Monday, August 22: Spirit of the Law

THE TRICKY ART OF SUSPENSE

by Janice Law

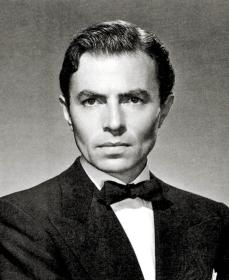

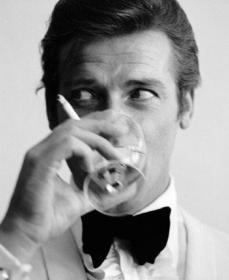

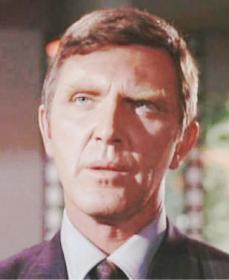

Joseph Cotton as Howard Graham, Everett Sloane as Kopeikin, and Orson Welles as Colonel Haki in the 1943 film version of Journey into Fear

Joseph Cotton as Howard Graham, Everett Sloane as Kopeikin, and Orson Welles as Colonel Haki in the 1943 film version of Journey into Fear

I used to tease some of the less enthusiastic readers in my sophomore level lit course that Jane Austen was one of the great masters of suspense. The women in the class found this amusing; they almost always found her novels funny and surprisingly relevant. The men in the class preferred Ralph Ellison and Charles Dickens and were inclined to reserve judgment on the Divine Jane’s suspense cred.

Clearly, a lack of imagination on their part! But correcting such deficiencies is what the classroom is all about. Consider the stakes, I used to point out: one wrong move and the heroine doesn’t just lose the guy, she loses her future. Think of the obstacles, poverty, disapproving relatives (most seriously those with the cash), and other young women out on the husband hunt. As for them, think lionesses on the veldt and you won’t go far wrong.

Still, a certain skepticism lingered that was not simply due to our 8 a.m. meeting time. Well, we can’t all be working writers, or for that matter, fast, enthusiastic readers, so some of Austen’s skill will go unnoticed. But consider that most of her heroines’ time is spent in chat, in visits, in social gatherings of greater or less boredom; that there were no car (or carriage) chases, no bodies in the basement, no shattering scandals and definitely no zombies, and that her people are, by and large, exceedingly polite, if not always well behaved, and you can see that she had her work cut out for her.

And how well she succeeds. How exquisitely she draws out crucial matters. Will she or won’t she succeed? Will he or won’t he show up? With what imagination she prolongs the resolution of her character’s difficulties, using the minutiae of social life to build a real drama, a drama on which her heroine’s whole future life teeters. On one side, success, a good marriage, a chance for happiness; on the other, disaster, the wrong man, misery, or almost worse yet, no marriage at all and a lifetime of dependency.

Austen had a talent for suspense, that is for prolonging a pleasurable uncertainty about favorite characters, even if she did not write what we’d now label ‘suspense’ novels. These have become a genre of their own, marked by a gargantuan exaggeration of danger ( saving the world—or at least a major city—is de rigueur) and featuring non-stop action, firepower, and high body counts, all within three inch-thick tomes.

It was not always thus. Consider the god of suspense, Eric Ambler. His classic Journey into Fear is a masterpiece that might, by today’s standards, be judged too light on action and too short by half.

The hero, Graham, is returning by ship to the UK from Turkey, where he has been working on an armaments contract. World War II has begun, and the night before embarkation he is almost murdered for his knowledge. Spirited aboard an obscure merchant vessel by the Turkish security forces, he appears to be safe, but after a brief stop in Athens, a new passenger comes aboard, the putative assassin.

Trapped on the boat and sure to be murdered when he leaves—if not before—Graham struggles to hide his fears, deceive the killer, and find a way of evening the odds.

For most of the novel, events are low key, a matter of awkward dinners, tense conversations, and uneasy meetings that have Graham wavering between near panic and nonchalance. Journey into Fear only needs violent action at the climax, because like Austen, Ambler was writing about a shame culture. Austen’s young ladies must watch for any compromising social misstep; Graham operates within a strong culture of courtesy and hierarchy. Unlike our present culture, where shamelessness is almost a requirement for celebrity, gentlemen in Graham’s world have a certain attitude and code of conduct to maintain.

Journey into Fear unfolds within a culture of restraint, privilege, and complacency that brings its own tensions. Graham fears embarrassment as well as death, and one of the features of the novel is the awkwardness of having to evade a killer while avoiding both discourtesy and ‘melodrama’.

Published in 1940, Journey into Fear records the end of one type of life and the erosion of the former security provided its subjects by the British Empire. Graham, neither an imaginative nor a particularly sensitive man, finds that the world he thought he knew is full of pitfalls, that he is not safe, that his death is highly desirable in certain quarters, and that, the Empire and the pound sterling notwithstanding, his British passport is no guarantee of protection.

Ambler traces Graham’s psychological evolution with great skill. He manages to make the duel between the intelligent amateur and the ruthless professional plausible, in part because there are no supermen and superwomen in his novels, only smart, interesting people whose fate we are eager to learn. His novels may no longer fit Suspense Novel category, but Eric Ambler writes suspense.