Monday, July 11: Spirit of the Law

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

by Janice Law

“What’s in a name?” asked Juliet, but she was being disingenuous, knowing quite well the vast difference between being Juliet of the Scullery and the heiress of the Capulets. Her creator surely knew, too. While many of his characters’ names were set by history and legend, he let his imagination run when he could, especially with comic characters: Falstaff, Feste, Andrew Aguecheek, Toby Belch, (all Twelfth Night), Dogberry (Much Ado About Nothing), and Bottom (A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream), all not only funny, but apt.

No one who doesn’t write, and probably not even non-fiction writers, knows how important the right character name can be. Ideas can float in and out, but without le nom juste, they’re not going to grow, certainly not into something as luxuriant as Ebenezer Scrooge. But Dickens was not only one of the great plotters, he was one of the great namers: Harold Skimpole of Bleak House is very nearly in the Scrooge category. And who couldn’t run (literarily speaking) with Wackford Squeers (Nicholas Nickleby), Magwich (Great Expectations), or Bounderby and Gradgrind of Hard Times?

Names like those are money in the wordsmith’s bank. Modern preferences for realism have dampened such Victorian efflorescence, but there are exceptions. Thomas Pyncheon, he of the reclusive habits and massive tomes, has contributed both Pirate Prentice and Tyrone Slothrop (Gravity’s Rainbow) to posterity, not to mention Benny Profane and the Whole Sick Crew, both name and catchphrase in V.

His mystery counterpart has to be Carl Hiaasen. Hiaasen is a plotter par excellence with a truly antic imagination. Reading him is rather like eating a whole meal of marzipan topped off with a chocolate Sunday, but his character names are envy producing: Honey Santana (Nature Girl), Jimmy Stoma of Jimmy and the Slut Puppies (Basket Case) and from his latest, Star Island, the trio of Cherry Pye, Bang Abbott, and Skink.

Funny writers may have more opportunities for fanciful names, but some less hyper scribes have come up with good ones, too. Like Melanie, I’m a big fan of The Long Goodbye and all the other Philip Marlowe mysteries. And how apt his name is. Philip, not only Biblical but apostolic, hints at the gumshoe’s not always well concealed idealism, while the original Marlowe was not only a playwright of genius but an Elizabethan spy. We can love Raymond Chandler for his detective’s name alone.

Other worlds, other names. Dorothy Sayers was also a dab hand at nomenclature, with characters like Old General Fentimen, whose death is the Unpleasantness in The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, Freddy Arbuthnot, of Strong Poison, and, of course, every feminist’s favorite, Harriet Vane, and the reliable duo of Lord Peter Wimsey and his invaluable manservant, Bunter. The names suggest P.G. Wodehouse territory, but if Sayers aspired to the same rarified social heights, she was still willing to venture into such the non-comic territories as shell shock and the struggle for women’s education.

So how does one pick a character name? Some are the gift of the gods. Riding along behind a NEMF truck in Pennsylvania, I came up with Edward Nempf, for a marsh keeper in a novel about a flooded Hartford five hundred years in the future. It seemed just odd enough and yet clearly an English language moniker. Another gift was Iris Weed, perhaps my best ever character, whom I imprudently killed off early in The Lost Diaries of Iris Weed. I liked Iris for the great Iris Murdoch and also for the goddess of the dawn, but Iris seemed too fancy and old fashioned until my husband covered a soccer game. One of the opposing players was a Ms. Weed. Perfecto!

Iris Weed and Edward Nempf are good for another reason, too. Much as I love Dickensian names, typing Martin Chuzzlewit or Peggotty over and over is, for a weak keyboardist like myself, asking for trouble. Make it evocative, but make it short is my mantra, and think about the typing involved. One of the good things about Anna Peters, who labored for me in eight novels, was that her name was easy to use. And to remember. Because, afflicted with continuity problems, I have a bad habit of altering minor character’s names from chapter to chapter.

This is not a problem with short stories and I have a certain affection for some concocted characters. Bren and the ‘holiday names’ of Danielle and Sabine seemed right for “Lying,” a little story about spring break gone wrong. Dwayne Nguyen seemed right for the Amerasian hero of “The Paradise Garden,” who was destined to be the counselor of a warrior princess and finds her, against all odds, while working as a gardener in Southern California.

I have only once gotten to use what I think of as fancy names, in a story called “The Ghostwriter,” when I had to invent not only the protagonist, Marv, but a best-selling author—Hilaire La Doux—his characters Lord Ostrucht and Lady Fergaine, and a magic sword, The Blade of Zermain. That was a good day’s work.

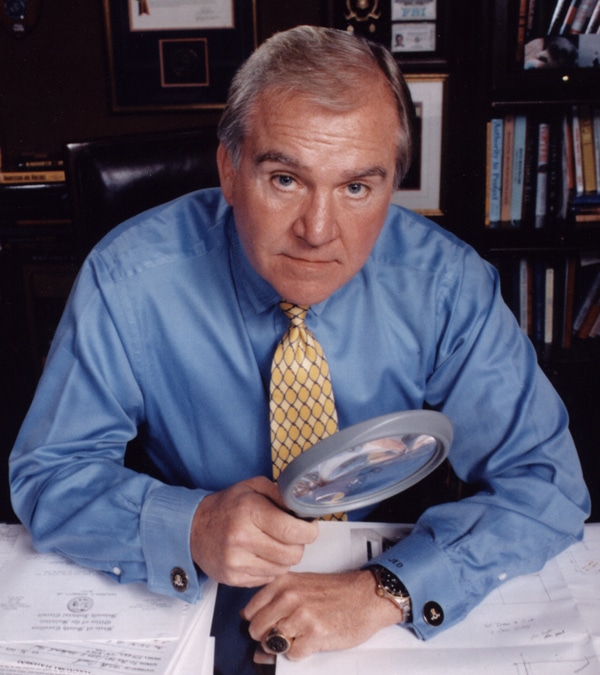

Click on picture to see more detail.

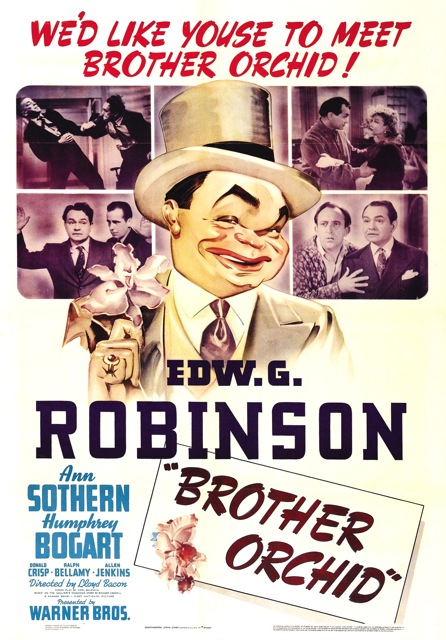

Click on picture to see more detail.