Monday, November 16: The Scribbler

BELIEVE IT OR NOT

by James Lincoln Warren

Usually when I write a story that involves contemporary police, I will set it in an imaginary or unnamed city. You could ascribe this to a certain laziness on my part, because it means that I don’t have to do any research into how any actual police department operates and leaves me free to run my imaginary cop shop any way I want. I actually did do some research into a real PD once, for a private eye story called “Cold Reason”, which mostly took place in Beverly Hills and featured a BHPD detective as a minor character. It was important to me to get the details right so that the scenes involving Beverly Hills’ finest would accurately reflect their practices and capabilities—relying on Axel Foley‘s silver screen adventures didn’t strike me as remotely reliable.

My historicals are painstakingly researched, especially for period detail, and I am very careful to make sure that the details of the story conform to the exact dates on which they supposedly took place. When I include an historical person as a character, I try to make sure that his behavior is consistent with the records of his life. But the events in my stories are almost always completely fictional, and I feel no hesitation in introducing fictional characters right into the middle of the mix to assist me in telling my tale.

The one story I’ve written that involved an actual mystery is called “The Iphis Incident” and concerned the notorious disappearance for several days of a celebrated 18th century adventurer and eccentric, the Chevalier d’Éon. In the story, the Chevalier’s friends hire my detective, Alan Treviscoe, to find the Chevalier before his enemies do. When they describe the Chevalier’s appearance to Treviscoe, I borrowed the actual verbiage his friends had used in a newspaper advertisement and used it as dialogue:

“But how am I to find him?”

“That, sir, we leave to you. We can tell you that he was last seen on the afternoon of this Tuesday past, on the 7th of May. He wore a coat, scarlet faced with green with his Cross of St. Louis; had a plain new hat with silver button, loop and band; and with him his sword, but without his cane. He went out alone, leaving orders with his servant to call for him at a friend’s house at ten o’clock, but had not been there, nor been heard of since.”

Everything from the word “scarlet” to the end of the passage was taken verbatim from the advertisement. 1 In that story, I gave d’Éon a completely fictional valet, who was instrumental in the plot.

In the story I’m writing right now, I borrowed the words of Caroline Herschel, (the sister of Sir William Herschel, the discoverer of the planet Uranus, and a formidable astronomer in her own right) from her autobiography and put them in her mouth:

When Caroline returned home, they were treated to further complaints. The local butcher was a thief—“I cannot bring myself to give him our custom, Mr. Treviscoe. He will not give me an honest measure.” The servants were likewise all petty criminals—“When we first arrived, the woman who was recommended to us, and by none other than the Royal Upholsterer, was to be found in prison—in prison, sir!—for theft. I could get no sight of any woman but the wife of the gardener, who was of no further service to me than shewing me the shops.”

The real parts are “He [will] not give me an honest measure” (the original being “He would not give me an honest measure”), “the woman who was recommended to us was to be found in prison” (I slipped in the clause about the Royal Upholsterer, because that’s who recommended the servant to the Herschels, in the middle and added the “—in prison, sir!—” for dramatic effect), and, “I could get no sight of a woman … shops”.

But even so, I’m writing fiction.

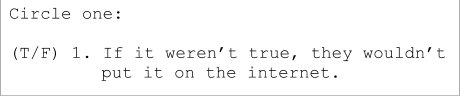

And it appalls me how many people believe fictional accounts and think that the details in them must be true. Perhaps the most obvious and egregious example I can think of is that a lot of folks blindly assume that the portrait Anthony Shaffer painted of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in “Amadeus” is an accurate one, when it is actually a slanderous misrepresentation. Likewise for Schaffer’s treatment of Antonio Salieri, by the way, who was certainly not a murderer, but that concept was actually stolen by Schaffer from Pushkin, so the blame does not rest with Schaffer alone.

Now, when a fiction writer does get details wrong, somebody out there will notice and call the author’s attention to the inaccuracy, like an old vicar writing to the Times correcting them on the placement of the wrong species of titmouse in Middlesex. But usually the reader will accept what was written as given.

There are certainly times when you can take a fictional portrayal’s accuracy to the bank: when Dick Stodghill wrote about working in a detective agency, when Robin Burcell writes a police procedural, and when Denise Hamilton writes about investigative reporting, they are informed by experience. Stodghill was once a Pinkerton man, Burcell was a SFPD detective, and Hamilton was a Los Angeles Times reporter. But the rest of the time, the writer’s imagination does the heavy lifting and there is only an appearance of verisimilitude. I’ve known some real private detectives, and my PIs owe much more to literary convention than they do to reality (Treviscoe included). Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express was famously inspired by the Lindbergh baby kidnapping and murder, but her diabolical mastermind Mr. Ratchett has nothing in common with the hapless Bruno Hauptmann (whose guilt is still a matter of great controversy). Hannibal Lecter is an altogether much more engaging person than Jeffrey Daumer was, and it would be a gross error to think that familiarity with the former provides any insight into the latter.

Even dramatic presentations of real events bear warning labels: “Inspired By A True Story” is just another way of saying, “Not A True Story Itself, Although We Borrowed Some Facts To Make It Convincing”.

So caveat emptor, Gentle Reader. I, for one, promise to you that I’m lying.

- Which I found in a marvelous book, Monsieur d’Éon is a Woman, by Gary Kates. [↩]

Hello Jim,

I am delighted. The way you are talking about your writing reminds me a lot of Orson Welles explaining his work, especially reading your concluding sentence.

Take care.

Uwe

Velma, alas, but Hannibal Lecter and Alan Treviscoe are not as real as you are. They are not 60-something male bloggers in drag.

Howdy, Uwe! I’m afraid I’m nowhere near as clever as Orson Welles, and I’m flattered by the comparison. For the rest of the CB audience, allow me to introduce Uwe Theel (“OO-vuh TALE”, for those of you who are wondering how it’s pronounced and don’t speak German), an old friend and father of the German 21-year-old I mentioned in my response to Steve’s post last Friday.