Monday, September 14: The Scribbler & Mystery Masterclass

Here is Chapter VI and the Conclusion to Pushkin’s famous novelette, “The Queen of Spades”. I’ve appended a brief afterword.

—JLW

THE QUEEN OF SPADES

by Alexander Pushkin

VI

“Attendez!1”

“How dare you say ‘attendez’ to me?”

“Your excellency, I said ‘attendez, sir.’”2

Two fixed ideas can no more exist together in the moral world than two bodies can occupy one and the same physical world. “Three, seven, ace” soon drove out of Hermann’s mind the thought of the dead Countess. “Three, seven, ace” were perpetually running through his head, and continually being repeated by his lips. If he saw a young girl, he would say: “How slender she is; quite like the three of hearts.” If anybody asked “What is the time?” he would reply: “Five minutes to seven.” Every stout man that he saw reminded him of the ace. “Three, seven, ace” haunted him in his sleep, and assumed all possible shapes. The threes bloomed before him in the forms of magnificent flowers, the sevens were represented by Gothic portals, and the aces became transformed into gigantic spiders. One thought alone occupied his whole mind — to make a profitable use of the secret which he had purchased so dearly. He thought of applying for a furlough so as to travel abroad. He wanted to go to Paris and tempt fortune in some gambling houses that abounded there. Chance spared him all this trouble.

There was in Moscow a society of rich gamesters, presided over by the celebrated Chekalinsky, who had passed all his life at the card table, and had amassed millions, accepting bills of exchange for his winnings, and paying his losses in ready money. His long experience secured for him the confidence of his companions, and his open house, his famous cook, and his agreeable and fascinating manners, gained for him the respect of the public. He came to St. Petersburg. The young men of the capital flocked to his rooms, forgetting balls for cards, and preferring the emotions of faro to the seductions of flirting. Narumov conducted Hermann to Chekalinsky’s residence.

They passed through a suite of rooms, filled with attentive domestics. The place was crowded. Generals and Privy Counsellors were playing at whist, young men were lolling carelessly upon the velvet-covered sofas, eating ices and smoking pipes. In the drawing-room, at the head of a long table, around which were assembled about a score of players, sat the master of the house keeping the bank. He was a man of about sixty years of age, of a very dignified appearance; his head was covered with silvery white hair; his full, florid countenance expressed good-nature, and his eyes twinkled with a perpetual smile. Narumov introduced Hermann to him. Chekalinsky shook him by the hand in a friendly manner, requested him not to stand on ceremony, and then went on dealing.

The game occupied some time. On the table lay more than thirty cards. Chekalinsky paused after each throw, in order to give the players time to arrange their cards and note down their losses, listened politely to their requests, and more politely still, straightened the corners of cards that some player’s hand had chanced to bend. At last the game was finished. Chekalinsky shuffled the cards, and prepared to deal again.

“Will you allow me to take a card?” said Hermann, stretching out his hand from behind a stout gentleman who was punting.

Chekalinsky smiled and bowed silently, as a sign of acquiescence. Narumov laughingly congratulated Hermann on his abjuration of that abstention from cards which he had practised for so long a period, and wished him a lucky beginning.

“Stake!” said Hermann, writing some figures with chalk on the back of his card.

“How much?” asked the banker, contracting the muscles of his eyes, “excuse me, I cannot see quite clearly.”

“Forty-seven thousand rubles,” replied Hermann. At these words every head in the room turned suddenly round, and all eyes were fixed upon Hermann.

“He has taken leave of his senses!” thought Narumov.

“Allow me to inform you,” said Chekalinsky, with his eternal smile, “that you are playing very high; nobody here has ever staked more than two hundred and seventy-five roubles at once.”

“Very well,” replied Hermann, “but do you accept my card or not?”

Chekalinsky bowed in token of consent.

“I only wish to observe,” said he, “that although I have the greatest confidence in my friends, I can only play against ready money. For my own part I am quite convinced that your word is sufficient, but for the sake of the order of the game, and to facilitate the reckoning up, I must ask you to put the money on your card.”

Hermann drew from his pocket a bank-note, and handed it to Chekalinsky, who, after examining it in a cursory manner, placed it on Hermann’s card.

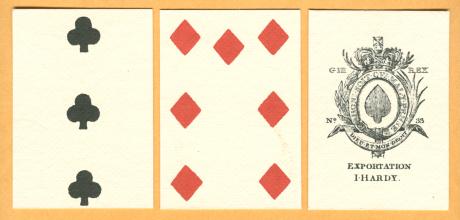

He began to deal. On the right a nine turned up, and on the left a three.

“I have won!” said Hermann, showing his card.

A murmur of astonishment arose among the players. Chekalinsky frowned, but the smile quickly returned to his face. “Do you wish me to settle with you?” he said to Hermann.

“If you please,” replied the latter.

Chekalinsky drew from his pocket a number of banknotes and paid at once. Hermann took up his money and left the table. Narumov could not recover from his astonishment. Hermann drank a glass of lemonade and returned home.

The next evening he again repaired to Chekalinsky’s. The host was dealing. Hermann walked up to the table; the punters immediately made room for him. Chekalinsky greeted him with a gracious bow.

Hermann waited for the next deal, took a card and placed upon it his forty-seven thousand roubles, together with his winnings of the previous evening.

Chekalinsky began to deal. A knave turned up on the right, a seven on the left.

Hermann showed his seven.

There was a general exclamation. Chekalinsky was evidently ill at ease, but he counted out the ninety-four thousand roubles and handed them over to Hermann, who pocketed them in the coolest manner possible, and immediately left the house.

The next evening Hermann appeared again at the table. Everyone was expecting him. The generals and privy counsellors left their whist in order to watch such extraordinary play. The young officers quitted their sofas, and even the servants crowded into the room. All pressed round Hermann. The other players left off punting, impatient to see how it would end. Hermann stood at the table, and prepared to play alone against the pale, but still smiling Chekalinsky. Each opened a pack of cards. Chekalinsky shuffled. Hermann took a card and covered it with a pile of bank-notes. It was like a duel. Deep silence reigned around.

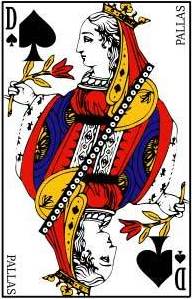

Chekalinsky began to deal, his hands trembled. On the right a queen turned up, and on the left an ace.

“Ace has won!” cried Hermann, showing his card.

“Your queen has lost,” said Chekalinsky, politely.

Hermann started; instead of an ace, there lay before him the queen of spades! He could not believe his eyes, nor could he understand how he had made such a mistake.

At that moment it seemed to him that the queen of spades smiled ironically, and winked her eye at him. He was struck by her remarkable resemblance. . . .

“The old woman!” he exclaimed, seized with terror. Chekalinsky gathered up his winnings. For some time Hermann remained perfectly motionless. When at last he left the table, there was a general commotion in the room.

“Splendidly punted!” said the players. Chekalinsky shuffled the cards afresh, and the game went on as usual.

Conclusion

Hermann went out of his mind, and is now confined in the Obukhovsky Hospital, room number seventeen. He never answers any questions, but he constantly mutters with unusual rapidity: “Three, seven, ace! Three, seven, queen!”

Lizaveta Ivanovna married a very amiable young man, the son of he old Countess’s former steward. He is in the service of the State somewhere, and is in receipt of a good income. Lizaveta is also supporting a poor relative.

Tomsky has been promoted to the rank of captain, and has married the Princess Pauline.

To me, far more than the appearance of the Countess’s ghost, the succession of cards is the most supernatural element in the story. The probability of the sequence described (a 3 of any suit, a 7 of any suit, and the Queen of Spades) is just a sliver better than 1 in 9,000 — well beyond credibility. On the other hand, we have only the narrator’s word for it that the first two cards played are actually the ones Hermann expects, since he deliberately does not disclose his guilty secret to anyone — and we already know that he becomes mentally unhinged by the end of the story, if not much sooner, when he has his vision. Psychologically it is entirely possible that as long as he won, he might retroactively believe that the winning cards were the ones the Countess’s ghost had told him about. In that case, assuming that both players have an equal chance of winning, the odds of one of them winning both of two sequential hands fall to 1 in 4. That leaves only the last card, the Queen of Spades, where the probability is 1 in 52. Taken together, this reduces the mathematical probability of the scenario as described to about 1 in 200. Still long odds, but not inconceivable.

Even so, none of this is important. The fall of the cards is not a coincidence — Justice might be blind, but she doesn’t roll dice. The irony of the last card is necessary for justice be served. After all, fiction has more rules than real life. The final turn of events is what makes this such a satisfying story.

Writers make choices. Unlike cards, good stories are not random. The skilled story-teller, though, fades into his narrative in such a way that it never occurs to you that he’s actually lying. This is what Coleridge meant when he wrote about the suspension of disbelief, but not every writer is clever enough to sustain that suspension. The better the story-teller, the less likely we are to question what he tells us. This is especially true of characterization — there is nothing more jarring than a fictional character behaving in an manner inconsistent with what the Gentle Reader has been led to expect, even though real people do it all the time.

But that’s a topic for another column.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading “The Queen of Spades” as much as I enjoyed presenting it. Please let me know if my little expedition into “lit crit” was constructive enough to justify another such trip sometime. If it wasn’t, then let me know that, too. We aims to please — the one cardinal sin of a writer is to write things nobody wants to read.

- “Wait!”

[↩]

- Michael J. Cummings, a freelance writer and former college instructor who maintains a study guide site for important works of literature, has this to say about this quote:

“The reply of the important person appears to be one that Napoleon might have had made when addressed improperly by an underling. Hermann, of course, has become like Napoleon in his obsession to conquer the world of cards.”

Personally, I find this a bit of a stretch, even though Tomsky compared Hermann to Napoleon a couple of chapters ago. I rather think it’s an example of Pushkin’s often-impish sense of humor, which has been on display once before, at the Countess’s funeral when the Englishman is told, completely erroneously, that Hermann is the Countess’s bastard.

Nevertheless, Cummings’ point that the pompous person to whom the imperative “Wait!” is addressed suffers from self-importance is entirely valid. Napoleon notwithstanding, the quote hints that Hermann is hopelessly lost in the grip of a narcissistic obsession.

[↩]

Great story so posting more would be an excellent move.

What other authors/stories would people be interested in reading and discussing? I, for one, would enjoy discussing anything by Borges.