Monday, September 27: Mystery Masterclass

I was out of town this weekend, but my absence was more than compensated by this timely essay by Ellery Queen Expert (and Author!), previous CB contributor Dale Andrews. —JLW

THE ELLERY QUEEN MYSTERIES

by Dale C. Andrews

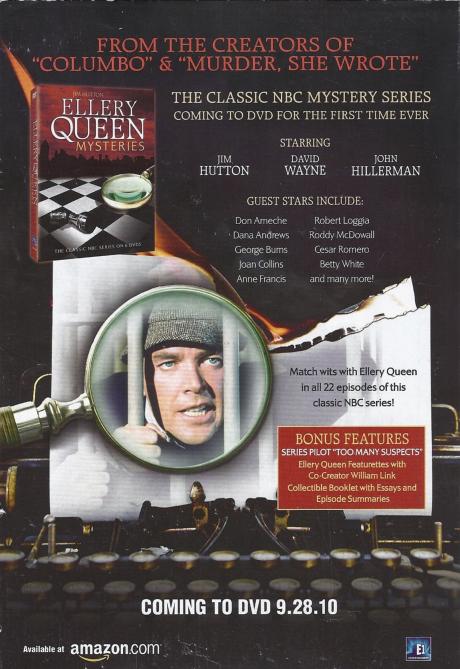

This week the December edition of Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine hit my mail box on the same day that the temperature in Washington, D.C., spiked to 90 degrees. We subscribers have long since become accustomed to these monthly episodes of time warp dictated by the publishing world’s conclusion that an “old” magazine will not sell on the news stands. But while the front cover of EQMM, as usual, defied the season in which it arrived, the back cover was completely timely. It announces in a full color spread that on September 28, 2010, NBC’s 1975 Ellery Queen series will be released in a six DVD set, containing all 22 original episodes, the two hour pilot, and an interview with William Link, who, along with his long-time writing partner the late Richard Levinson, created this one-year television gem.

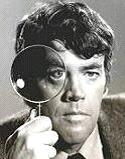

Some of you who have read my sporadic contributions to Criminal Brief may remember that it was just a little over a year ago that I offered up a piece on the NBC Ellery Queen series. That ode to the series accompanied the publication in EQMM of my Ellery Queen pastiche “The Mad Hatter’s Riddle”, EQMM March/April 2009, which featured Ellery as a consultant to the series and takes place during the filming of “The Adventure of the Mad Tea Party”. That episode, originally aired on October 30, 1975, was the only episode of the series (aside from the two hour pilot) that was based on an Ellery Queen story, the classic 1935 short story of the same name. “The Adventure of the Mad Tea Party” has been heralded by Ellery Queen fans and mystery critics alike as probably the finest filmed version of an Ellery Queen work, but this is not to disparage the other episodes of the NBC series. They are uniformly fine—tight writing, clever plots, nice acting, and a wonderful theme by Elmer Bernstein (The sheet music is on my piano as I type!) I have always loved the series, but little did I suspect one year ago when I wrote that last Criminal Brief piece that 2010 would bring forth remastered DVDs of this wonderful portrayal of Ellery.

Some of you who have read my sporadic contributions to Criminal Brief may remember that it was just a little over a year ago that I offered up a piece on the NBC Ellery Queen series. That ode to the series accompanied the publication in EQMM of my Ellery Queen pastiche “The Mad Hatter’s Riddle”, EQMM March/April 2009, which featured Ellery as a consultant to the series and takes place during the filming of “The Adventure of the Mad Tea Party”. That episode, originally aired on October 30, 1975, was the only episode of the series (aside from the two hour pilot) that was based on an Ellery Queen story, the classic 1935 short story of the same name. “The Adventure of the Mad Tea Party” has been heralded by Ellery Queen fans and mystery critics alike as probably the finest filmed version of an Ellery Queen work, but this is not to disparage the other episodes of the NBC series. They are uniformly fine—tight writing, clever plots, nice acting, and a wonderful theme by Elmer Bernstein (The sheet music is on my piano as I type!) I have always loved the series, but little did I suspect one year ago when I wrote that last Criminal Brief piece that 2010 would bring forth remastered DVDs of this wonderful portrayal of Ellery.

So it seems to me this event is a cause for some reflection and, perhaps, a bit of nostalgia. It’s been a long 35 years since we last encountered Mr. Hutton’s portrayal of Ellery Queen.

Television (and the movies, for that matter) fretted a long time trying to get Ellery right. The movie attempts of the 1930s and 1940s are basically unwatchable, portraying Ellery comically as a slap-stick blunderer. As my friend and sometimes collaborator Kurt Sercu, proprietor of “Ellery Queen, a Website on Deduction” has observed, “None of the films in the series is really worthwhile, a distinct disappointment to the mystery fans who came to regard the Ellery Queen stories as top-grade in the mystery genre.”

Early television attempts to bring Ellery and the Inspector to the small screen on the Dumont network and ABC were more successful, but it took Levinson and Link, long-time EQ fans, to finally get it right. And even they took two tries.

I pause here to note what is already evident to those who have read my few contributions to this site and my fewer-still published short stories. I am an Ellery Queen fan. My fiction successes thus far have been works that feature Ellery Queen. Thankfully we have a name for these—pastiches. (It sounds so much better than “fan fiction.”) I did not come to this affection for the works of Queen late in life; I’ve been a fan since my early teens. So it was with great expectation in November, 1971, when I was a senior in college, that I tuned in to the first attempt by NBC to bring Mr. Queen to the small screen. It should have been a dead give-away that trouble was brewing, however. Even though the pilot had been announced as a Levinson and Link production, the credits indicated that it had been written by “Ted Leighton.” It was not until years later that Messrs. Levinson and Link admitted that they had been so under-whelmed by NBC’s re-working of their script, originally based on the EQ novel Cat of Many Tails, that they had insisted the project could only go forward under the banner of a non-existent script writer. Hence the birth (and death) of Mr. Leighton.

It is difficult to imagine a worse Ellery Queen than Peter Lawford, who portrayed Ellery in that pilot as a mod Brit sporting a constant Nehru jacket. Harry Morgan (earlier of Pete and Gladys, later of M*A*S*H) was more credible as the Inspector, but since he was only seven years older than Mr. Lawford he had to be cast not as Ellery’s father but as his “American uncle.” The script took the basic and rather dark premise of the book, referenced it once as a throw-away line, and otherwise abandoned it. The totality of the result was terrible. Thankfully this sorry exercise never made it to its intended berth as one of the recurring series under NBC’s Sunday Night Mystery umbrella. (It was MacMillan and Wife, starring Rock Hudson and Susan St. James, that instead got the nod.)

After that debacle in 1971 I figured that would be it for Ellery on television.

But Link and Levinson were determined, unbowed and undaunted. It was four years later, when I was a second year law student, that their second attempt was screened in March of 1975 as a two hour NBC movie. This pilot for the series that followed was based on Queen’s The Fourth Side of the Triangle, published in 1965. (That novel, while edited by Manfred Lee, was written during his famous “writer’s bloc” era, and in fact, was “ghosted’ by science fiction writer Avram Davidson from a 71-page detailed outline by Frederic Dannay.) The pilot re-set the story in 1947, casting Jim Hutton as Ellery and David Wayne as the Inspector. The pilot also removed an awkward element from the novel—there Ellery, Mycroft Holmes-like, solves the mystery largely from a hospital bed. In the NBC version, Ellery is present front and center for all of the action.

But Link and Levinson were determined, unbowed and undaunted. It was four years later, when I was a second year law student, that their second attempt was screened in March of 1975 as a two hour NBC movie. This pilot for the series that followed was based on Queen’s The Fourth Side of the Triangle, published in 1965. (That novel, while edited by Manfred Lee, was written during his famous “writer’s bloc” era, and in fact, was “ghosted’ by science fiction writer Avram Davidson from a 71-page detailed outline by Frederic Dannay.) The pilot re-set the story in 1947, casting Jim Hutton as Ellery and David Wayne as the Inspector. The pilot also removed an awkward element from the novel—there Ellery, Mycroft Holmes-like, solves the mystery largely from a hospital bed. In the NBC version, Ellery is present front and center for all of the action.

Joyously, NBC responded to the decent ratings the pilot garnered by picking up the series and giving it a then-coveted berth at 9:00 on Thursday nights.

The series opened on September 11, 1975, with “The Adventure of Auld Lang Syne”. This may not have been the wisest gambit since Ellery has less of a rôle in the episode than in subsequent ones. In fact, production notes indicate that the first episode filmed was likely the previously-discussed “Adventure of the Mad Tea Party”, an episode that was not aired until October 30. In any event, the series gained good reviews but attracted a mediocre audience. Its ratings climbed, however, and in October NBC renewed it for a full season. But then, in an ultimately disastrous decision, the network moved the show to Sunday nights at 8:00. There the series was scheduled opposite The Six Million Dollar Man on ABC (a perennial top-ten show at the time) and (unbelievably) also opposite CBS’s revamped Sonny and Cher show, which to much anticipation, paired the then newly-divorced singing duo in a remake of their previous top 10 series.

NBC had previously tested the Sunday night berth with one Ellery Queen episode, titled, perhaps presciently, “The Adventure of Miss Aggie’s Farewwell Performance”, on October 19th. The regular Sunday night episodes began on January 4, 1976 with “The Adventure of the Black Falcon”, which, opposite a re-run of Six Million Dollar Man, scored number 11 in the weekly Nielsen ratings. This proved, however, to be the high water mark for Ellery Queen. One week later The Six Million Dollar Man offered a new episode, Sonny and Cher premiered, and Ellery Queen’s ratings sank to unreported depths. At the end of 1976, after 22 episodes, the series was cancelled.

So, other than luck of the draw, why did this series, one of the most nimbly executed whodunits ever, fail to find an audience? As I noted in my article last year, the belief of Levinson and Link was that the show was simply too well done, too cerebral for its intended audience. It demanded a lot if you were intent on watching it over a beer.

In his 2002 article “Confessions of a Mystery Writer”, William Link wrote: “Thinking back, the Queen series was too complicated for its own good. I remember spending an entire afternoon with Dick [Levinson] trying to figure how keys on a keychain would fall into what configuration in one’s pocket when placed there.” When audiences didn’t respond the lesson was learned: “[o]ur failure with Ellery Queen was our template” for future efforts, Levinson observed. “We deliberately made the clues on Murder She Wrote easier to decipher, including a very guessable murderer now and then. Part of our psychology was to reward the focused viewers because they might then be motivated to return the following week. Another unexpressed reason was that it was far easier to come up with facile clues than sweating bullets over keys in a pocket…. The upshot was that Murder She Wrote thrived for 12 seasons, Ellery Queen [only] one.”

In short, the Queen show simply refused to write to wide denominator. It played to a higher appreciation level.

And now, after so long, the series is back. How long has it been? Well, speaking personally, the college student who watched Mr. Lawford in 1971, and the law student who faithfully watched Mr. Hutton every week, is now retired.

While I have attributed the memories set forth above to my personal experience with the series, my recommendation that fans of this site purchase the new DVD set is not based solely on 35-year-old memories. In my family room I have a set of DVDs with all episodes of the series, purchased some years back on eBay and recorded from the A&E network re-broadcasts of approximately 15 years ago. My copies are grainy and have bad edits; in some instances the commercials were not even removed. Some of the introductions are missing as well. But I can promise you that even in that sorry state all of the episodes are gems—at times they outshine Queen’s own stories in cleverness and fair-play. And the production values hold up amazingly well in 2010 (which should be even more the case with re-mastered originals instead of the grainy recordings I and everyone else until now has been relegated to). Somewhat paradoxically, even though the series is set in 1947 it is not at all dated. In other words it doesn’t look like a 1970s series since it was never intended to be a 1970s series.

It is interesting that while the intricate and intelligent whodunits that comprise the NBC series were too much for audience demographics in 1975, when all television was comprised of three networks and PBS, they likely will play very differently today. Unlike the 1970s, multiple cable outlets and affordable DVDs tempt producers to play to niche markets rather than abandon them. I hope that is the case with The Ellery Queen Mysteries, but I know that it will, in any event, be the case in the niche market that is my family room.

The Ellery Queen Mysteries should be in video stores tomorrow. The set is also available for on-line ordering from Amazon.com. Welcome back, Mr. Queen!

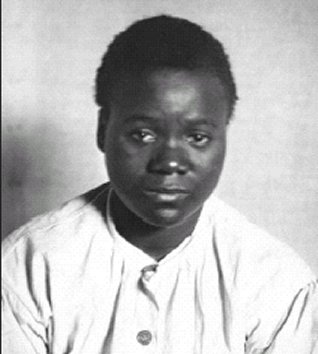

used to prop open bedroom windows. The girl struck Belote’s forehead and the woman collapsed. To stem Belote’s shrieking, Gennie Christian stuffed a tea towel in her mouth, not realizing she forced the woman’s tongue down her throat. The girl fled the house, taking the woman’s purse.

used to prop open bedroom windows. The girl struck Belote’s forehead and the woman collapsed. To stem Belote’s shrieking, Gennie Christian stuffed a tea towel in her mouth, not realizing she forced the woman’s tongue down her throat. The girl fled the house, taking the woman’s purse.