Monday, September 15: The Scribbler

THE DIOSCURI DIAGRAM

Considering the Storyline Diagram, Part the Second

by James Lincoln Warren

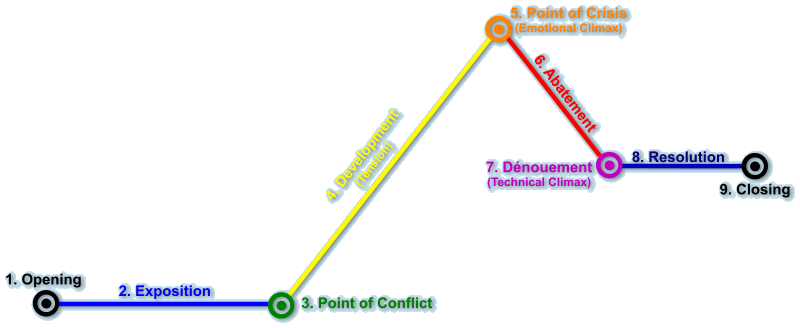

Last week, I offered my version of the venerable storyline diagram, seen above, as a cure for three-act-itis. One of its advantages, I claimed, was that it was more flexible than the vaunted three act structure. This week I aims to back up that claim by diagramming a couple of my stories by way of illustration.

The basic diagram has nine elements. Not all of them are essential—al- though some are—and some can be combined, so a story doesn’t necessarily have to have all nine elements to work well.

The basic diagram has nine elements. Not all of them are essential—al- though some are—and some can be combined, so a story doesn’t necessarily have to have all nine elements to work well.

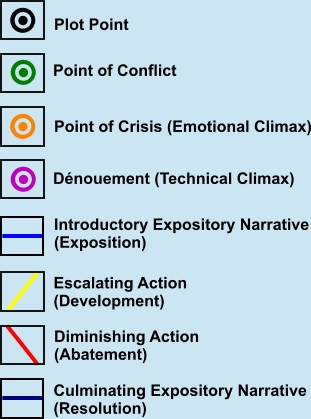

These elements fall into two basic categories: (1) plot points, and (2) narrative streams. The key at left shows plot points as circles and narrative streams as lines. A plot point represents a singular moment in the story where the direction of the action changes. Plot points are connected by narrative streams.

Although there are no fixed number of points or streams in any given story, some of them are specialized, so I’ve color coded them. In the key, I’ve also added a brief description of each one.

Got all that? Fabuloso.

Now I’m going to ask you to read “The Dioscuri Deception”1 This is the first story I sold to Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine and introduced my series detective, Alan Treviscoe. It was featured in the March 1998 issue.

I chose it because it has the most standard structure of all my stories. It was strictly modeled on Arthur Conan Doyle, where Holmes and Watson are sitting at home when an unexpected and unusual client calls who then relates a curious tale. Our heroes get drawn into the adventure, and after some excitement, Holmes apprehends the criminal. The story closes with the Great Detective patiently explaining how he solved the mystery to the admiring Watson and the thick Lestrade. Only instead of 221B Baker Street, I used New Lloyd’s of London in Pope’s-Head Alley.

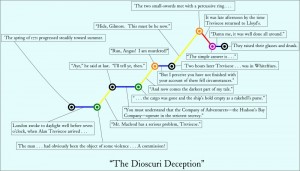

All done? Excellent. I hope you enjoyed the story, he said with manly modesty, but the reason I asked you to read it is to compare it with the diagram at right. I’ve identified each of the plot points and narrative streams with a quote from the story.

All done? Excellent. I hope you enjoyed the story, he said with manly modesty, but the reason I asked you to read it is to compare it with the diagram at right. I’ve identified each of the plot points and narrative streams with a quote from the story.

As you can see, its shape more or less conforms to the original template. The major difference is that instead of loading all the exposition up front before the point of crisis, it has been doled out between sequences of escalating tension.

I did not draw the diagram of this story before I wrote it. I never do. But the plot points were all decided in advance with the basic diagram in mind. Of course this story’s diagram differs from the template somewhat—all stories do, but with mystery stories, that’s built in. One thing that makes traditional detective stories different from non-mystery stories is the presence of two essential conflicts: the first involves the commission of the crime, and the second involves the solution of the crime. Of these, the second is the more important. In my diagram, there are two points of crisis corresponding to these two conflicts. The first is the murder of Captain Nichols, and the second is the small-sword duel between Treviscoe and Mr. Eccles.

The dénouement, however, is when Treviscoe explains his solution to the crime, the “I’m-sure-you’re-all-wondering-why-I-asked-you-here-tonight” moment that is a formulaic feature in traditional detective stories.

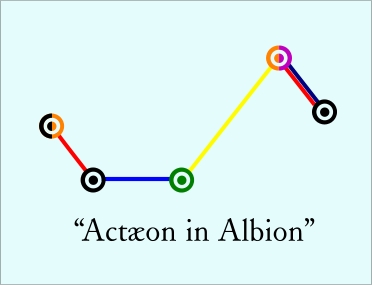

Although they are separate moments in “The Dioscuri Deception”, the point of crisis and dénouement can be and frequently are combined. In my story “Actæon in Albion”, for example, Treviscoe confronts the villain with his deductions and winds up getting shot in the resulting scuffle. “Actæon in Albion” is also worthy of mention (structure-wise, that is) in that it begins not with exposition, but with a bizarre murder in progress (a country squire is mauled to death by his own hunting dogs), which in the course of events must needs be investigated. Starting at a moment of crisis is a common narrative technique for drawing in the reader. In screenwrit- ing, this is called a “teaser” and is a stock ingredient of hour-long TV dramas. Anyway, the “Actæon in Albion” diagram looks like this:

You will notice that the opening is fused with a crisis point, and that the emotional climax and dénouement plot points have also been combined, as have the abatement and resolution narrative streams.

Probably my most complex story in terms of structure is “Black Spartacus”. It is told as a series of flashbacks during a murder trial. I constructed it that way to make transitions between plot points shorter,2 because the reader forgives abrupt changes in a succession discrete memories that they would never tolerate in a straight sequential narrative. As a consequence, each one of the flashbacks has its own micro-storyline, so the macro-storyline diagram is quite involved, although the tension is higher in each succeeding episode. To me, the most interesting thing about it is that the emotional climax actually occurs after the dénouement. 3

By now the Gentle Reader can certainly see why I think the storyline diagram is more flexible and useful than three-act structure. None of this answers the question of whether diagramming or outlining are necessary to crafting good fiction, however. Last week, Melodie commented, “Anything that has to be diagrammed is not writing. It’s busy work.”

Well, I’m not sure I agree completely, but she has an excellent point. Any time spent not writing is time spent doing something else, even if you’re doing something fundamental to telling the story, like reading or research. But I do think that structure is very important, and diagramming is really nothing but a form of outlining, which certainly has its champions among the mystery literati. One of the things that makes fiction fiction, that differentiates the economical world of story from the tumultuous world of reality, is the imposition of structure—and stricture—in the telling of the tale. 4

So the actual question to be answered is not, “Is this writing?”, but, “Will this assist me in telling a story?”

The answer is yes if diagramming improves the self-discipline required to string words into a story, or if it kickstarts your imagination by causing you to contemplate how to tell the story in the best possible way. It can be helpful if you want to see exactly how or why a story does or doesn’t succeed. Otherwise, leave the diagrammer in the toolbox. But either way, give that three-act thingy to the Good Will or the Salvation Army or other charity that accepts second-hand goods. (Be sure to ask for a receipt.)

And now we return to our regularly scheduled web log.

- Write to me using the “Contact” link in the “Admin” box at left to have me send you a copy. [↩]

- For very practical purposes: the story had to be under 14,000 words or face certain rejection for being too long. The first draft (without the flashbacks) was over 15,000 words, so the story required cosmetic surgery. [↩]

- SPOILER: The dénouement is a “Perry Mason moment” in the trial, but the point of crisis occurs when Treviscoe is mugged on his way home from the courthouse. [↩]

- As Oscar Wilde had it, “The good ended happily, and the bad unhappily. That is what fiction means.” Or, as I once advised a young writer, “Remember that fiction has more rules than real life.” [↩]

>And now we return to our regularly scheduled web log.

Awwwww…

By the way, today is Agatha Christie’s birthday. What a dame!

JLW.

I enjoyed this column. I printed out the story and now will read and compare.

Thanks for the guidance.

Terrie