks who have to deal with officious superior officers, both have married sidekicks to serve as factotums and foils, and so forth—and one sees why Thaw was tapped for Morse based on the strength of his performances here.

The main hero of the series is Detective Inspector Jack Regan, portrayed by a pre-Morse John Thaw, whose hair had not yet turned white. Although Regan is a less cerebral character than Morse, the two characters have a lot in common—both have sacrificed their personal lives for the job, both are mavericks who have to deal with officious superior officers, both have married sidekicks to serve as factotums and foils, and so forth—and one sees why Thaw was tapped for Morse based on the strength of his performances here.

Highly recommended.

- Habitual Gentle Readers will know what I think of Faulkner: “a verbose, perverted old windbag.” True, he was one of the writers of the screenplay of “The Big Sleep”, one of the greatest detective films of all time, but his partner was the great Leigh Brackett, a veteran pulp author and Ray Bradbury’s mentor. I’ll take Eric John Stark over Quentin Compson any day. And as far as Mississippi writers are concerned, give me John M. Floyd instead and I’ll be purring like a kitten. [↩]

- The name comes from Cockney rhyming slang: “Sweeney Todd” = “The Flying Squad”, an elite Metropolitan Police unit dedicated to dealing with organized crime. [↩]

Best explanation I have read of plot driven – character driven stories.

Casting modesty aside, the series I’ve been writing for AHMM during the past twenty years provides an example of plot-driven stories that, if read in their entirety, offer complete pictures of even the minor characters.

I agree with Martha Grimes and John Cheever – plot cannot exist without characters, setting, atmosphere and dialogue.

All this talk of plot vs. character reminds me of the thriller vs. mystery debate that was discussed ad nauseam on the internet and at conferences between 2005 and 2007. Who cares?

I love reading characters that interest/intrigue/entertain/scare/etc. me. I believe most people do too, even if they don’t know it. Case in point – talk to avid LAW & ORDER watchers (always the example of plot without character) about their favorite episodes and rarely do they describe the plot before or without describing how the characters acted/reacted. And these are the folks who will swear they prefer plot over character.

Your description of character study as opposed to character-driven is spot on, in my opinion. And those are the stories I prefer reading. And as for short stories being only plot-driven… uh, that person has either never read a short story, or has no idea what plot and character are.

Look at John Cheever’s work or John Lutz’s (to stay within the crime genre) for short stories that are as rich in character as anything with 300+ pages.

Plot vs. character. Who cares? “In the end there are only good stories.” Amen.