Monday, June 30: The Scribbler

BRAIN WAVES

by James Lincoln Warren

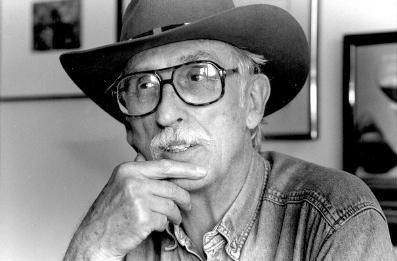

I was privileged to be personally acquainted with the late Dennis Lynds, who was perhaps the most important writer of detective fiction of his generation. Certainly he was one of the most important writers of short crime fiction. Den was the man who really introduced the concept of social commentary into private eye stories, something that is now regarded as an essential element of the genre. He did so because he wanted to make people think.

“If I have any overriding philosophy in my books, it’s that the ultimate function of literature is to disenchant the reader from the spell of received wisdom.”

Dennis thought that beliefs transmitted between generations were worthless if they were not constantly questioned and tested; as the above quote testifies, he felt it was his duty as a writer of fiction to challenge prejudice. Dennis believed he was battling stupidity and insensitivity, which of course he was, but he was also fighting neurological processing.

Huh?

A recent editorial in the New York Times, “Your Brain Lies to You” by Sam Wang, associate professor of molecular biology and neuroscience at Princeton, and Sandra Aamodt, former editor-in-chief of Nature Neuroscience, traces a lot of mistaken articles of faith to a neurological phenomenon known as source amnesia.

“The brain does not simply gather and stockpile information as a computer’s hard drive does. Facts are stored first in the hippocampus, a structure deep in the brain about the size and shape of a fat man’s curled pinkie finger. But the information does not rest there. Every time we recall it, our brain writes it down again, and during this re-storage, it is also reprocessed. In time, the fact is gradually transferred to the cerebral cortex and is separated from the context in which it was originally learned. For example, you know that the capital of California is Sacramento, but you probably don’t remember how you learned it.”

It turns out that as you do forget where you learned something, you are less prone to be critical of its veracity—you do not consider the source, as it were. This explains how “urban legends” gain acceptance, and of more sinister import, how deliberate propagandistic lies can become accepted by entire populations. The further back in time the lies are planted, the stronger their hold.

I’ve lost count of the number of times a preconception of mine was exploded by research. But as always, the scariest lies are ideas and not merely false facts. Because we all accept untruths as truths through the mechanism of source amnesia—as an example, in the Navy I sincerely believed that eating raw carrots as an after dinner snack would improve my night vision for the bridge watch I was to stand later in near complete darkness—we are usually unaware when we promulgate them further. Believing that carrots improve one’s vision is pretty benign. Believing that the white race has a manifest destiny to rule the world, a concept blithely accepted by Europeans and white Americans a century ago, is monstrous.

But problems with the brain eschewing critical functions don’t end there. When people concentrate on a specific task, they filter out perceptions that might normally engage their attention: consider this psychological test. This illustrates another phenomenon called inattention blindness. (It is not related to male floor blindness, where a male cannot see anything that has fallen on the floor, as that condition requires a Y chromosome—which by the way shows another example of source amnesia, because I don’t remember where I first heard that joke at all.)

Without spoiling the test results for the Gentle Reader, let me just say that this is a phenomenon that magicians have exploited for generations. And us mystery writers, too—how else do you hide clues? (If you answered, “Anybody who’s read Poe’s ‘The Purloined Letter’ knows the answer to that!”, then go to the head of the class.)

If you don’t object too strongly to a riff based on Clausewitz (“Der Krieg ist eine bloße Fortsetzung der Politik mit anderen Mitteln”1), a lot of authors consider fiction as the extension of the truth by other means—by which they mean that they deal with general truths rather than specific ones, with psychological and emotional truths, even though their characters and their predicaments never existed outside the imagination. Even those general truths, assumed as they are, can easily inadvertently fall into Dennis’s despised “spell of received wisdom”. The suspension of disbelief so important to fiction can even be dangerous, if it is not confined to the mere surface of the story—the reader must question the author, too, and determine if there’s an agenda.

If you don’t object too strongly to a riff based on Clausewitz (“Der Krieg ist eine bloße Fortsetzung der Politik mit anderen Mitteln”1), a lot of authors consider fiction as the extension of the truth by other means—by which they mean that they deal with general truths rather than specific ones, with psychological and emotional truths, even though their characters and their predicaments never existed outside the imagination. Even those general truths, assumed as they are, can easily inadvertently fall into Dennis’s despised “spell of received wisdom”. The suspension of disbelief so important to fiction can even be dangerous, if it is not confined to the mere surface of the story—the reader must question the author, too, and determine if there’s an agenda.

Personally, I think Dennis was right on the money. That there are neurological predispositions to embracing falsehood only makes it the more critical that we scribblers get our facts right. All the facts, ma’am.

- “War is a continuation of politics by other means.” [↩]

Oh, I’m envious! I’ve had inattention blindness on my article to-do list because it appealed to the geek in me. I hadn’t related it to lying, though.

I wonder if American generations are as good (or bad) as handing down information as they might have been a century or more ago? On the one hand, it seems to account for the ‘wisdom from the mouths of babes’ who don’t have the burden of ingrained preconceptions. On the other, it seems recent generations have to relearn the lessons of their parents– even presidents seem to be guilty of ignoring the wisdom of their fathers.

A thought-provoking article, James.

Yes, good column, and like James, I have a piece in mind that it overlaps with. Fortunately the are quites different, because mine isn’t as well researched.

I could rewrite that, but I won’t.

The late great Daniel Patrick Moynihan said “everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but not their own facts.” What a nice idea…

Somehow, someway I’m going to work the word Hippocampus into a conversation this week.

“Hippocampus” is also Latin for “seahorse”, if that’s any help.

>Somehow, someway I’m going to work the word Hippocampus into a conversation this week.

For once LOL actually means something. Travis, don’t look now, but I think you just used the word.

Meanwhile, the giraffes, rhinos, and me… We’re heading back to the Hippo campus to meet the video gorilla.

I really loved your piece, Jim, and Den would’ve, too. Thanks for taking Den’s insight to the next step — we have a predisposition for idiocy, which sure does explain a lot! BTW, I’m a huge fan of CriminalBrief.com. All of you guys are great writers & thinkers! best, Gayle Lynds

Coming from you, Gayle, that means a lot—thanks for the kind words. I agree wholeheartedly with your assessment of my six fabulous colleagues.

Great column. I wish I’d written it.

Are you telling me that eating carrots won’t improve my night vision?!?

I guess as a magician, I’ve trained my perception to observe little things that most people miss. So I passed the test. But it was difficult counting passes while laughing.

By the way, my introduction to Dennis Lynds is possibly an example of inattention blindness. I encountered him as a child (me, not him) when I read The Mystery of the Moaning Cave, a “Three Investigators” novel that Den wrote under the name William Arden. I finally had him sign it a couple years ago (Las Vegas Bouchercon?)