Monday, November 15: The Scribbler

HEARING VOICES

by James Lincoln Warren

Any scribe worthy of a paycheck works hard to make sure that his characters all speak differently from each other. Having everybody use exactly the same diction is boring and unrealistic. Where it becomes hardest to consistently keep a character’s voice unique isn’t in dialogue, though, it’s in a first person narrative. This is because the author, being a wordsmith, directly impinges on the character’s mode of expression. Most of my stuff is in the third person limited POV, but I have several stories in the first person—the first story I ever sold was told in the first person. I try to make them as different from me as they are from each other, but I don’t always succeed.

Here’s an excerpt from “The Warcoombe Witch” (AHMM, Nov 2008). It’s a double-first, because the text is supposed to be an excerpt from one character’s diary describing another character’s telling a story:

“On the Edge of this Hamlet, on the Squire’s side, there lived an ancient Crone named Jane Thornwold, who had some local Infamy as a Cunning-woman. She dwelt alone, except for a Family of tame Crowes, a nastie grey Tabbie Cat, and an abominable brindled Mastiff, in a decrepit Hovel, that had during the previous Century been a fine Cottage, but was now blackened with Soot & Age, and had long since fallen into Ruin.

“Her History was, that in the Days of Charles II., she had been a magnificent Beauty, tall as a Yew, with billowing black Hair like an April Thundercloud, and shining Eyes that verily flashed with Lightning,” Ambury told us, with a fine Ear for Poesy.

This one was easy in a way. Ambury is telling his story in 1750 and uses 18th century sentence structure. The recorder, whose name is never given, follows the orthographic customs of his age. All right, maybe imitating language 250 years old takes some research and a keen ear, but the personality of the character pretty much takes care of itself.

Here’s another excerpt, from “Shanghaied” (AHMM Jan/Feb 2009).

One thing I’ve noticed about lunacy is that it can be catchier than a tune in a minstrel show. It’s got its own crazy rhythm that infects everybody around. The sailors climbed the ratlines as quiet as moss growing on a tombstone, their eyes wide as lenses on a lighthouse, grinning like a bunch of Jolly Rogers. Not a sound was heared except for the scuffling of bare feet on the white oak planks, the turn of the capstan, the creaking of cordage and strakes under strain, and the whisper of water against the hull. Even the sails was lowered as careful as you might let a baby basket out a window. It was like our captain was the Angel of Death, sailing off to collect dumb souls from out of the deep.

The narrator is my version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Davy Balfour in Kidnapped, but whereas his Davy was a serious and decent 18th century Scots Presbyterian, mine’s a 19th century California guttersnipe. Obviously, my model for the tone of the language was Huckleberry Finn. Again, I did some careful wordsmithing to catch the right flavor, but the character came easily out of the words themselves.

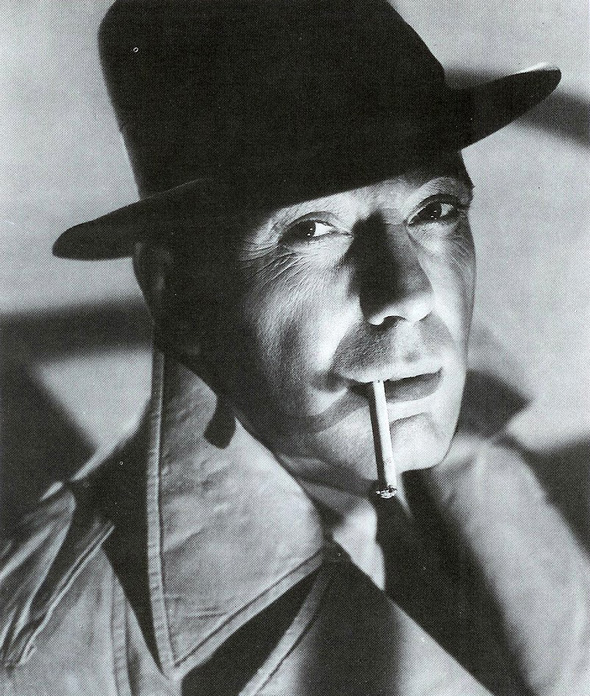

Finally, here’s Carmine Ferrari of Cal Ops in “Cold Reason” (AHMM Apr 2008).

Little old Stanley Stowicz is the only guy I know who buys the newspaper for the chess column. I don’t mind chess. My brother Joe, the Ferrari family boy genius, taught me how to move the pieces when I was a kid back in New York, and explained things like castling and discovered check. That’s as far as I got. Barroom billiards turned out to be a lot more my speed. To me, a Sicilian defense is the Fifth Amendment.

Not hard to tell that Carmine is a tough P.I., is it? His spiel has all the hallmarks. I have fun writing as Carmine, but I think I may have fallen into a trap.

Here’s an excerpt from a work in progress:

Dad desperately wanted me back—you know what some fathers are like when it comes to their little princesses, not that I’m remotely little or have ever been anything like a princess—but he wanted me home, in Fresno in general and at Sherwood Brothers in particular. I might mention that our name isn’t Sherwood and I don’t have any brothers, but when Dad formed the business, he decided there should be “wood” in the name somewhere, and the Robin Hood and his Merry Men angle struck him as cute. Like cute is a big part of the bail bonds business. As far as I’m concerned, drop the Robins and what you’re left with is the Hoods.

See the problem?

The narrator, whose name is Erica H. Wooding, is obviously young and female and smart.

So how come she sounds like Carmine Ferrari, who is close to middle age and male and although not stupid, not any kind of a genius?

Furthermore, Erica is only a high school graduate and Carmine has a Master’s Degree. A lot of how people sound when they talk is determined by their educations. Not here, though.

Or is it that they both sound like me? I am neither female nor young, being at the other end of middle age than Carmine, nor do I have a Master’s Degree, although I’d like to think I have a modicum of brains.

Or is it something worse?

Could it be that they sound alike because they’re both formulaic?

When I first looked at that last passage a few hours ago right after firing up the old computer, I said to myself, “It sounds like the opening of a detective story.”

Not exactly what I wanted. Yes, it is going to be a detective story, but first and foremost it should be Erica’s story. I think I’ve let her down.

In other words, maybe there’s no character there at all. So I think I get to know Erica a little bit better before I start giving her wisecracks. Maybe I ought to make her a little less forthright, although self-confidence has to be one of her most salient characteristics for the story to work. Confidence isn’t always expressed in the same way, after all. Sometimes it’s brash and sometimes it’s subtle. Erica is probably somewhere in between.

So what I have to do is start listening to voices. Melodie suggested that I buy a copy of Elle magazine to see what kind of clothes Erica wears. (Good advice, that.) I also better tune in to what women in their twenties are saying, although God forbid that Erica ends up spouting clichés in a Valley Girl whine. This is a bit more challenging than writing 18th century sentences, because I don’t know a lot of women in their twenties. But do I have young male acquaintances with wives and girlfriends, so I can listen to them instead—they may not be able to tell me what their wives and girlfriends actually say verbatim, but they can tell me what they hear, which in some ways is even better.

A writer does not only have to know how to read. He has to know how to listen. So now I’m going to shut up.