Monday, November 5: The Scribbler

WANDERINGS OF A WORD

by James Lincoln Warren

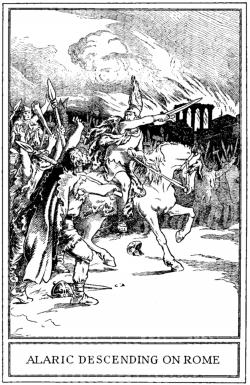

On August 24, 410 CE, a Roman-trained and Arian1 Christian general invaded the city of Rome and occupied it for three days. A few public buildings were burned, but the churches were all spared. There was no wholesale looting and not a single report of a Roman woman being raped. Several denizens of the city were enslaved, but subsequently allowed to purchase their freedom at below market prices. The only prisoners the invaders retained were political hostages. It is worth noting that the general had laid siege to the city twice before to demand that his people be given land, payment promised to them for their previously faithful service to the Empire as foreign soldiers. On the occasion of the previous sieges, the general had withdrawn from the city after receiving ransom and Rome’s promise to fulfill their contractual obligations. This time, however, he did not receive any offers, and for the first time in eight hundred years, Rome was occupied by an enemy.

On August 24, 410 CE, a Roman-trained and Arian1 Christian general invaded the city of Rome and occupied it for three days. A few public buildings were burned, but the churches were all spared. There was no wholesale looting and not a single report of a Roman woman being raped. Several denizens of the city were enslaved, but subsequently allowed to purchase their freedom at below market prices. The only prisoners the invaders retained were political hostages. It is worth noting that the general had laid siege to the city twice before to demand that his people be given land, payment promised to them for their previously faithful service to the Empire as foreign soldiers. On the occasion of the previous sieges, the general had withdrawn from the city after receiving ransom and Rome’s promise to fulfill their contractual obligations. This time, however, he did not receive any offers, and for the first time in eight hundred years, Rome was occupied by an enemy.

As far as invasions go, it was pretty tame. The invaders were disciplined troops who avoided unnecessary violence. It was certainly nothing like the two days of murder and drunken rapine visited by Wellington’s troops upon Badajoz, Spain, in 1812. But the Roman-trained general was Alaric, and his army were Goths, a Germanic tribe. Although his contemporaries never referred to Alaric as a barbarian, this is the date usually associated with the Fall of Rome and the beginning of the Dark Ages. The word Goth was adopted as a synonym for wanton destruction. The same thing happened to the word Vandal, designating another Germanic tribe, after they sacked Rome some thirty-five years later.

The Visigoths, i.e., the Western branch of the tribe headed by Alaric, eventually found a permanent home in Spain, after having been expelled from France by, you guessed it, the Franks, another Germanic tribe that would presently produce Charlemagne. The Spanish Goths adopted Roman Catholicism in the 8th century, at about the same time as the Moors invaded the Iberian Peninsula. They maintained their independence only in the mountainous north for centuries. Thereafter, history refers to them as the Spaniards. Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, a.k.a. El Cid, the 11th-century national hero of Spain, was of solid Gothic stock.

The Visigoths, i.e., the Western branch of the tribe headed by Alaric, eventually found a permanent home in Spain, after having been expelled from France by, you guessed it, the Franks, another Germanic tribe that would presently produce Charlemagne. The Spanish Goths adopted Roman Catholicism in the 8th century, at about the same time as the Moors invaded the Iberian Peninsula. They maintained their independence only in the mountainous north for centuries. Thereafter, history refers to them as the Spaniards. Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, a.k.a. El Cid, the 11th-century national hero of Spain, was of solid Gothic stock.

The term “Gothic” fell pretty much out of use until the mid-17th century, when it was revived to describe the architecture of medieval cathedrals (which was invented by the French), especially with regard to their characteristic pointed arches. In the 1600s, Europe was in a veritable frenzy of neo-classical baroque architecture, and calling the medieval churches Gothic was meant to suggest that these sublime masterpieces of faith, art, and engineering were somehow barbaric. The term was also applied to medieval blackletter scripts (which are also sometimes equally inappropriately referred to as “Old English” for some reason).

The term “Gothic” fell pretty much out of use until the mid-17th century, when it was revived to describe the architecture of medieval cathedrals (which was invented by the French), especially with regard to their characteristic pointed arches. In the 1600s, Europe was in a veritable frenzy of neo-classical baroque architecture, and calling the medieval churches Gothic was meant to suggest that these sublime masterpieces of faith, art, and engineering were somehow barbaric. The term was also applied to medieval blackletter scripts (which are also sometimes equally inappropriately referred to as “Old English” for some reason).

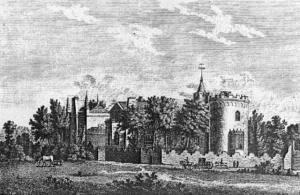

A hundred years later, the insult intended by the term had been blunted by use, and the term was simply perceived as a word that applied to a particular style. The middle ages were no longer viewed with nothing but contempt. Although the Palladian architectural style still ruled the roost, there were glimmerings of renewed interest in the age of chivalry and its attendant romance. Remember Horace Walpole, the man who coined the word serendipity? In 1748, he purchased an estate called Strawberry Hill, north of London, and proceeded to build a folly to call his home, a “little Gothick castle”. The Gothic Revival was born, culminating in the magnificent Palace of Westminster, better known as the British Houses of Parliament, in 1849.

A hundred years later, the insult intended by the term had been blunted by use, and the term was simply perceived as a word that applied to a particular style. The middle ages were no longer viewed with nothing but contempt. Although the Palladian architectural style still ruled the roost, there were glimmerings of renewed interest in the age of chivalry and its attendant romance. Remember Horace Walpole, the man who coined the word serendipity? In 1748, he purchased an estate called Strawberry Hill, north of London, and proceeded to build a folly to call his home, a “little Gothick castle”. The Gothic Revival was born, culminating in the magnificent Palace of Westminster, better known as the British Houses of Parliament, in 1849.

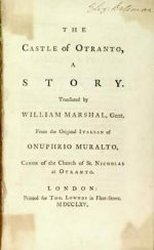

Walpole’s interest in medievalism did not end with architecture, however. He was in love with terror and superstition, and saw medieval times as the perfect expression of everything grim and spooky. In 1764, Walpole wrote The Castle of Otranto, telling of a supernatural revenge against a cruel Italian noble. Although it’s not a very good book, it was a big hit, and the Gothic novel had been born.

Walpole’s interest in medievalism did not end with architecture, however. He was in love with terror and superstition, and saw medieval times as the perfect expression of everything grim and spooky. In 1764, Walpole wrote The Castle of Otranto, telling of a supernatural revenge against a cruel Italian noble. Although it’s not a very good book, it was a big hit, and the Gothic novel had been born.

Hordes of Gothic novels appeared within the next sixty years. The Monk by Mathew Lewis. The Castle of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe. Melmoth the Wanderer by Charles Robert Maturin. Jane Austen even wrote a parody of the Gothic novel, Northanger Abbey. By the end of the 18th century, Gothic short stories were even being written in America. Most of these were not so medieval in spirit as they were Jacobean revenge dramas cast in novel form, characterized by depravity, torture, and gore — but the Jacobean revenge dramas had also uniformly been set in medieval times.

In the early 19th century, Elizabeth Gaskell in England and Edgar Allan Poe in America achieved commercial success with Gothic short tales. Much of Poe’s fiction can be described as Gothic, especially “The Fall of the House of Usher”, featuring as it does a suffering beauty, a brooding and stifling morbidity, and a terrifying old house.

But the peregrinations of the word were not over.

In 1848, Charlotte Brontë gave us Jane Eyre. Now, Jane Eyre is not, in the strictest sense, a Gothic novel. Be that as it may, Brontë was smart and skilled enough to infuse her story with Gothic elements as a means to explore the nature of morality. But in place of Lewis’s twisted Ambrosio or Radcliffe’s sadistic Count Montoni, Brontë gives us the Byronic Mr. Rochester, the romantic lead. Daphne du Maurier, herself an MWA Grand Master, famously repeated the formula in Rebecca in 1938. The 20th century Gothic Romance was born. Scores of paperback potboilers with cover art featuring a beautiful girl running beneath a stormy sky gazing with fear at a gloomy mansion over her shoulder verily peppered wire book racks in drugstores in every corner of the USA during the 40s, 50s, and 60s. The subgenre survives to this day — there is even a Gothic Romance chapter of the Romance Writers of America — but its once ubiquitous popularity has declined.

The most recent avatar is the post-punk urban2 exhibitionist Goth of contemporary subculture, replete with fetishes, death rock, and black lipstick. These paragons of charm and virtue originated in England in the 1980s and for some incomprehensible reason are still with us today. I suspect they adopted their nomenclature from their unholy attachment to blackletter script, always popular among social outcasts, because I can’t believe any of them actually read classic English literature. Their understanding of what it means to be Gothic cleaves closer to Charles Addams than to Chieftain Alaric. Contemporary Goths revel with abandon in their decadence. I can’t help but wonder what Alaric and his people, who were blondes and eschewed such effeminate trappings as cosmetics and who fiercely battled against a decadent civilization for the sake of their own future, would have thought of them. They probably would have been direly insulted. Spanish Goths of the sixteenth century would surely have sent such creatures to face the gentle ministrations of the Inquisition. The gloomy mansion on a Mary Stewart novel would have been looking over its shoulder in fear at the girl. (There’s a good short story in there somewhere which I will never write.)

I suspect they adopted their nomenclature from their unholy attachment to blackletter script, always popular among social outcasts, because I can’t believe any of them actually read classic English literature. Their understanding of what it means to be Gothic cleaves closer to Charles Addams than to Chieftain Alaric. Contemporary Goths revel with abandon in their decadence. I can’t help but wonder what Alaric and his people, who were blondes and eschewed such effeminate trappings as cosmetics and who fiercely battled against a decadent civilization for the sake of their own future, would have thought of them. They probably would have been direly insulted. Spanish Goths of the sixteenth century would surely have sent such creatures to face the gentle ministrations of the Inquisition. The gloomy mansion on a Mary Stewart novel would have been looking over its shoulder in fear at the girl. (There’s a good short story in there somewhere which I will never write.)

Humpty-Dumpty told Alice that when he used a word, it meant what he wanted it to mean. “Gothic” has meant so many things to so many people that you would think it’s been diluted to the point of losing all meaning, but it hasn’t. There’s a magic to it that refuses to die.

I have a feeling it’s still on the move.

- Arian Christians believed that Christ was created by God the Father, a doctrine in violation of the Nicene Creed: belief in the Trinity assumes that its three aspects are co-eternal, that the Son and Holy Ghost are emanations of God rather than finite creations. The sect’s leader, Arius, was a contemporary of the Nicaean Council, which declared his tenets heretical. Nevertheless, Arius had powerful allies among the Imperial aristocracy and was expected to be rehabilitated by the orthodox bishops when he unexpectedly died, leaving the Trinitarians a clear field. [↩]

- You might think that the Gotham City of comicdom’s Dark Knight, the Batman, is etymologically related to the Goths, as I did, but you’d be wrong. “Gotham” is one of the nicknames of New York City, dating from the 1850s, and comes from a proverbial town known for the folly of its elders, the “wise men of Gotham”. Batman’s atmospherically Gothic appurtenances were invented in the 1970s by writer Denny O’Neil and artist Neal Adams and then taken downtown by Frank Miller in the 80s. The original “Bat-Man”, created by Bob Kane in 1939, was really nothing more than a cowled version of Dick Tracy, especially with regard to the weird villains, and lived in Gotham City by way of analogy to Superman’s environs of “Metropolis”, another nickname for the Big Apple. [↩]

This comment conveys no real information – I just want to say, “A fantastic piece, thank you.”

Another way to think about todays Goths is that they are just the latest wing of the blackclad artsy non-conformists who go back to, at least, the Beatniks.

Mike Davis has written a book criticising modern empires (guess who) and the wonderful title is In Praise of Barbarians.

>Hordes of Gothic novels…

Clever!

I read Batman in the ’60’s and ’70’s and knew about the NYC origins of Gotham City but I never thought how fitting the “Gothic” connection is to the city of the Dark Knight of the later comics, uh, I mean “graphic novels.” (Holy Serindipity!)