Monday, June 4: The Scribbler

LINGUICIDE

by James Lincoln Warren

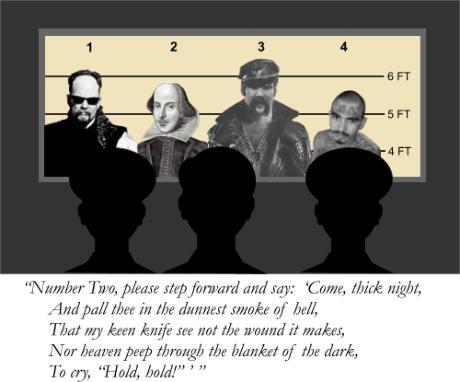

Steve has already spilled the fact that I’m a diction cop—I guess it didn’t occur to him that I might be deep undercover, and that by revealing my law enforcement status, he might endanger my life and the safety of the community. Which is just as well, because I’m not undercover, believing that a visible law enforcement presence in the neighborhood is an effective deterrent against crime.

Leigh has just made some comments and recommendations concerning style. Well, gird your loins for more—although it strikes me that reading a wordsmith’s ideas about language is probably about as interesting as reading what an painter has to say about paint. Major yawn. But I digress.

Diction cops have to enforce many laws—the laws of punctuation, the laws of grammar, the laws of usage, style, and so on. Most responsible citizens understand that the laws are there for their own comprehension. Usually, lawbreakers violate the letter of the law out of ignorance or by accident, and more frequently these days, out of negligence. Then again, some are scofflaws who disobey the laws when they think nobody’s looking. Usually, it is sufficient to let folks off with just a warning—“I hope you’ve learned your lesson, sir, and will avoid comma splices from now on.”

Then again, there are what you might call the Red Light Districts of language, where otherwise unlawful behavior is tolerated, or even encouraged. I recall a wonderful anecdote by the inimitable Gary Phillips concerning an editor who had been just hired after winning her hard-earned B.A. in English from Sarah Lawrence. She was assigned to line edit one of Gary’s books, and took the opportunity to correct the grammar used by Gary’s homeboy gangsta characters. Dost thou knowest that of which I speaketh?

But the worst of all possible crimes is First Degree Linguicide—the deliberate murder of language. A crime most rare, since most instances of linguicide are in the Second Degree, i.e., not commited with malice aforethought, but becoming more common. Every time someone whines, “Well, you knew what I meant,” it is at least an indication of criminal negligence on their part.

I have often been pilloried as being a linguistic conservative who refuses to acknowledge that language is continuously evolving. Nothing could be further from the truth. I am all in favor of the language getting richer. What I deplore is when the language shrinks and becomes trivialized. For example: you can’t use the word “awesome” to express that which inspires awe any more, because “awesome” has been watered down to such an extent that its use invariably invokes the image of some idiot adolescent expressing mindless approbation in concord with some present trend or fashion. That is a long and grievous fall for such a noble concept.

On the other hand, new words seemed called for by new phenomena. (Although one should be very careful about portmanteau words, which are usually ugly and etymologically inaccurate, like “homophobia”—please note that I am not taking a political stance by disapproving of the word, which I do on strictly aesthetic grounds. I categorically abhor the condition it describes.) I don’t have any problem with “cyberspace” (coined in 1982) or “blog” (from 1999), because they fill lacunae.

I think this is more important in short fiction than anywhere else, because short fiction requires economy of expression. This means that using the mot juste in place of a drawn out description is a skill of the trade—and when the mot juste becomes so weakened that it loses its piquancy, that’s one less trick in the magic bag for us verbal legerdemainists. Take “obsession”. It formerly described a state of literal possession—you were obsessed by something—something that had an eldritch control over you, something so powerful that it sapped your very will with a vampiric inexorability. Now it means nothing more than an irritating fixation, so much so that it has switched from appending from the object to being an action on the part of the subject: “Jack’s obsessing on chocolate.”

Or how about “enormity”, referring to a criminal and unnatural act so repulsive to be of virtually inconceivable scale, but is used these days with casual indifference as a synonym for “big”? Likewise, “infamous” is now used as an amplification of “famous”, instead of meaning “of evil reputation”. The Holocaust had enormity, but not the Spruce Goose, which was merely huge. Adolf Hitler is infamous, but not Brad Pitt, who is merely ubiquitous.

Alas! “And the king was much moved, and went up to the chamber over the gate, and wept: and as he went, thus he said, O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! would God I had died for thee, O Absalom, my son, my son!”

So if Diction City has Diction Police, are there private dicts?

And hard-boiled dicts?

Does the police force include Dict Tracy or Dict Barton?

Instead of K-9, is there a K-12 unit?

Would malinguists seek legal representation in the Public Offenders office?

For verbicide, would a judge pronouns a mandatory sentence?

What is the price of PUNishment?

Yes, but they are not supported by public syntax dollars; yes, who deal with the grammar side of life; both, and they report to Detective Superintendant Lex Icon; the K-12 unit is responsible for teaching suspects a lesson; if lawbreakers can’t afford their own counsel then one will be full pointed; the judge should impose a periodic sentence; and penalties for such dirty acts should always soot the grime.

A certain Diction Bobbie/Booby criticized Winston Churchill (a very fine writer) for ending a sentence with a preposition. Churchill’s tongue-in-cheek Teutonic reply: “Ending a sentence with a preposition is something up with which I will not put!” (Or so the story goes…)

Have you ever read Rex Stout’s GAMBIT? That’s the novel that begins with Nero Wolfe burning the Webster’s Third International Dictionary in his fireplace because it is descriptive rather than prescriptive (i.e. it tells how words are actually used, not how they SHOULD be used). I wrote an essay in TAD, of blessed memory, arguing that the whole plot of that novel was an argument against the dictionary. Stout, by the way, soaked his own copy of the dictionary in gasoline and used it to burn wasp’s nests.

There are some myths concerning crimes that are not really crimes. There is nothing wrong with ending a sentence with a preposition. Splitting infinitives is also perfectly allowable. As an example of evolution, I also think that use of the accusative pronoun as the object of a copula (“It’s me” or “It’s him”) has so completely routed the “more correct” nominative pronoun (“It is I” or “It’s he”), that there is little point in considering the former incorrect anymore.

Webster’s 3rd International created a furor not because it was descriptive–even the OED is descriptive–but because it made no distinction between slang and more formal English, which does a disservice to the reader looking to improve the tone of his English. I think that as American dictionaries go, it’s a very scholarly dictionary, and that it generally fulfilled its purpose, which was to present a survey of American usage. Noah Webster would have hated it, but he was a rather unpleasant chap to begin with.

The beauty of the OED is that it lists usages in historical order instead of leading with the most frequent usage, making it easy to trace the evolution or corruption of a word.

The OED also has a peculiar criminal connection. In the early years, one of its more productive contributors was a sex-addict and murderer, one W.C. Minor, who labored for the OED within the confines of the Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane.

Tom and Rob, great stories. Jim, thank you for putting to bed the myths of split infinitives and ending with prepositions.

There isn’t much that annoys me about improper speech. The overuse of “like” and “you know” is tedious. But my pet peeve is the double copula, “is is.” I’ve never seen it appear in print, but I hear this crime committed regularly, even by well-educated people who would never misuse “like” or “you know.”

An example of the double copula would be something like: “the thing of it is, is that. . .”

It’s like fingernails on the now proverbial chalkboard.