Monday, June 11: The Scribbler

WATCH WORDS

by James Lincoln Warren

My good friend screenwriter and short story author Paul Guyot has made occasional forays into the blogosphere, first with his very popular but now long-defunct blog Ink Slinger, which dispensed advice to screenwriters, and more recently as a former bi-weekly guest contributor to Murderati, where he touched upon more general aspects of the writing life.

Paul is a man of many passions and one of them is collecting watches. (“Time is too important to measured by a cheap watch.”) One of the more amusing features he included in his ramblings on Murderati was assigning fine watches to series protagonists in crime fiction. This might seem a wholly trivial thing, but one of the hallmarks of a well-realized character is how well details of taste and judgment reveal him to us, and by extension, how well we apprehend such details to judge the consistency of his behavior—said another way, we can judge how convincingly a character is drawn in some degree by how well we intuit the choices he will make. In this light, Paul’s game wasn’t trivial at all. In fact, many of the writers wrote Paul to inform him that his choices were dead on.

He never gave a watch to my detective Alan Treviscoe, for two reasons: (1) Treviscoe is far below the stature of the detectives Paul gave chronographs to, who were folks like Barry Eisler’s John Rain, Cara Black’s Aimée Leduc, Lee Child’s Jack Reacher, S.J. Rozan’s Bill Smith and others, and (2) Treviscoe already had a watch, made by 18th century watchmaker John Jefferys, which incorporated many horological innovations introduced by John Harrison, inventor of the marine chronometer.

A few days ago, I asked Paul to pick a watch for me. I told him price was not a consideration, since I’m sure I wouldn’t be able to afford it any more than I can afford my ideal automobile (a 1929 Duesenberg SJ with a Murphy coach, thanks for asking),

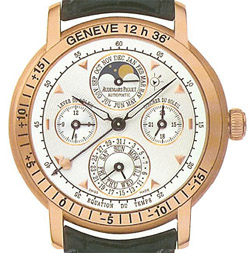

and that I wanted the perfect watch based solely on his perception of my personality. And Paul came through, recommending the Jules Audemars Equation of Time, an attractive tchachki priced between $38,000 and $100,000. (That’s still considerably less than the Duesenberg.)

Why did he pick that particular timepiece? Because it has certain features that Paul knew would greatly appeal to me: it shows the difference between solar time and zone time (called the “equation of time” and the source of the watch’s designation), predicts sunset and sunrise, shows the phases of the moon, and has a four-year perpetual calendar, not to mention bitchin’ good looks. (The only flaw is the lack of a sweep second hand, something that is of great utility to navigators, as once I was.)

The equation of time feature was especially intriguing, and I wondered if Paul had admired a story of mine (“The Apollo Progression”, AHMM, November 2005) that more or less features this phenomenon, until I remembered that I had written the story for Paul in the first place, for a prospective anthology on timepieces and crime that David Montgomery and he had pitched as co-editors.

One of my rules for writing short stories is, “Make the reader do most of the work,” by which I mean engaging the reader’s imagination to automatically fill in gaps in narrative and description. The easiest way to do this is by providing discrete details in lieu of general information—e.g., what kind of shoes the character wears without mentioning the rest of his wardrobe. A guy wearing steel-toed Wolverines is not going to be wearing a tuxedo. A woman in Manolo Blahniks probably won’t be wearing a lunch lady’s uniform.

Jewelry is even better. There is nothing more personal. It conveys almost everything you want to know—whether persons are vain or modest, how refined or faddish their tastes run, how deep their sentiments penetrate, what their socioeconomic brackets are, if they have subcultural inclinations, how they assign their priorities, and on and on.

A 24-carat gold horseshoe diamond ring on a pinky says something very different from a stainless steel circular barbell through a nasal septum.

But nothing says more than a watch. Even the absence of a watch—albeit sometimes combined with whether or not the character has a cellphone grafted to his head—tells you a lot.

I could go on, but just look at the time.

You had me hooked with Duesenberg, indeed the entire ACD line. And Packards of the era, and the 1928 Mercedes SSK.

But a watch… I must be timeless.

A timely article indeed. You always surprise me.

Ah, the sweep second hand… I assumed one such as yourself, who lingers to whiff the proverbial roses, would not care to be reminded of seconds sweeping by.

I must say, coming in a close second to the EOT for you, was the Breguet Pocket Watch No. 5. It does have your seconds swept, but only six pieces were ever created. And we know JLW is not that ostentatious. Well….

ACD (“Auburn Cord Duesenberg”) is not to be confused with OCD, or maybe it is.

Anybody tooling around in a Duesy is certainly ostentatious enough for a Breguet No. 5, as Paul gently hints. Yes, he knows me all too well. A No. 5 was recently sold for $600,000, still not as much as a Duesenberg, but the Duesenberg doesn’t have a sweep second hand, either.

I was actually expecting a Breguet. Alexander Pushkin’s Yevgeny Onegin used one, and Patrick O’Brian’s Stephen Maturin has his Breguet stolen by a privateer in Post Captain, the second volume in the Aubrey-Maturin series of Napoleonic nautical adventures, and Jules Verne’s Phileas Fogg clocked his famous 80-day journey with his. Among nonfictional owners, the list includes Wellington, Washington, and Tolstoy. But the Jules Audemars does say more about my character, since any very rich man might sport the ravishing Breguet simply as a kind of horological trophy wife.

I was sure that either Debby or Melodie was going to say something about the Manolo Blahniks, though.

Yes, see, the reason I chose the Audermars over the Breguet is because the Breguet was obvious.

That was before I learned of your unnatural attraction to sweep second hands.

Actually, navigators use stop watches synchronized to the ship’s chronometer to measure seconds when shooting star sights, and the ship’s clock to measure them when shooting terrestrial bearings, so the navigator’s watch doesn’t really need a sweep second hand at all.

Then shut up and enjoy your Audemars.