Sunday, September 20: The A.D.D. Detective

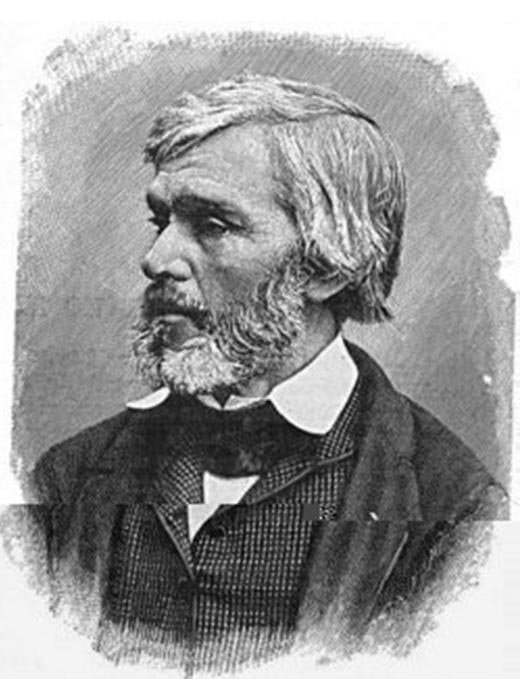

THOMAS CARLYLE

by Leigh Lundin

Thomas Carlyle, the Scottish essayist, historian, and satirist, pivotally influenced English literature, but there’s an important lesson of his that stands out in the literary world:

Make backups! Back up your data. Back it up to a CD, a DVD, a keychain flash drive, but make backups. Back up frequently. Store them in safe places. Consider keeping a copy ‘off site’ as computer people say. If you haven’t learned the lesson the hard way, you will. Backups! Trust me.

Okaaay, great idea, but what does backing up your manuscript files on permanent media or flash drives have to do with a man born in 1795?

Personal Life

Carlyle was noted for a crabby and cantankerous demeanor, but with some reason. Determined their son should attend school, his Calvinist family scrimped for boarding fees and tuition only to find Thomas bullied and harassed. Departing after only three years, Carlyle went on to the University of Edinburgh, but early bullying and a subsequent crisis of religious faith may have led to a gastric ulcer. He developed a painful stomach ailment that remained throughout his life and contributed to his reputation as a crusty, crotchety, and somewhat disagreeable personality. His prose style, famously fractious and occasionally savage, helped seal a reputation of irascibility.

Although Carlyle began to meet with literary success, fate continued to be unkind in his personal life. In 1821, he met Jane Welsh, an acidic, equally ill-tempered fellow writer. They married in 1826, creating one of the most famous, well documented, and unhappy of literary unions. Some nine thousand letters between Carlyle and his wife show an affection for one another harmed by frequent and angry arguments.

As Samuel Butler said, "It was very good of God to let Carlyle and Mrs Carlyle marry one another, and so make only two people miserable and not four."

Burning Words

Carlyle began work on a three volume poetic history of the French Revolution. After more than a year’s work, Carlyle sent volume I for critique to his friend John Stuart Mill, the economist, liberal philosopher and political theorist. Mill’s cleaning lady came across this stack of paper and, seeing it was old and scribbled on, concluded the used paper was scrap and burned it. Up in flames. As in Fahrenheit 451°.

Carlyle was devastated, not merely for the lost of his effort, but because he’d had no income for months and was virtually penniless. Carlyle told his wife: "We must try to hide from Mill how very serious this business is to us." Much later, G. B. Tennyson wrote Carlyle reported "I just felt like a man swimming without water."

He soldiered on, completing volumes II and III, and returned to rewrite volume I. He published the completed work, The French Revolution, in 1837, but Carlyle was so poor, he turned to teaching, a job he believed he was poorly suited for. He wrote, "O heaven! I cannot speak. I can only gasp and write and stutter, a spectacle to gods and fashionables, being forced to it by want of money."

But besides an impressive legacy of works, Carlyle also leaves us the bit of wisdom:

Make backups!

Dragnet

You might wonder what Thomas Carlyle and Jack Webb’s Dragnet have in common. In watching episodes of Dragnet from the early 1950s, I was struck by a couple of things. First, Dragnet’s a pretty good police procedural for the era, much more interesting than its competitor Code 3. Secondly, I noticed how the directors stalled for time when plots invariably ran thin. In one case, Dragnet interrupted a scene while a realtor spent a full minute answering a phone call, failing to advance the story one whit, obviously filling in time.

You might wonder what Thomas Carlyle and Jack Webb’s Dragnet have in common. In watching episodes of Dragnet from the early 1950s, I was struck by a couple of things. First, Dragnet’s a pretty good police procedural for the era, much more interesting than its competitor Code 3. Secondly, I noticed how the directors stalled for time when plots invariably ran thin. In one case, Dragnet interrupted a scene while a realtor spent a full minute answering a phone call, failing to advance the story one whit, obviously filling in time.

An episode called The Big Oskar features an interesting robbery victim who happens to be the editor of a weekly ‘throw-away’ shopper newspaper, but an editor who takes her job seriously. She mentions in passing that "Tom Carlyle" fell victim to an over-zealous cleaning maid, telling the story of the cleaning lady who came across Carlyle’s manuscript for his first volume of the history of The French Revolution and discarded. "The paper wasn’t useful anymore… it was already written on."

That’s how a crime writer relates back to Thomas Carlyle.

It’s also wise to transfer everything on a flash drive to a CD as quickly as possible. They can go bad.

As Carlyle was not a calm and cool man I would not have wanted to be in the same room when he heard about the burned manuscript. It’s a little surprising the incident was mentioned on Dragnet. Guess you never know.

I think it’s a bit of a stretch to say that Carlyle “pivotally influenced English literature”. You can take many a survey of 19th century English lit without touching on him at all. He’s a more important figure in the history of ideas, where his historiography is regarded as exemplifying British Victorian attitudes toward Imperial Britain’s place in the world.

Carlyle’s theory of history, as put forth in his book On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History, was that history is the result of the acts of great men. It is most frequently contrasted with the diametrically opposed theory of Tolstoy, espoused in War and Peace, that history is the product of the ebb and flow of the masses and that so-called “great men” are like corks bobbing on the surface, highly visible but whose influence on events is entirely illusory.

Neither theory is currently in vogue, since both are now viewed as being hopelessly simplistic, but a slight edge might be given to Tolstoy insofar as most historical research these days concentrates on demographics and statistical analysis rather than on political decisions.

I was thinking along the lines of the portrayal of his characters’ and his own innermost thoughts and feelings, which shocked some sensibilities of his time. Publication of personal letters and his official biography (by Froude) outraged his family, but their arguments were difficult as this was exactly as Carlyle behaved.

(An argument could be made the emo generation, MySpace, FaceBook, and Twitter could trace their roots back to Carlyle.)

Carlyle made his early reputation by bringing Germanic romanticists to English attention. Carlyle was also an early sage writer, not that I’m impressed but he seems to have influenced Tom Wolfe and Norman Mailer.

I agree with Dick: magnetic and memory media are called ‘volatile’ for a reason. CDs and DVDs are the surest, safest media.

I didn’t mean to trivialize him, but pivotal figures are the ones that divide their fields into “before” and “after”. I don’t think you can honestly break Brit Lit into before Carlyle and after Carlyle. The giant of 19th century British literature was clearly Charles Dickens.

Agreed. Clearly.

Although we share our great fondness for Victorian mystery writers.

Absolutely!

Not that it’s particularly on point, but you might find the following intriguing:

The late Professor Al Hutter at UCLA taught a mystery fiction course, but his academic specialty was Dickens. He once opined to me that Dickens, and not Collins, was the original mystery novelist. All of Dickens’s books, except the Christmas stories, are about crimes that aren’t solved until the end of the novel. The difference, Al said, was that only one of Dickens’s books, Our Mutual Friend, has a “detective” who brings the villain to justice. (There’s a character who is a police detective in Bleak House, but he doesn’t solve the puzzle.)

Am mostly unfamiliar with Carlyle, but the story was spoofed in “Blackadder The Third” where a servant burns Dr Johnson’s MS of the Dictionary. Oh, yeah, Viva Charles Dickens!!!