Friday, August 8: Bandersnatches

MAPPING FICTION

by Steve Steinbock

Last month fellow Criminal Briefer John Floyd shared some thoughts on plotting in a Mississippi Mud column, “Map Quest.” I enjoy that topic, and I enjoyed John’s column. In fact, it generated a lot of behind-the-scenes discussion among us CD columnists as James Lincoln Warren explored nodal structure maps of each of our websites.

I realize that plotting (which sounds a lot like plodding) had been out of fashion for the last several decades, but I enjoy it, if for nothing else, as a thought exercise. Studying plotting—the architecture of fiction—can help authors create more satisfying stories and provide readers with a better appreciation of them. As John’s column suggested, plotting—however loosely defined—can also help keep a story from derailing.

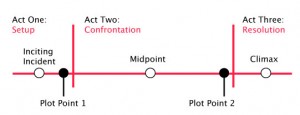

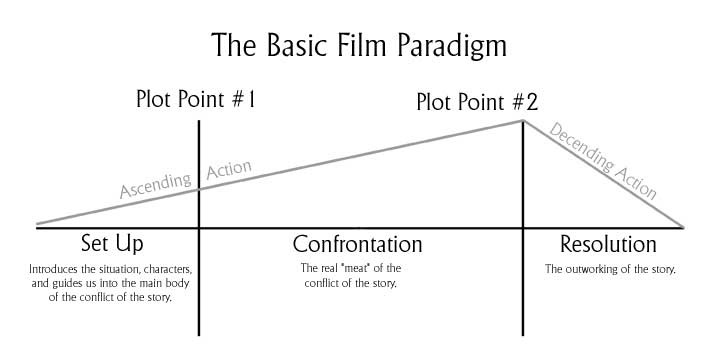

Some of the best work in the area of plotting has come from scriptwriting guru Syd Field. In brief, Field articulates a three-act structure with strategically placed plot-points at which the story pivots, reverses, or otherwise surprises.

Field’s system works for just about any fictional medium, but is particularly tailored (down to the page numbers) to full-length screenplays. It sounds formulaic, and it is. But as I said, it works. Pick up your favorite novel or movie and see for yourself. Field didn’t invent this system. He merely articulated it. I’m certain he would admit that it’s a structure that has been inherent in storytelling for centuries.

Inherent is the operative word. I predict that writers who focus too much on the structure and not enough on the storytelling will create dull fiction. On the other hand, I reckon that most successful writers, without ever having read Syd Field, intuitively pace their stories so that Field’s paradigm accurately represents their plotting.

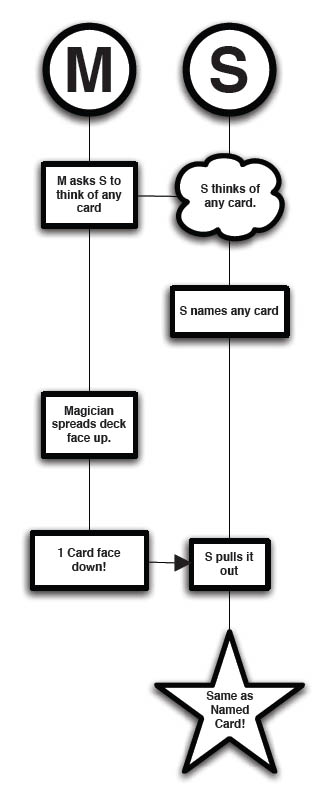

I was recently sent a short ebook on the subject of mapping magic routines, created by magician Alvo Stockman. Stockman uses a very simple set of flowcharting shapes to graph the steps, events, and surprises in a magic routine. He uses circles to represent people, squares to represent states of events, arrows to indicate objects being handed from one person to another, thought-bubbles serve to show thoughts, and stars denote climaxes.

Here’s an example showing the plot of a basic “pick-a-card” trick:

Some of the advantages, as Stockman points out on his website and in his ebook, are that it helps a magician optimize the effect, improve interaction, and illustrate the ratio of steps to climaxes (getting the most bang from a buck).

I’m sure someone, somewhere, has developed a flowchart language for mystery plots. If so, such a system would include ways of diagramming real and perceived situations, backstories, plot-twists, revelations, and red herrings, among other elements.

Please let me know what you use, or what you would use if it was available. I’ll see you all in seven.

Nice piece Steve.

I would love to see a flowchart for mystery plots, if such a generic thing were possible.

I’m in love with plotting. I like to get a robust structure and set of characters in place before I begin the writing of a story. The trick after that, I think, is to remember it’s just the starting point – anything can happen or change during the actual writing.

I read recently J.G.Ballard is quite fanatical about plotting.

Apparently, the outline for one of his novels was longer than its resulting book.

Great column, Steve. I agree that most good stories follow Syd Field’s three-act “formula” whether their authors were previously aware of the system or not.

Other great references on this subject are STORY, by screenwriting instuctor Robert McKee, and THE WRITER’S JOURNEY, by Christopher Vogler. Vogler’s book, based on the work of Joseph Campbell, is an updated discussion of mythic structure (“The Hero’s Journey”) in fiction, and closely parallels Field’s system. I’m paraphrasing here, but editor Elizabeth Lyon said that a knowledge of this kind of plotting technique is a fiction writer’s equivalent of the musician’s memorization of scales.