Monday, July 12: The Scribbler

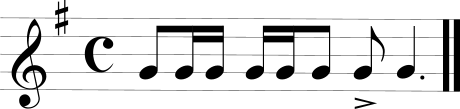

RUM-TITTY-TITTY-TUM-TAH-TEE

by James Lincoln Warren

It has happened to every one of us. It’s one of those common experiences that unites all of humanity in universal experience. It probably has some deep neurological foundation, and might provide profound insight into the very nature of consciousness.

If only it weren’t so damn irritating.

I’m referring to having something stuck in your inner ear.

You know what I’m saying: a tune gets lodged in your brain and no matter what you do, you can’t get rid of it. Evil people plant such tunes in people’s minds deliberately, by whistling or humming something at us, say a particularly irritating advertising ditty, and then we the victims are stuck with it. So to avoid any enmity from the Gentle Reader, I’m not going to cite any examples except the one that provided the above title, from the eponymous 1958 comic horror short story by my hero, Fritz Leiber.

In the story, the ditty threatens to take over the Earth as the population of the entire world stops everything—except succumbing to the seductive rhythm of the musical expression. In the story, this turns out to have been planned by a long dead witch doctor as a way to seize global dominion, a shaman now reaching from beyond the grave in his demonic lust for conquest.

It has been suggested by webster Henry Lowengard that Leiber based his story on an actual incident that occurred in New York in 1913, an account of which he has published on two different websites (here and here). I do not know if Lowengard’s claim is true or not—Chicago and Los Angeles (and later, San Francisco) were Leiber’s chief locales, and they’re the ones that inform his fiction. Lankhmar in particular is an amalgam of Chicago and Los Angeles, by his own admission. On the other hand, Leiber did live in New Jersey for a year in the very early 1930s, and Lowengard’s urban legend is of precisely the sort that would have fascinated Fritz.

Not that it makes too much difference, because it’s one of those ubiquitous behavioral phenomena that cross all cultural boundaries. It is the Holy Grail of every advertising executive and political propagandist who ever lived to imprint some idea so firmly in someone’s head that they are reminded of it wherever they go and whatever they do. This is exactly what they have in mind. (It’s not a mistake that Leiber’s unseen villain, like the Mad Men and propagandists, is trying to dominate the world.)

And, in a more personal sense at least, of every performer. And of “characters” (as in, “That Leigh Lundin is a real character”). That’s why songs have hooks and Veronica Lake had only one eye.

And of every writer. That’s where lines and catchphrases come from, pilgrim. Say hello to my little friend.

I frequently say that a fiction writer’s only real job is to entertain, to not waste the Gentle Reader’s time during the span that the reader becomes engaged in the story. But what every writer really wants is for his readers to remember the work and to think about it afterward, for the story to have achieved something permanent. And nothing does that like the sort of meme1 that Leiber was having so much fun with.

But on the other hand, there’s the danger of overexposure and self-parody. Poor Bulwer-Lytton had no idea of the tsuris that the famous first sentence of Paul Clifford would leave in its wake. Some people I know refuse to buy the products immortalized by musical commercials on the grounds that the composer of the unforgettable ditty deserves to be drawn and quartered for causing irreparable psychic damage. Some ditties are so virulent that they are excised entire from the collective consciousness. Try to remember one of them and there’s nothing there but vacuum. Usually, I think they are displaced by something else.

So it’s not enough to memorable. You also have to be benign.

Which is how Leiber ended his story, by invoking a benign replacement for the devouring rhythm. The shade of the witch doctor is forced, presumably on the orders of the Prince of Darkness himself, to produce an antidote. A medium receives a message from him to pass on to his great-times-seven grandson: “Dear Descendant, They made me stop it. It was beginning to catch on down here.”

Tah-titty-titty-tee-toe!

- Unlike Steve Steinbock, I regard Dawkins’ theory as quite tenable, and I disagree that it is unverifiable or immeasurable in a scientific sense—but science aside, it also stands its ground in critical analysis, since it’s a concept very easy to grasp and instantly recognizable. Which is not to say that I don’t respect Steve’s opinion on the issue or that his objections to it are without merit; only that we approach it in different ways. [↩]

by Bob Byrne

by Bob Byrne

Bob drew my attention to the Praed Street Irregulars headed by the Honourable George Vanderburgh. A physician and retired army major, he founded a small press specializing in Edwardian and Victorian fiction. George is working on a nascent

Bob drew my attention to the Praed Street Irregulars headed by the Honourable George Vanderburgh. A physician and retired army major, he founded a small press specializing in Edwardian and Victorian fiction. George is working on a nascent