Monday, January 19: The Scribbler

LIFE SENTENCE

by James Lincoln Warren

Some months ago I wote a column about logic, one of the components of the classical educational curriculum called the Trivium. The other two components were grammar and rehetoric. I promised I’d get back to the other two at a later date, and now I’m fulfilling one half of that pledge.

Grammar, baby. For our purposes, grammar can be described as the study of the relational structures and elements employed for meaningfully arranging words in sentences. (This is my own description and I do not offer it as definitive, because grammar is really a lot more complicated and whole volumes have been written on the subject.)

Several years ago, I participated in a lively on-line discussion on the questions, Do writers have to have a strict knowledge of the rules of English grammar? Or is it good enough merely to get your point across, the rules be damned? Or some variant thereof. The subject had been brought up by someone who felt that insistence on “good grammar”, i.e., proscriptive grammar, was an anal-retentive shibboleth of a by-gone era. My guess is that the writer who objected to having his grammar corrected had, uh, recently had his grammar corrected.

Now we all know that voice is important, and that it would be ridiculous to assign conventionally correct grammar to certain characters. I mentioned in a previous column the anecdote told by my good friend Gary Phillips, who writes very urban crime stories, concerning the earnest young editor who corrected his gangsta characters’ dialogue to conform to Good English. Now, that was plainly insane. And was it Westlake or Leonard who said when forced to make a choice, he’d go with clarity over grammar?

Well, I don’t know. Personally, it strikes me that the purpose of grammatical rules is to ensure clarity, and that you ignore them at your peril. The sticking point is that the standards of grammar, as with all things, change over time. I apparently inherited my Diction Cop gene from my paternal grandfather, who died a decade before my birth. By report, he would get nearly apoplectic if somebody said “It’s me” instead of “It is I.” But these days, the former expression is no longer looked upon as a sign of ignorance. It has made it into the language.

But some things clearly are ignorant. If I had written, “the purpose of grammatical rules are to ensure clarity,” I would be clearly guilty of violating subject/predicate agreement: the subject of the clause is “purpose”, singular, and not “rules”, plural—therefore, the verb must be “is”, singular, and not “are”, plural. But I wish I had a dime for every time I see such a violation in the newspaper these days. It is just plain wrong.

Or how about the following, written on the side of the cardboard box of Merlot sitting on my counter right now:

“As a third generation winemaker, the California wine country has always been a part of my life.”

What? The California wine country is a third generation winemaker?

This is a misplaced modifier, an adjectival clause pointing nowhere. The rule is that if you put the modifier after the subject and it doesn’t make sense, then putting it in front of the subject is also wrong: “The California wine country, as a third generation wine maker, has always been a part of my life.” But this is another practice that you will find “more honour’d in the breach than in the observance”, as Hamlet so piquantly put it. I think it’s insidious. It’s sloppy. Sloppy grammar leads to sloppy thinking. Sloppy thinking is the arch-enemy of clarity.

This is especially important in complex sentences, those that contain more than a single clause. For what it’s worth, there are five kinds of subordinate clause: subject, predicate, object, adjectival, and adverbial. The first three are sometimes called substantive clauses, since they serve the grammatical function of a noun in the sentences in which they appear, and “substantive” is Grammarian for “noun”. The other two, obviously, act as either an adjective or adverb–we might call them “modifier” clauses.

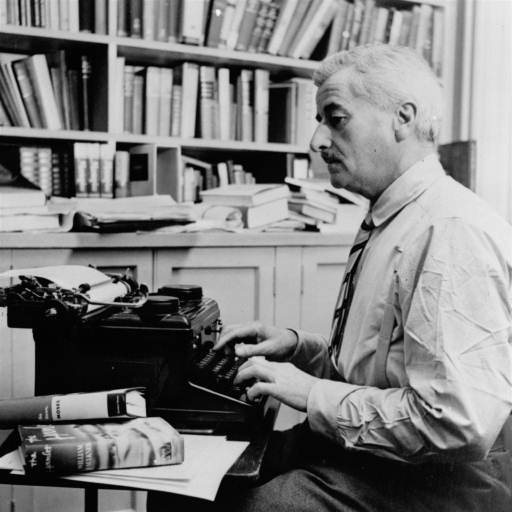

Sometimes strict rules of modifier placement may be played with, as long as there is a justification in terms of parallel structure. The following (extremely complex) example, from William Faulkner’s The Wild Palms, has a parallelistic structure that violates strict logic—by which I mean, not all of the modifiers apply to the nouns they formally ought to—but still maintains its grammatic integrity:

“So once more he stood on dry land . . . he and the woman standing on the empty levee, the sleeping child wrapped in the faded tunic and the grapevine painter still wrapped about the convict’s wrist, watching the steamboat . . . crawl onward up the platter-like reach of vacant water, burnished more and more to copper, its trailing smoke roiling in slow copper-edged gouts, thinning out along the water, fading, slinking away across the vast serene desolation, the boat growing smaller and smaller until it did not seem to crawl at all but to stand stationary in the airy substanceless sunset, dissolving into nothing like a pellet of floating mud.”

Francis Christensen and Bonniejean Christensen graph out the parallelism of this sentence in their book A New Rhetoric as follows:

1. So once more he stood on dry land . . .

2. he and the woman standing on the empty levee,

3. the sleeping child wrapped in the faded tunic

and

3. the grapevine painter still wrapped about the convict’s wrist,

3. watching the steamboat . . . crawl onward up the platter-like reach

of vacant water,

4. burnished more and more to copper,

4. its trailing smoke roiling in slow copper-edged gouts,

5. thinning out along the water,

5. fading,

5. slinking away across the vast serene desolation,

4. the boat growing smaller and smaller until it did not seem to

crawl at all but to stand stationary in the airy substanceless

sunset,

5. dissolving into nothing like a pellet of floating mud.

Now I ask you: could Faulkner have written that sentence if he didn’t know anything about grammar and the way it operates? Yes, he violated some simple rules, but that’s because he adhered to more complex ones in their stead, by structuring the sentence on several levels.

Now, the Gentle Reader is probably aware that I am not a Faulkner partisan. But that is a matter of personal taste on my part, not a criticism of his craft.

Sometimes we read that too much description is bad. We can certainly simplify the sentence by removing the adjectival clauses. What remains is this:

“So once more he stood on dry land watching the steamboat crawl on the water until it dissolved into nothing.”

Not a bad sentence, but it’s too simple to convey the original version’s hushed sense of suspended time. It’s just a guy staring at a boat. But maybe I’m being unfair by performing such radical surgery. We can simplify the grammar and still keep all the description by recasting the dependent adjectivals into independent sentences:

“So once more he stood on dry land. He and the woman stood on the empty levee. The sleeping child was wrapped in the faded tunic and the grapevine painter was still wrapped about the convict’s wrist. He watched the steamboat . . . crawl onward up the platter-like reach of vacant water. It burnished more and more to copper. Its trailing smoke roiled in slow copper-edged gouts. The smoke thinned out along the water, fading, slinking away across the vast serene desolation. The boat grew smaller and smaller until it did not seem to crawl at all but to stand stationary, dissolving into nothing like a pellet of floating mud in the airy substanceless sunset.”

As far as I’m concerned, the poetic cadence of the passage is completely destroyed and its emotive power is dealt up in easy-to-swallow bite-sized slices. Instead of seeming like a single experience, it has become a series of events. The feeling of suspended time is again sacrificed.

There isn’t anything wrong with good, plain English, of course. The length of a sentence should serve a purpose, and here, I think it does. The slow and gradual disappearance of the boat is like a long continuous shot in a film, meant to be experienced as a single image and not in rock-video snippets. Not every writer would attempt it and many would have little use for it. That’s not my point. My point is the reason Faulkner got away with it is because he knew what he was doing.

And that’s why it’s important that a writer know about grammar—not that he be punctiliously correct, but that he might use the way language works to his advantage. And that’s also why it’s good to have readers who appreciate what it is they’re reading, so that they can savor the full flavor of a story.

Great post! (If only I’d listened in grade school!) Now, may I switch gears for a moment and offer a toast to Edgar Allan Poe on his 200th birthday? Forgotten Author? Nevermore! For gosh sakes, grade school kids like reading him!

Hey, Jeff! Thanks for the reminder.

It is a great post, James. I admire the phrase “too simple to convey the original version’s hushed sense of suspended time.”

There used to be another branch of classical education, dialectic, which is related to logic. Each component is like a table leg in that each helps support the structure. Good grammar makes the others possible.

After that post which I read I say my head hurts lots.

How appropriate, that your “extremely complex” example came from Faulkner.

Great column! There are points here that we’d all do well to remember.

I believe the observation you mentioned, about clarity vs. grammar, was Leonard’s, but I can easily see either him or Westlake making it. And I think it was Loren Estleman who said (I’m paraphrasing, here): “If a rule gets in the way of the crystal flow of a good clear sentence, run right over it.” But the rules are, indeed, there for a reason.

Ah, James, when will this Gentle Reader learn that your posts are to be read in late afternoon rather than morning when the day’s work is about to begin? Now I lack the courage to strike even a single key.

Still, I am in your debt for teaching me things I missed during my formative years spent in the shadow of Goodyear Plant One on the cruel streets of East Akron. Just knowing a conjunction from an adverb would have placed a boy in danger of a trouncing from his peers.

Despite all that, I have to say I understood exactly what the winemaker was saying. Doesn’t that mean he did an acceptable job of writing? While Faulkner’s paragraph or sentence, whatever it happened to be, left me at a complete loss, your “So once more he stood on dry land watching the steamboat crawl on the water until it dissolved into nothing” painted a vivid picture in my mind.

Whatever, it was a great post and I thoroughly enjoyed it. I do have one question: In California do you drink merlot from a cardboard box? Why not, it works for orange juice.

This piece appealed to the English teacher in me. Dangling and misplaced modifiers are especially annoying, even when the writer’s meaning is clear, as (in the example given) it usually is. Differences between American and British English are a constantly intriguing topic. In recent years, some atrocities that American language purists are still fighting (e.g., “Everyone has a right to their own opinion” or “She has a bigger vocabulary than him”) now seem to be completely acceptable to cultured British writers. There is one British practice I’ve always admired for its logic: when a singular noun implies a plural, it is paired with a plural verb (e.g., “The jury are deliberating”). Where an American writer might say, “Simon and Schuster is my publisher,” a British writer might say, “Michael Joseph are my publishers.” And why does it make sense to say the Lakers are playing the Celtics, but the Jazz is playing the Sonics?

When you wrote:

Now see, in my previous comment, I failed to follow the rules of HTML grammar, and look what happened. I have a blockquote within a blockquote. I apologize for my sloppiness and lack of clarity.

Dick, your point about the winemaker’s meaning being clear is true, but my problem with it is that by throwing in that misplaced modifier, he’s accepting its use as valid. In some other context, the misplaced modifier might be very confusing. That’s why I say using it encourages sloppy thinking.

But as to your more important point, the wine is actually in a plastic bladder and the bladder is inside the box. You get at the vino by way of a plastic bung sticking out of one of the sides of the box. There’s some really good box wine out there these days, although mine is cheap plonk.

My favorite example of a misplaced modifier: “We make combs for people with unbreakable teeth.”

Remember? “A mind is a terrible thing to waste.”